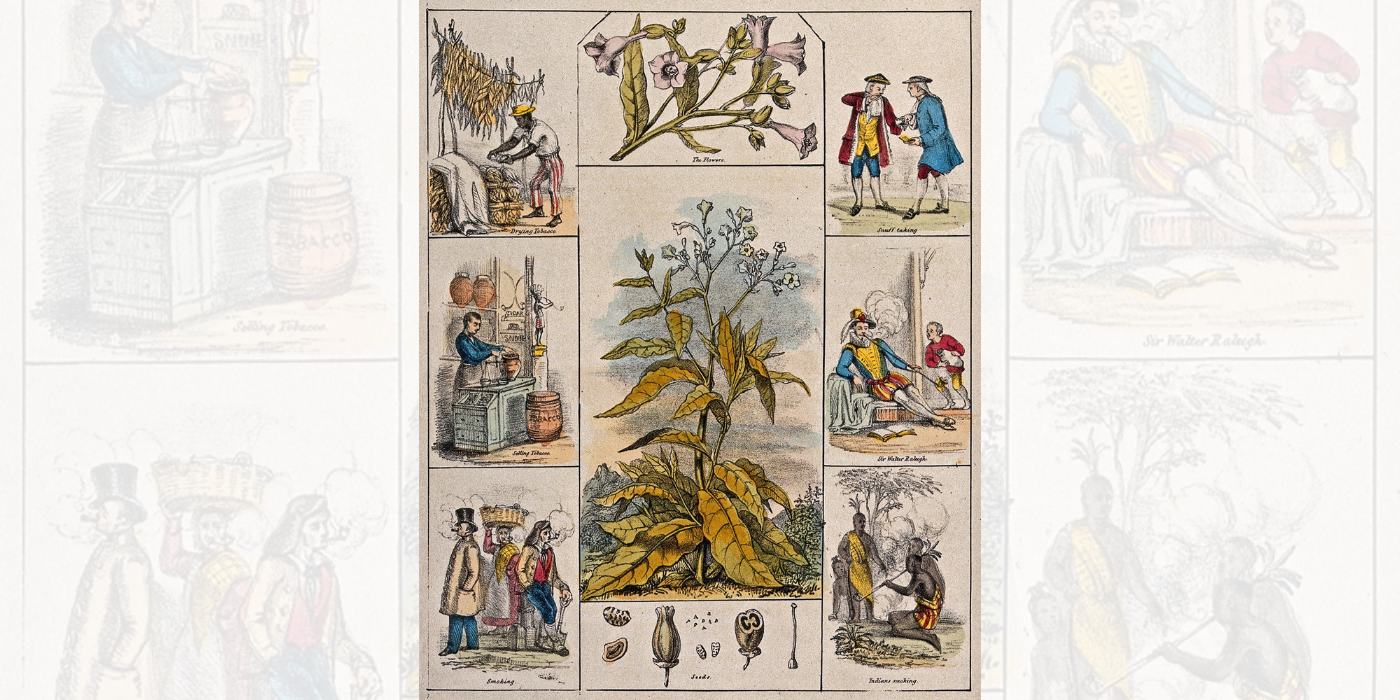

Tobacco was originally used as a medicinal herb, but from the late 16th century smoking with pipes was introduced to England. A substantial industry developed for manufacturing clay pipes, which were exported by sea worldwide and are found in shipwrecks. Smoking became completely acceptable behaviour, even aboard wooden vessels, and for four centuries seamen and passengers using pipes, cigarettes and matches were a significant cause of maritime fires and disasters. This was a huge risk to safety on board.

For thousands of years before Christopher Columbus discovered the New World in 1492, tobacco had been cultivated in the Americas, where it was smoked (inhaling the smoke of burning tobacco), snuffed (inhaling powdered dried tobacco leaves), chewed, swallowed in liquids and applied as poultices. The main functions of tobacco were for religious rituals, medicines and trade. As ships increasingly plied the Atlantic, sailors encountered the native populations and adopted their habit of smoking. 1

From 1559 Jean Nicot was the French ambassador at Lisbon in Portugal, where he obtained cuttings to grow tobacco in his embassy’s gardens and then tried out its reputed medicinal properties. One of his claims was the cure of a man with a tumour by applying an ointment made from tobacco leaves. He subsequently gave tobacco leaves and seeds to the French queen, Catherine de Medici, and also recommended making snuff from crushed leaves to prevent and cure all kinds of afflictions. Tobacco as a herbal remedy was rapidly adopted across Europe in the late 16th century, and the name nicotiana tabacum was given to the tobacco plant, while the active ingredient was called nicotine.

In 1595 the first work in English to discuss the apparent benefits of tobacco was published by Anthony Chute, who included the evidence of Nicot and others on the Continent. Chute also promoted tobacco as a protection against plague: ‘I thinke man hath not known an excellenter preservative against the late dangerous infection, than this, and if any one who made use of it in good order, hath died of the infection, I am truely resolved, that for that one which died, it hath saved threescore.’2 He also mentioned smoking tobacco, which had been widely adopted in England, for pleasure rather than as a herbal remedy. Over the centuries there would be arguments between those proclaiming tobacco’s health benefits and those warning of the harm.

Early tobacco smoking with a clay pipe

Tobacco plant

Sea captains such as Sir Walter Ralegh, Sir Francis Drake and Sir John Hawkins are variously cited as having introduced smoking, though it was more likely their seamen, as stated in the ‘Bristol Annal’ manuscript for 1586: ‘Tobacco first brought into England by the mariners of Sir Francis Drake.’ 3 Smoking was known even earlier, and in the 1570s William Harrison, a clergyman and historian, wrote about a pipe or pipe-like device in his ‘The great English chronology’ manuscript: ‘In these daies, the taking-in of the smoke of the Indian herbe called “Tabaco,” by an instrument formed like a little ladell, wherby it passeth from the mouth into the hed & stomach, is gretlie taken-up.’ 4

Paul Hentzner was a German visitor to London in 1598, and he remarked that the English constantly smoked: ‘They have pipes on purpose made of clay, into the farther end of which they put the herb, so dry that it may be rubbed into powder, and putting fire to it, they draw the smoak into their mouths, which they puff out again, through their nostrils, like funnels, along with plenty of phlegm and defluxion from the head.’ 5 White or off-white clay pipes for smoking tobacco were mass produced in moulds, and this industry spread to Europe. Hundreds of thousands of clay pipes were widely transported by sea, packed in barrels, boxes, chests and baskets.6

Clay pipe fragments

Broseley Pipeworks

Making clay pipes

Clay pipes are found on many shipwrecks, though it is not always apparent if they were part of the cargo or personal items of the crew and passengers. The earliest securely dated clay pipe comes from a ship that sank off Alderney in the Channel Islands, probably in November 1592, where a rare pewter pipe was also found similar to one from the wreck of the San Pedro that sank off Bermuda in 1595. 7 Between 1652 and 1656, an unidentified merchant ship, probably Dutch, was wrecked in Monte Cristi Bay on the north coast of Hispaniola, possibly due to an explosion. Known as the ‘Monte Cristi Wreck’ or ‘Pipe Wreck’, the number of clay pipes found was remarkable – around 10,000, of Dutch manufacture.8 In April 1656 the Dutch East India Company ship Vergulde Draeck struck a reef on the coast of Western Australia. The wreck was discovered in 1963, and during an excavation in 1972, numerous clay pipes were recovered, including a box containing 223 unused ones, also of Dutch manufacture. 9

Smoking clay pipes

Smoking clay pipes in 1957

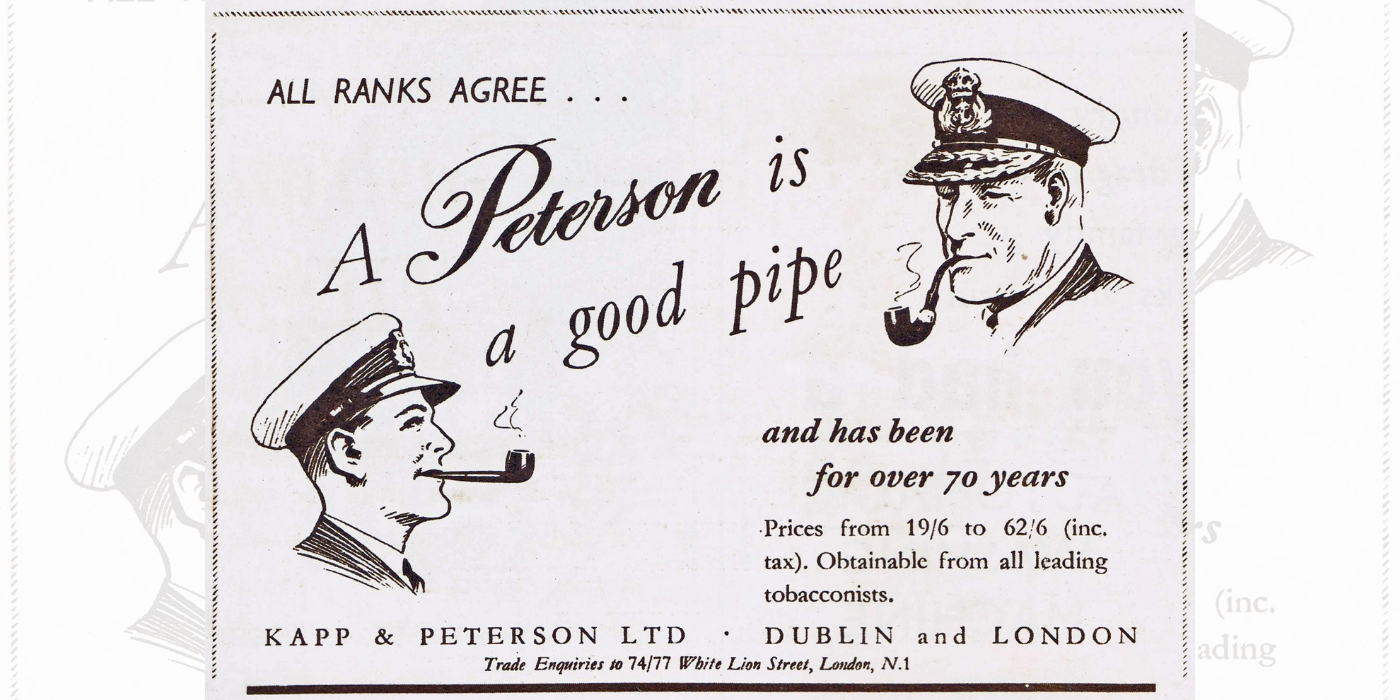

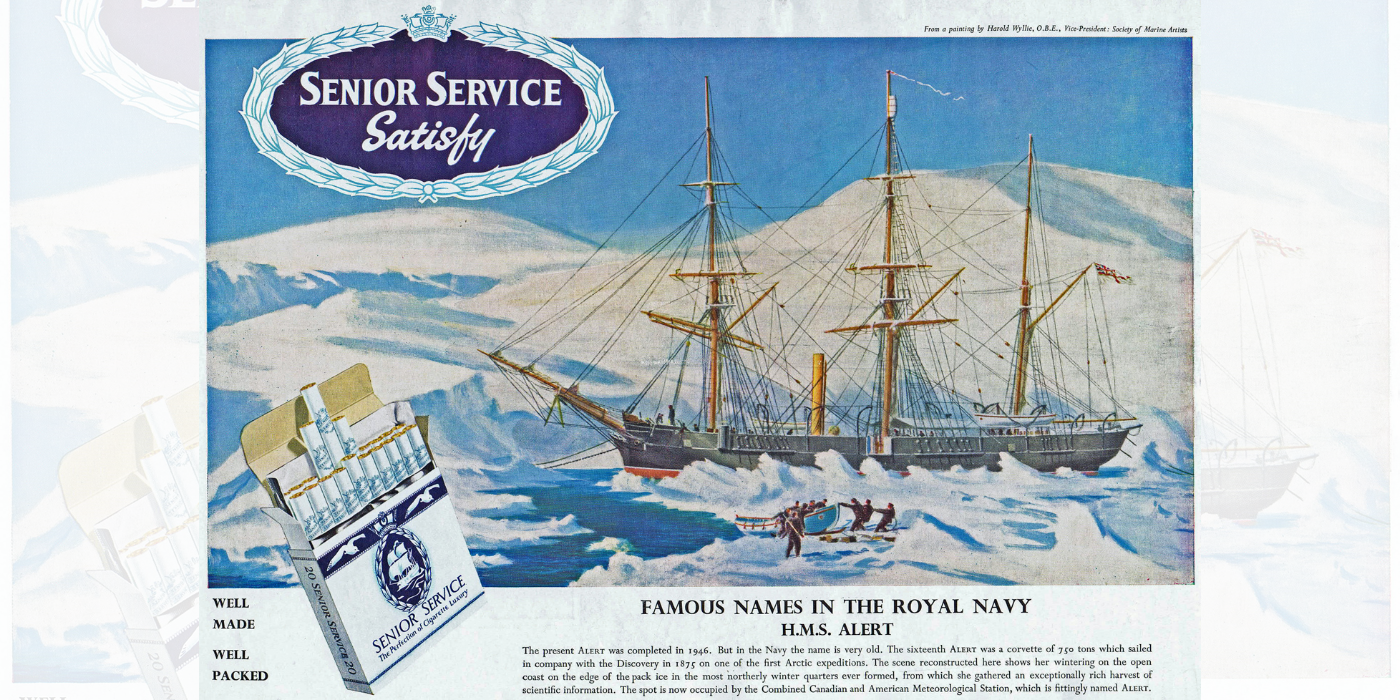

Smoking became so commonplace that it was regarded as normal behaviour, and a substantial industry of smoking and tobacco paraphernalia developed, including pipes, matches, lighters, snuff boxes and spittoons. Pipes of meerschaum (a mineral) were made from the mid-18th century, though briar pipes (of wood) were later predominant. Cigarettes (tobacco in a cylinder of thin paper) were popular from the late 19th century, and advertising for cigarettes and pipe tobacco was frequently linked to the sea and the navy. 10

J H Wood was an apprentice in the four-masted iron barque Rowena, rated A1 by Lloyd’s Register, 11 when in the spring of 1909 she sailed with timber from Vancouver to Falmouth on a passage that took almost six months. He explained that like all ships, they had a large stock of duty-free tobacco, which the crew was able to draw on a Saturday evening: ‘Tobacco at sea, and particularly in sailing ships was a very important commodity, and smoking a much indulged in pastime.’ In addition to smoking, he said that tobacco was used as currency and in gambling, as well as being chewed, particularly at the wheel where smoking was forbidden. During the passage, it was discovered that a deserter at Vancouver had taken some of the tobacco stock, so after rounding the Horn, Captain Cadwalader put everyone on a reduced ration, which turned a happy ship into a discontented one: ‘With the shortage of tobacco, leisure had not the same pleasure and many found it difficult to pass the time away. One man died (true, of natural causes) but some of the crew fully believed that a good smoke would have saved him. Tobacco was indeed the chief thought and conversation.’ The seamen even scoured the timber cargo for bark, which was mixed with other detritus to form a substitute tobacco for smoking, such was their addiction.12

Briar pipes for all ranks

Senior Service cigarettes

For some four centuries, the smoking of tobacco was a prime cause of fires on board ships, especially wooden ones. Candles and lanterns were strictly controlled, and warships generally restricted smoking to the upper deck or round the galley stove, so many seamen chose to chew tobacco instead. 13 If the cause of a fire was not obvious, spontaneous combustion or smoking was considered most likely.

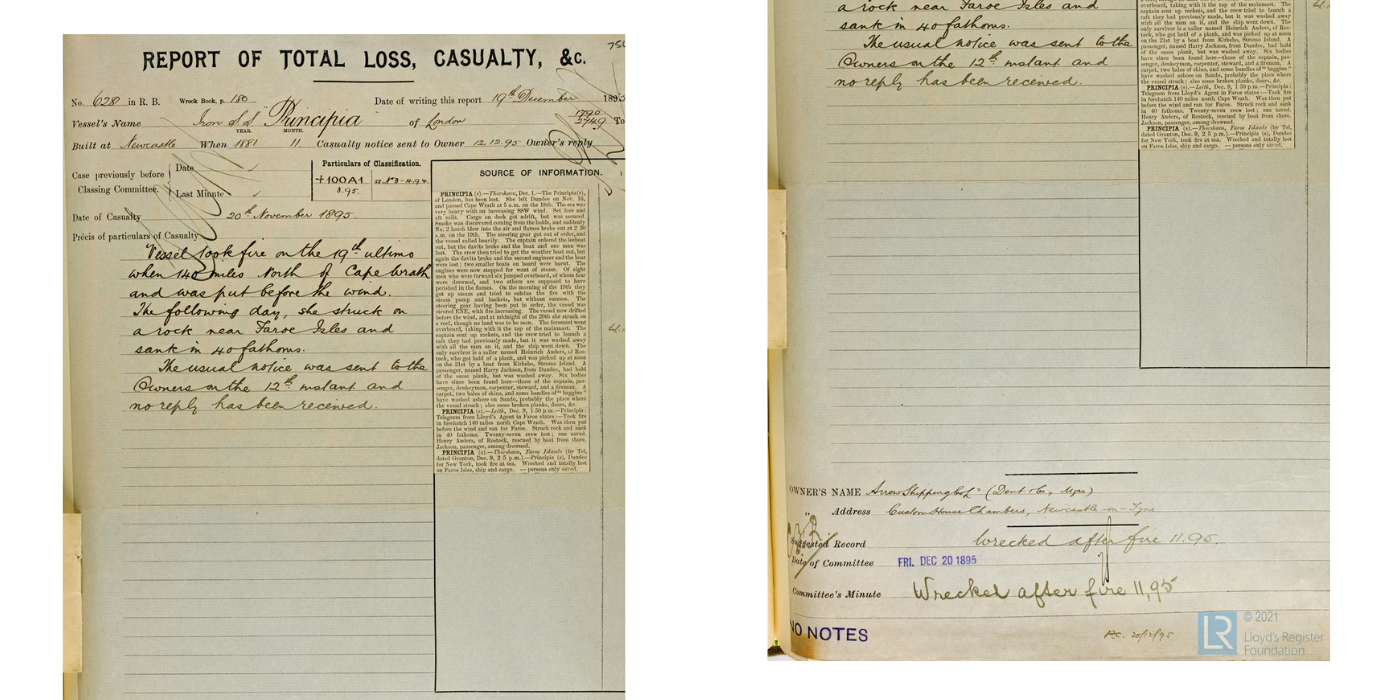

The Principia was an iron steamship that had been built under Lloyd’s Special Survey and rated A1. 14 At Dundee in Scotland, they were preparing to sail non-stop to New York. The hold was filled with a general cargo, as well as jute, and the hatches were now battened down with tarpaulins. They set sail on 16 November 1895, with 27 crew members and one passenger, but three days later the main hatch blew off, and flames burst out. Some men jumped overboard, and others were burned to death. Desperate attempts were made to contain the fire and reach land, but visibility was poor with the thick smoke, and on the 20th the Principia struck a reef near the Faroe Islands and sank. The only survivor was Heinrich Anders, a seaman from Rostock, who was found clinging to a plank. 15

At the Board of Trade inquiry at Newcastle a few weeks later, the managing owner, Mr Dent, gave his opinion that the fire originated at Dundee when somebody down in the hold emptied their pipe. He added: ‘The regulations against smoking in Dundee were very strict, but they had nevertheless caught men at it.’ Captain Castle, the Board of Trade Inspector, commented: ‘They had great trouble with stowaways. They found them under the boilers and in the bilges. They had found as many as five and six just after crossing the bar.’ The cause of the fire was uncertain, but the idea that it was started by hot embers from a pipe was unchallenged.16

Loss of the Principia in 1895

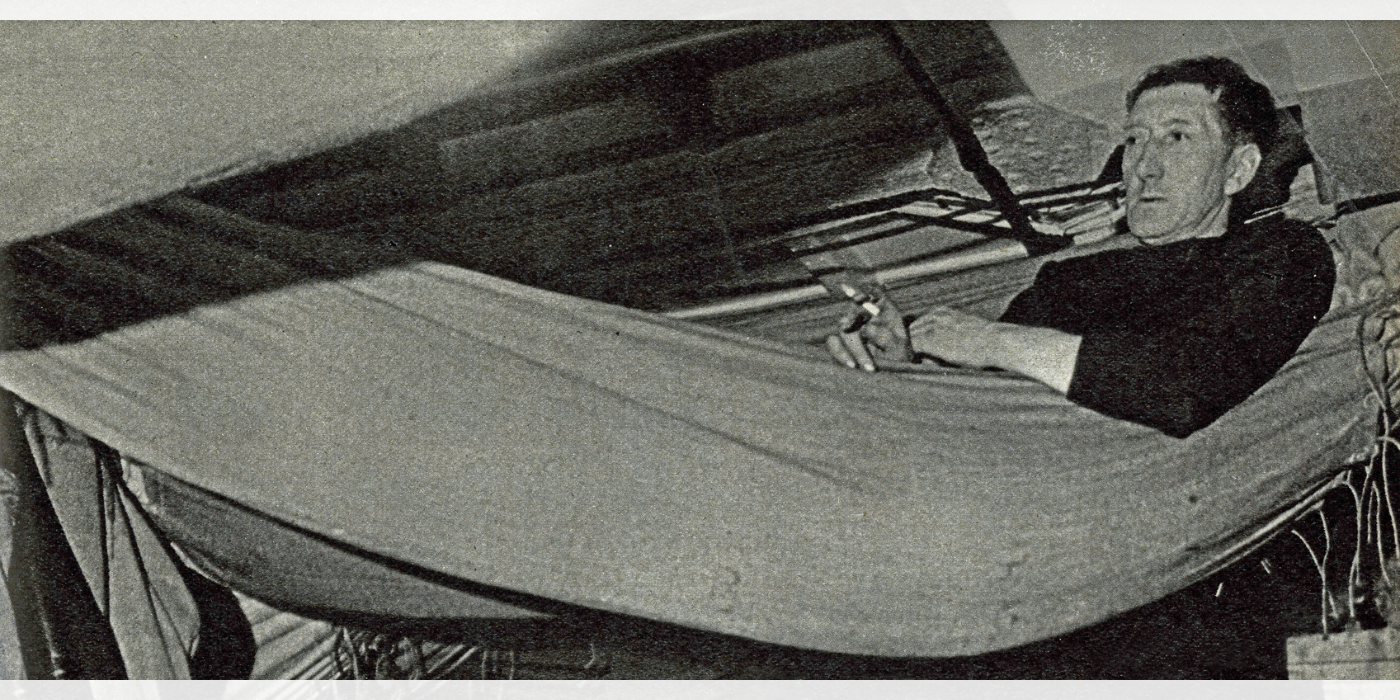

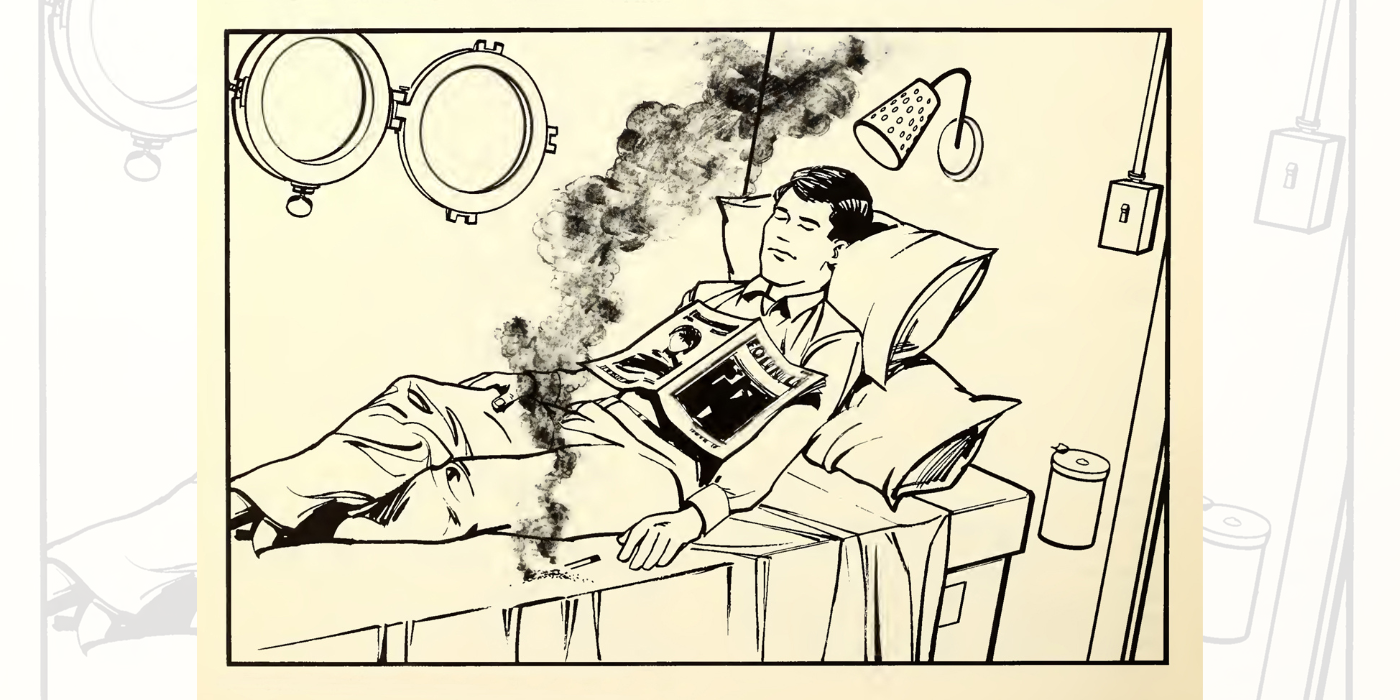

Smoking in a hammock

Smoking in bed on board ship

The Mombassa was another cargo steamer, built of steel under Lloyd’s Special Survey only three years previously, and rated A1. 17 She sailed from Calcutta (now Kolkata) in India on 19 December 1902 with a cargo of jute, but caught fire about 60 miles north of Madras and was abandoned on the 23rd. At the inquiry in January, the captain was certain that smoking was not to blame: ‘I superintended the loading of the jute. Some of the jute was damp ... Nobody could possibly have access to the lower bales, where the fire broke out, owing to the tight stowage. It is certain that no one could have set the lower bales on fire ... no smoking would be allowed anywhere near the hatches.’ 18 First published in 1858, On the Stowage of Ships warned that jute had a tendency to swell, especially if the ground tier was damp, and spontaneous combustion could then occur, as may have happened with the Mombassa. 19 Nevertheless, the stevedores and other dock workers were notorious for reckless smoking, even though it was banned in most dockyards. A carelessly discarded cigarette end or pipe embers could leave a cargo smouldering for days before erupting into flames.

In November 1874 the Cospatrick was destroyed by fire,20 with the loss of virtually everyone on board, including 429 emigrants heading to New Zealand. The tragedy was blamed on an emigrant searching for alcohol in the hold by the light of a candle or match. The disaster unsettled the seafaring world, as one captain of a steamship expressed: ‘Probably no more appalling tragedy of its kind than the burning of the emigrant ship Cospatrick ever occurred on the ocean.’ He mentioned that emigrants tended to bring on board hazardous lucifer matches, rather than safety matches:

He ... stocks himself with a large quantity of cheap lucifer matches of the most inferior quality. There is a law against the carrying of the latter dangerous article by passengers, but anyone who has made a voyage in an emigrant ship will remember the constant crackle and flash of the match as the smoker lights his pipe, at a companion way, or other sheltered spot. A few months back, a startling instance of the danger of fire from this cause alone came under my observation in an emigrant ship. The luggage was being hurriedly struck into the hold, and a portmanteau on being unslung emitted smoke from the interstices of the cover. It was hoisted on deck, opened, and among its contents were two boxes of wax vestas, each containing several hundred matches, which had caught fire by the shock of the portmanteau striking the lower deck. These had set fire to the linen, and it is highly probable that had the smoke not been noticed the ship would have been on fire in a few hours.21

The same captain also admitted that merchant seamen were careless:

It is to be regretted that in all classes of merchant ships smoking below is an acknowledged custom. Jack lies on his dirty bed of straw with pipe in mouth, reading some old scrap of newspaper, or the pages of a novel, and not unfrequently falls asleep with the burning embers beside him. The mystery is not why the Cospatrick was burned, but why such accidents are not constantly occurring from this and other causes.22

In his opinion, fires on board were the greatest danger: ‘Of all the perils of the sea, fire is decidedly the most to be feared. Men fight cheerfully to the last against wind and sea, but there is something in the cry of fire on shipboard which damps the energy of the bravest, because, in many instances, its origin or position are unknown.’ More than eight decades later, in a 1957 booklet, the Ministry of Transport still blamed smoking more than any other reason for fires on board ships:

Lighted cigarettes smoked surreptitiously are abandoned in combustible cargo and cause fires which smoulder unnoticed for days before bursting into flame. They are thrown away on deck where the wind catches them and blows them into an open port, hatch, or ventilator where they may land on inflammable material. They are left on the edges of ashtrays in the saloon or dropped from men’s hands as they fall asleep. 23

Unpredictable human behaviour resulted from dependence on tobacco, and it is unfathomable that it was allowed to remain a hazard. Some two decades afterwards, in 1979, the Maritime Training Advisory Board in the United States published Marine Fire Prevention, Firefighting and Fire Safety, in which it highlighted smoking: ‘Smoking is a habit. For some people it is so strong a habit that they “light up” without even realizing they are doing so. For others, nothing can quiet the urge to smoke; they will do so without regard for the circumstances or location. And some simply don’t care or don’t realize that smoking can be dangerous.’ The report was quite clear about the main source of fires: ‘At the top of every list of fire causes—aboard ship or on land—is careless smoking and the careless disposal of lit cigarettes, cigars, pipe tobacco and matches.’ 24

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the Lloyd’s Register Group or Lloyd’s Register Foundation.

Heritage Crafts, Clay Pipe Making

Video of How It's Made Replica Clay Pipes

Video of Making Clay Pipes at Broseley, Shropshire, in 1938

Institute of Nautical Archaeology (INA), Monte Cristi Shipwreck Excavation

Find out more about The Cospatrick disaster

Read more on Hindsight Perspectives: Fire at Sea

Footnotes

-

1

For a history of tobacco, see Iain Gately 2001 La Diva Nicotina: The Story of How Tobacco Seduced the World (London: Simon & Schuster), published in the US in 2002 as Tobacco: A Cultural History of How an Exotic Plant Seduced Civilization (New York: Grove Press).

-

2

Anthony Chute 1595 Tabacco: The distinct and severall opinions of the late and best Phisitions that have written of the divers natures and qualities thereof (London: Adam Islip). See p 20 for his comments on the plague – London had a severe outbreak in 1592–3. See also John Peter Taylor 2022 The Origins and Maritime Expansion of the Tobacco Pipe Trade of Southern England: An Archaeological and Historical Study, 1585–1640 (University of Liverpool doctoral thesis), pp 13–16.

-

3

Evan T Jones (ed) 2019 „Bristol Annal: Bristol Archives 09594/1‟, p 47 (PDF here). See also Gately 2001, pp 44–8.

-

4

Published in Frederick J Furnivall 1877 Harrison’s Description of England in Shakspere’s Youth, Part I, The Second Book (London: N Trübner & Co), Appendix I, p lv – in a section on tobacco (pp lv–lvi), which Harrison attributed to 1573. Taylor (2022, p 324) thinks this is too early to have been a clay pipe.

-

5

Horace Walpole (translator) 1797 Paul Hentzner’s Travels in England, During the Reign of Queen Elizabeth (London: Edward Jeffery), p 30

-

6

See, for example, Taylor 2022, Table 3.7 (Consignments of tobacco pipes from London destined for East Coast ports).

-

7

Taylor 2022, pp 28–30; Maritime Archaeology Sea Trust website at https://thisismast.org/projects/alderney-elizabethan-wreck.html

-

8

James P Delgado (ed) 1997 Encyclopaedia of Underwater and Maritime Archaeology (London: British Museum Press), pp 283–4; Jerome Lynn Hall 2006 ‘The Monte Cristi “Pipe Wreck”’ in Robert Grenier, David Nutley and Ian Cochran (eds) Underwater Cultural Heritage at Risk: Managing Natural and Human Impacts (Paris: ICOMOS), pp 20–2.

-

9

Jeremy N Green 1977 The Loss of the Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie Jacht Vergulde Draeck, Western Australia 1656 (Oxford: British Archaeological Reports Supplementary Series 36 part i). The clay pipes are described on pp 152–68. The box was too fragile to recover.

-

10

Amoret and Christopher Scott 1981 Smoking Antiques (Princes Risborough: Shire)

-

11

Lloyd’s Register of British and Foreign Shipping (From 1st July, 1908, to the 30th June, 1909), volume II: Sailing Vessels (London).

-

12

J H Wood 1969 ‘Voyage in the “Rowena”’ Sea Breezes 43, pp 215–17.

-

13

Roy and Lesley Adkins 2008 Jack Tar: Life in Nelson’s Navy (London: Little, Brown), pp. 91–3.

-

14

Lloyd’s Register of British and Foreign Shipping (1st July 1893 to the 30th June 1894), volume I – Steamers (London).

-

15

The Dundee Advertiser 12 November 1895, p 2. The crew members who perished were listed in the South Wales Daily News 10 December 1895, p 5. See also Lloyd’s Register of British and Foreign Shipping: Returns of Vessels Totally Lost, Condemned, &c. (1895) and also ‘Report of total loss or casualty for Principia, 19 December 1895’

-

16

The Board of Trade Inquiry took place on 4 February 1896 (Shields Daily Gazette 5 February 1896, p 3).

-

17

Lloyd’s Register of British and Foreign Shipping (From 1st July, 1902, to the 30th June, 1903). Volume I: Steamers (London).

-

18

Indian Daily News 8 January 1903, p 17; see also Lloyd’s Register of British & Foreign Shipping: Returns of Vessels Totally Lost, Condemned, &c. 1st October to 31st December, 1902.

-

19

Robert White Stevens 1858 On the Stowage of Ships and their Cargoes (Plymouth: Stevens; London: Longmans), p 81.

-

20

-

21

See p 369 of 'The Dangers of the Sea' Fraser’s Magazine 11 (March 1875), pp 368–72.

-

22

See p 369 of 'The Dangers of the Sea' Fraser’s Magazine 11 (March 1875), pp 368–72.

-

23

Liverpool Daily Post 3 December 1957, p 8, quoting from the booklet Fire in Ships.

-

24

Maritime Administration US Department of Commerce 1979 Marine Fire Prevention, Firefighting and Fire Safety (Washington DC: Maritime Training Advisory Board), pp 3–4.