Ballast was – and is – critical to the safety of all ships, with various materials used, including shingle, sand, stone and iron bars. Ballast needed securing to prevent it shifting and causing a catastrophe. Many vessels sailed ‘in ballast’ when they had no cargo. The provision of ballast was a substantial industry worldwide, and in past times much of the loading and unloading was done by hand.

Although individual ships may have been expertly designed, skilfully constructed and many even given the highest rating by Lloyd’s Register, something as basic as ballast, a temporary and constantly changing load, was vital to a vessel’s survival. The word ‘ballast’ first appears in the English language in the late 15th century to denote any heavy material placed in the bottom of a vessel. This was crucial for the safety of ships, because ballast lowered the centre of gravity (the point where everything is balanced), improving stability and preventing the vessel from toppling over. 1

William Falconer was a Scottish poet, mariner and author of An Universal Dictionary of the Marine. First published in 1769, in it he defined ballast as ‘a certain portion of stone, iron, gravel, or such like materials, deposited in a ship’s hold, when she has either no cargo, or too little to bring her sufficiently low in the water. It is used to counter-balance the effort of the wind upon the masts, and give the ship a proper stability, that she may be able to carry sail without danger of over-turning.’2 Merchant ships that carried a cargo like coal or grain rarely carried ballast, but a great deal could be necessary with a light cargo, such as tea, tobacco or wool, and the amount needed was a matter of trial and error. At the destination port the cargo was discharged, and any ballast required was loaded in readiness for the next cargo. If no cargo was available at that port, enough ballast had to be loaded before heading home or to another port for a cargo.

Shingle ballast of large pebbles

Ballast of sand and small stones

Ballast of silt, sand and stones

Some vessels started off without any cargo, a loss-making voyage, perhaps to Australia for grain, Chile for nitrates or Peru for guano, in which case they needed ballast for the initial outbound journey. The range of materials included gravel, shingle, sand, mud, stone, chalk, demolition rubble, industrial waste such as slag, bricks, tiles and iron pigs. Vessels described as ‘in ballast’ had ballast to ensure stability, but no commercial cargo, although the ballast might be a low-value cargo such as salt, chalk, coal, bricks or iron, which could be offered for sale on arrival. With shipwrecks it is not always possible to distinguish between ballast and the cargo. In April 1656 the Dutch East India Company ship Vergulde Draeck struck a reef on the coast of Western Australia, and underwater excavations have discovered about 8,000 bricks, often referred to as ‘ballast bricks’. They were actually intended for sale, as Company records show that thousands of bricks were transported by several of their vessels, including 26,000 on the Vergulde Draeck’s first voyage in 1653. 3

Sailing in ballast was not ideal from an economic or a safety point of view, but it was often done. Ships arriving or departing in ballast were routinely recorded in newspapers, like those mentioned by the Hull Daily Mail as arriving on 15 October 1925 at the Yorkshire port of Goole on the River Ouse:

Greenawn s, Cherbourg, ballast

Yokefleet s, Portsmouth, ballast

Kempton s, London, ballast

Horn s, Southampton, ballast

Syria s, Boulogne, general (cargo)

Liberty s, Ghent, general (cargo)

Rawcliffe s, Amsterdam, general (cargo)

Broomfleet s, Cowes, ballast

Rye s, Antwerp, general (cargo).4

On the next day eight more ships arrived, all in ballast, and although these Goole vessels had made only short journeys, many other ships routinely sailed in ballast on trans-Atlantic and trans-Pacific voyages.

All over the seafaring world ballast was essential, and the ideal ballast was inexpensive, heavy and easy to stow and secure. In order to avoid blocking pumps and spoiling cargoes, the preferred ballast was dry and solid, like stone. From the mid-19th century water ballast systems were increasingly used as well, so the term ‘solid ballast’ came to describe all non-liquid forms of ballast. The ballast had to be purchased, and because most destination ports charged for unloading it, some captains took risks in order to reduce costs.5

Warships needed to be well ballasted since they carried a great deal of weight on gundecks, with their cannons and shot. Scrap ordnance, shot and shells were traditionally reused as ballast, but from the early 18th century pig iron became more common, cast specifically for the Royal Navy into bars known as pigs that usually measured 3 feet x 6 inches x 6 inches, though smaller versions were also produced. Referred to as kentledge ballast, many tons of these iron bars were loaded and stacked, before being covered with shingle and gravel ballast. Any iron pigs carried on merchant ships were generally curved and intended as trade items. 6

For almost three centuries from 1594 Trinity House had the rights of ballastage on the River Thames below London Bridge, with a monopoly on obtaining and selling ballast, and the profits went into establishing and maintaining buoys, beacons and lights. Colliers constantly brought coal to London from Newcastle and Sunderland, but without return cargoes they sailed back empty, apart from ballast for stability. The ballast was primarily sand and gravel dredged from the Thames, which kept the waterway clear, and it was deposited in Trinity House lighters and taken to colliers and other merchant ships for ballast-heavers to shift. Vessels could load other types of ballast, such as bricks and even London’s refuse and dung. 7

Trinity House and the Ballast Office

Part of Trinity House, rebuilt after the Second World War

This wing with the commemorative plaque is on the site of the old Ballast Office.

Trinity House commemorative plaque with the coat of arms

Henry Mayhew, a journalist and social reformer, visited various haunts along the Thames in 1849–50 while investigating the labouring classes. He reported that on average each collier needed 80 tons of ballast, which was shifted from the lighters into the colliers by gangs of four ballast-heavers. ‘According to the returns of the Trinity House,’ he said, ‘there were 615,619 tons of ballast put on board 11,234 ships in the year 1848. The ballast-heavers are paid at the rate of 6d. per ton for shovelling the ballast out of the Trinity Company’s lighters into the holds of the vessels.’ He was outraged that most were hired out by publicans, who forced them to drink to excess at their beerhouses or else be refused work.8 One foggy night he watched a gang ballasting a collier in the Pool of London:

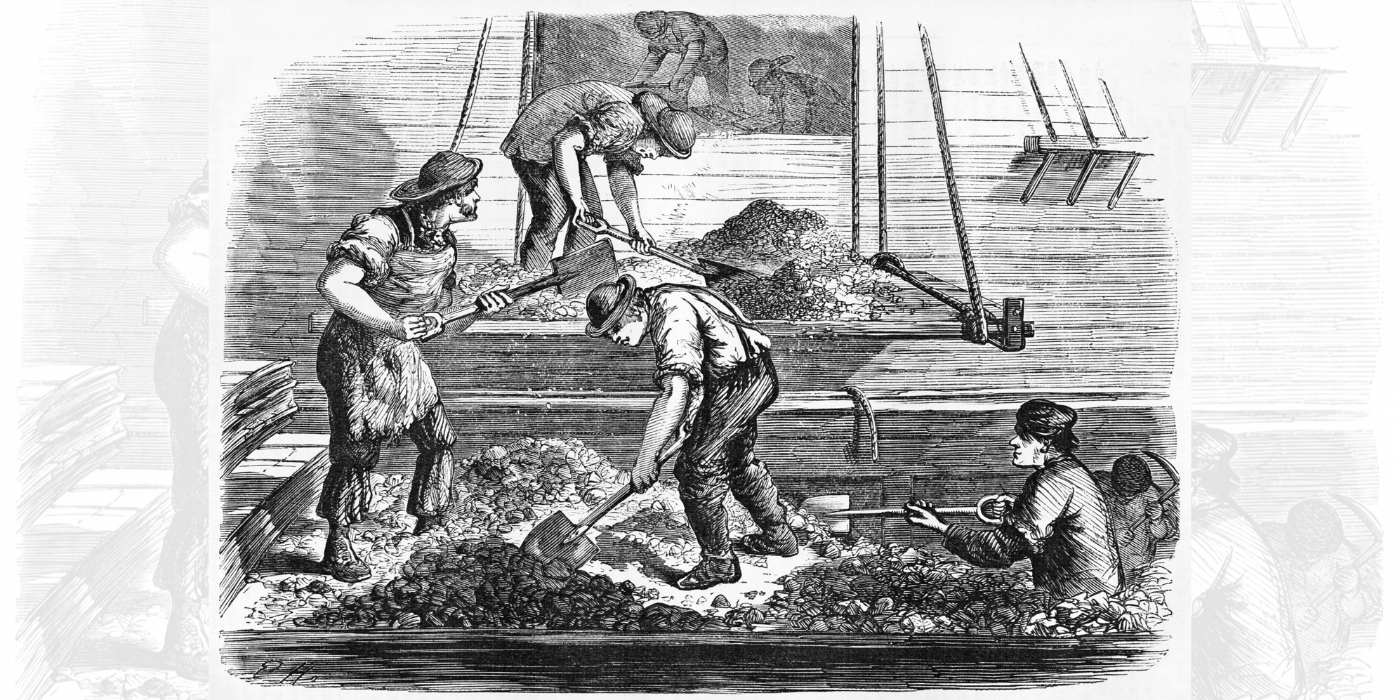

The ballast-heavers had established themselves alongside a collier to be filled with 43 tons of ballast ... Two men stood in the gravel (the ballast) in the lighter; the other two stood on ‘a stage,’ as it is called, which is but a boarding placed on the partition beams of the lighter. The men on this stage, cold as the night was, threw off their jackets, and worked in their shirts, their labour being not merely hard, but rapid. As one man struck his shovel into the ballast thrown upon the stage, the other hove his shovelful through a small port-hole in the vessel’s side, so that the work went on as continuously and as quickly as the circumstances could possibly admit. Rarely was a word spoken. 9

Colliers in the Pool of London

Ballast-heavers at work in the Pool of London

The work was relentless, and Mayhew calculated that the gang moved at least 10 tons an hour:

The throwing of the ballast through the port-hole was done with a nice precision ... The men pitched the stuff through most dexterously. The port-hole might be six feet above the stage from which they hove the ballast; the men in the lighter have an average heave of six feet on to the stage. The two men on the stage and the two on the lighter fill and discharge their shovels twelve times in a minute; that is, one shovelful is shot by each man every alternate five seconds ... The men work with the help of large lanterns, being employed mostly by night. 10

In 1769 Falconer commented: ‘The knowledge of ballasting a ship with propriety is certainly an article that deserves the attention of the skilful mariner.’11 The ballast had to be carefully trimmed, distributing the weight fore-and-aft, and Mayhew observed that the crew of the collier did that work. It also had to be properly secured, so as not to shift and endanger the vessel. In 1938 Thomas Wells was an apprentice on board the Passat, a four-masted steel barque destined for Australia. He noted that two of the vessel’s four holds were filled with 2,000 tons of sand and rock ballast, and after being covered with planking (dunnage), this wooden flooring and the ballast were held in place with 90-foot lengths of chain. ‘If her ballast is properly stowed,’ he wrote, ‘a vessel should be able to heel over until her main yard touches the water without having the ballast shift’. Shortly afterwards, they experienced a hurricane off the coast of Scotland, and he was relieved to write: ‘The Passat dips her main yard in the water ... The ballast holds.’ 12

The four-masted Passat

Sailing ships in the Berbice River, Guyana, in 1860

Some ballast like sand proved challenging, as it shifted easily, but mud was worse. In 1859, when 14 years old, Harry Hine joined the crew of the barque Flying Fish on her maiden voyage from Gravesend to Berbice in South America, known today as Guyana. 13 Here they went up the Berbice River to deliver their cargo of bricks, before loading with ballast so as to sail safely to Barbados. ‘In later voyages I ballasted with stone and many other things,’ he said, ‘but only this once with mud! There was nothing else available or so cheap.’ Two local men stood in the waist of the ship and hauled blue clay from the bottom of the river with long-handled iron scoops, filling the hold with liquid mud. Hine described their perilous situation: ‘During the passage to Barbadoes, as we pumped this out, the vessel became so top heavy and cranky that we were compelled to shorten sail and finally to single reef the topsails to prevent her turning turtle.’ 14

Ballast was unloaded from vessels by hand, which was arduous, even when assisted by donkey engines, horses or steam-operated cranes. Purpose-built quays were established at innumerable locations, and here and there the word ‘ballast’ lingers in place-names. One example of a quay was at Leith in Scotland, where a newspaper advertisement in April 1777 invited bids for the building of a new ballast quay, ‘either of ashlar or with timber filled up with stones to the high water mark, in the same way that the north end of the Ballast Quay is at present ... The Quay is to be eleven feet thick at the base, and eight at the top’. 15 Ballast discharged at ports, often from ‘in ballast’ vessels, might be loaded into other ships, sold to the construction trade or else shifted further away from the quay.

In his history of Newcastle-upon-Tyne, published in 1649, William Grey said that the returning colliers had to offload their ballast near ‘the Ballist Hill, where women upon their heads carried ballist, which was taken forth of small ships which came empty for coales; which place was the first ballist shore out of the town’. Situated at Ouseburn, on the east side of Newcastle, this became a huge Ballast Hill and was used for thousands of nonconformist and pauper burials. Anne Forster was one of the ballast women, and when she died in February 1777 at the unlikely age of 123, it was reported: ‘In her early years, she assisted in carrying ballast from lighters in the river to the Ballast-hills, now a public depository for the dead.’ 16 Ballast management at Newcastle-upon-Tyne was an enormous civic undertaking, and in 1617 regulations to control and protect the river stipulated that ‘all the ballast shores in the river of Tyne to be constantly kept in good repair, otherwise a hundred thousand tons of ballast will fall into the river’.17 Over the decades, the number of ballast shores increased on both sides of the lower Tyne, where the colliers discharged their load directly or into ballast keels (lighters).

Looking towards the mouth of the River Tyne

The River Tyne looking towards Newcastle

Ballast was often discarded overboard, but such unregulated disposal could lead to rivers and ports becoming blocked. Arriving at the Chincha Islands of Peru in 1853, one passenger noted: ‘The first duty of the crew after the ship’s arrival is to discharge the extra ballast, and as the captains have no dread of port-officers or harbour-masters, the sand or stone is quietly tossed over the side, until there is barely sufficient left in the hold to keep the vessel on an even keel.’ 18 Many ports had ballast masters who controlled the disposal of ballast at quays and offshore ballast dumping grounds, and there were penalties for illicit dumping. The American lawyer Richard Henry Dana wrote a bestselling memoir about his experiences over two years as a seaman. In March 1836 he was on board the three-masted Alert when they came into San Diego harbour, their last port of call before returning to Boston via Cape Horn. One task was to dispose of much of the ballast to make more room for the cargo of about 40,000 hides that were waiting to be loaded:

A regulation of the port forbids any ballast to be thrown overboard; accordingly, our long-boat was ... brought alongside the gang-way, but where one tub-full went into the boat, twenty went overboard. This is done by every vessel, for the ballast can make but little difference in the channel, and it saves more than a week of labor, which would be spent in loading the boats, rowing them to the point, and unloading them. When any people from the presidio were on board, the boat was hauled up and the ballast thrown in; but when the coast was clear, she was dropped astern again, and the ballast fell overboard. This is one of those petty frauds which every vessel practises in ports of inferior foreign nations.19

In a time-consuming and costly process, sailing vessels at the grain ports of Australia went to ‘ballast grounds’ further out at sea to unload some of their ballast, then back to the port for grain, then another trip to the ballast grounds to get rid of the remaining ballast, before loading the rest of the grain. 20 On reaching Australia at the end of 1938, the Passat anchored at the ballast grounds 8 miles from Port Lincoln. The crew shovelled half the ballast from the two holds into substantial baskets, which were hoisted up with a donkey engine and the contents tipped over the side, joining thousands of tons of European soil and construction waste from countless other vessels. The Passat next sailed to Port Lincoln, and Thomas Wells said that although the vessel was relatively stable, she was now high out of the water, making the steering precarious. Bags of grain were loaded into the two empty holds, and then they sailed back to the ballast grounds to discharge the remaining ballast and clean out those two holds. They then returned for the final load of grain – their homeward journey to Falmouth and Belfast needed no ballast. 21

Unloading ballast by hand

The four-masted Passat at Port Victoria, Australia

Insufficient ballast, too much ballast or shifting ballast could lead to disaster, and removing ballast prematurely was also risky. During a Select Committee of the House of Lords in 1903, many witnesses gave damning evidence about common practices, including Captain Alexander Wood, a nautical assessor, who summarised his thoughts:

Formerly when ships were under private ownership the master was frequently the largest owner in the vessel, had a large influence in the management, and was almost allowed a free hand in all matters relating to the navigation. At that time the struggle for existence, through competition, was not so intense, and in ballasting his ship a master could always act on the side of safety. In approaching the limit of safety he knew that whatever danger he incurred for his crew he himself would share ... All this, however, is changed under the modern development of shipping into joint stock companies. The master has simply become an inferior kind of servant to do as he is bidden, and ask no questions.22

The same judgement was expressed only a few years earlier by a Liverpool newspaper, critical of ship losses and the lack of attention paid to ballasting: ‘Whether negligence, or ignorance, is at the bottom of these losses is difficult to determine. The master of a vessel is on the spot, her owners are probably thousands of miles away, and the responsibility for her ballasting must rest solely with him.’ 23 Profit too often came before the safety of the vessel, the cargo and the crew.

See part 2 of the Ballast story here.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the Lloyd’s Register Group or Lloyd’s Register Foundation.

The Passat museum ship at Travemünde, Germany: https://museumships.us/germany/passat

The history of Trinity House: https://www.trinityhouse.co.uk/about-us/history-of-trinity-house

San Diego, Richard Henry Dana and ballast: https://sandiegohistory.org/archives/books/bells/ch14/

The Ballast Hills burial ground and park at Ouseburn: https://fabulousnorth.com/ballast-hills-burial-ground/

Footnotes

-

1

See p 15 of P W King 1995 ‘Iron Ballast for the Georgian Navy and its Producers’ The Mariner’s Mirror 81, pp 15–20.

-

2

William Falconer 1769 An Universal Dictionary of the Marine (London: T. Cadell), unpaginated. Falconer lived 1732–70.

-

3

Jeremy N Green 1977 The Loss of the Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie Jacht Vergulde Draeck, Western Australia 1656 (Oxford: British Archaeological Reports Supplementary Series 36 part i), pp 169–72.

-

4

<i>Hull Daily Mail</i> 16 October 1925, p 12

-

5

Martin Lee 2000 ‘The ballasting of the twentieth-century deep water square rigger’ The Mariner’s Mirror 86, pp 186–96, in particular pp 188–92.

-

6

King 1995; Emmanuel Nantet and Guillaume Martins 2023 ‘From Old Cannon to Iron Pigs: The introduction of Kentledge ballast in the early modern French navy’ The Mariner’s Mirror 109, pp 401–8. Pig iron ingots were originally called ‘pigs’, because of the way they were cast, resembling a litter of piglets.

-

7

G G Harris 1969 The Trinity House of Deptford 1514–1660 (London: The Athlone Press), pp 127–52; Andrew Adams and Richard Woodman 2013 Light Upon the Waters: The History of Trinity House 1514–2014 (London: The Corporation of Trinity House), especially Chapter 6; Cori Convertito-Farrar and Kenneth Cozens 2012 ‘The Operations of the Trinity House Ballast Office in the late Eighteenth Century’ Proceedings of the Fourth Symposium on Shipbuilding and Ships in the Thames; The Morning Chronicle 1 January 1850, p 5 (for Mayhew).

-

8

The Morning Chronicle 1 January 1850, pp 4–5; and 4 January 1850, pp 4–5.

-

9

The Morning Chronicle 4 January 1850, p 5.

-

10

The Morning Chronicle 4 January 1850, p 5.

-

11

Falconer 1769, unpaginated.

-

12

Thomas W Wells 1994 ‘Ballast and Cargo Handling On Board the Bark Passat’ The Log of Mystic Seaport 45, pp 110–15; Lee 2000, p 195.

-

13

The Flying Fish, 221 tons, was built under special survey in 1858 and rated ✠A1 by Lloyd’s Register. See Lloyd’s Register of British and Foreign Shipping, from 1st July, 1859, to the 30th June, 1860 (London, 1859)

-

14

Harry Hine 1935–6 ‘The Anchor’s Weighed – 1859’ The Seagoer 3 no. 2, pp 103–22. Hine lived 1845–1941.

-

15

Caledonian Mercury 21 April 1777, p 4.

-

16

William Grey 1649 Chorographia, or a Survey of Newcastle upon Tine (p 40 of the 1818 edition published by Emerson Charnley, Newcastle); John Sykes 1833 Local Records; or Historical Register of Remarkable Events, in Two Volumes, vol. 1 (Newcastle: John Sykes), pp 309, 339.

-

17

Richard Welford (ed) 1887 History of Newcastle and Gateshead vol. III., sixteenth & seventeenth centuries (London: Walter Scott), p 217; Peter D Wright 2020 ‘The Ballast Trade: An Economic Driver in Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-century Newcastle upon Tyne’ Northern History 57, pp 101–19.

-

18

See p 434 of ‘A Visit to a Guano Island’ The Leisure Hour 7 July 1853, pp 433–6.

-

19

Richard Henry Dana Jr 1840 Two Years Before the Mast: A Personal Narrative of Life at Sea (New York: Harper & Brothers), pp 323–5. The Alert, 398 tons and 2 decks, was built at Boston in 1828. El Presidio Real de San Diego had been a military base and is now a National Historic Landmark.

-

20

Lee 2000, p 192.

-

21

Wells 1994, pp 113–15. For photographs of filling baskets with ballast and tipping them overboard on board the Moshulu in 1939, see Eric Newby 1999 Learning the Ropes: An Apprentice in the Last of the Windjammers (London: John Murray), pp 102–3.

-

22

Report from the Select Committee of the House of Lords on Light Load Line; together with the proceedings of the committee, minutes of evidence, and appendix 1903 (London: HMSO), paragraph 282.

-

23

Liverpool Journal of Commerce 29 January 1897, p 4.