Of the countless ships that disappeared without trace, a problem with ballast was the likely cause of many of the disasters. Although ballast was out of sight at the bottom of a ship, it was essential for maritime safety. The loading of a sufficient weight of ballast and its careful stowage were crucial for vessels at sea, round the coast and in port. Many accidents and shipwrecks were caused by too little ballast, too much ballast or the shifting of insecure ballast.

The history of ballast is a hidden one (see Ballast: A Hidden History on How to Avoid Shipwreck)1, and yet this massive industry was essential for the safety of every vessel worldwide. Disasters due to the state of the ballast occurred through negligence, risk-taking and ill-luck. In his An Universal Dictionary of the Marine, published in 1769, William Falconer said of ballast:

Stiffness in ballasting is occasioned by disposing a great quantity of heavy ballast, as lead, iron, &c. in the bottom, which naturally places the center of gravity very near the keel; and that being the center about which the vibrations are made, the lower it is placed, the more violent will be the motion of rolling. Crankness, on the other hand, is occasioned by having too little ballast, or by disposing the ship’s lading so as to raise the center of gravity too high, which also endangers the mast in carrying sail when it blows hard ... and a ship that loses her masts is in great danger of being lost.2

Almost a century later, Robert White Stevens, a printer at Plymouth and a Times correspondent, put a discussion about ballast in the opening paragraphs of his 1858 book on the stowage of cargoes. As very little had changed, he copied Falconer’s words of warning almost verbatim.3

A seaman ‘in ballast trim’

Shifting ballast on a Margate packet

The ballast and cargo in sailing ships needed to counterbalance the substantial weight of sails, masts, spars and rigging, as well as the force of the wind. Ships with too much ballast were regarded as stiff. Their centre of gravity was too low, and they were liable to roll excessively and violently, so that men working aloft might be thrown off and masts damaged or lost. Vessels with insufficient ballast, or none at all, were unstable and described as crank or tender. Because their centre of gravity was too high, they were at risk of falling over and capsizing. The effects of being stiff or crank were also experienced in steamships, as they could be just as unstable as sailing vessels. Ballast was costly, both in time and money, as it could take weeks of hard toil to load and unload both ballast and cargo. This meant labour costs, as well as the expense of purchasing ballast, which could rarely be resold. Rather than take proper precautions, it was easier – particularly for the owners – to ignore the dangers and run risks to reduce costs, especially for short trips and coastal voyages. 4

In his diary entry for 16 May 1874, Captain Rufus Randall of the barque Oasis recorded leaving St John in New Brunswick, Canada, with a cargo of deals (lengths of timber) destined for Bristol in England: ‘At 11am, tow out the harbour of St John. At 12.30 steam boat let go outside Partridge Island. Wind from SE. The Bark verry crank lopping down on her side (lop-sided). Wind freshening in the night & haul from SSW. I take a Bay Pilot pay $40.’ He then commented on the cargo and ballast: ‘CARGO. 438½ Standard deals & ends, 240 tons ballast estimated. Draft of water aft 20.2, forward 19.6. Not stiff enough.’ Captain Randall knew he had problems and so was lucky not to have encountered heavy weather before reaching Bristol safely on 12 June. 5

Being in port might seem a safe environment, but accidents due to a lack of ballast could occur. The General Caulfield was a wooden barque built in 1859 and rated A1 by Lloyd’s Register.6 On 5 August 1878, after being repaired at North Shields on the Tyne and not yet having any ballast, the plan was to move her out of the dock while being supported by a hulk on each side. Before the second hulk came into position, it all went wrong, as one newspaper reported:

Yesterday great alarm was occasioned at Messrs. Smith’s dock, North Shields, owing to the capsizing of a ship. It appears that while preparations were being made for taking out of dock the barque General Caulfield, belonging to Mr Southern, of Newcastle, which had been undergoing repairs, and she having no ballast, only one of the hulks intended to keep her upright was got in when she suddenly capsized. No one was injured.7

In the often crowded conditions of ports, the capsizing of a vessel could be catastrophic. The Magdala was a wooden barque built under special survey in Canada in 1868 and rated A1 by Lloyd’s Register. 8 On 15 September 1880, with no ballast, she fell over sideways in the London Docks, ‘on her beam ends’, meaning that her beams were vertical, making it difficult or impossible to right herself:

About eight o’clock on Wednesday morning the Magdala, of 1,400 tons burden, which had arrived in the Hermitage Basin of the London Docks, after discharging her ballast, was taken by a violent gust of wind and thrown on her beam ends. The houses on the eastern side had a very narrow escape, the masts bearing right on them. The walls of the dock partially saved her, as also her being moored near to another vessel. Hydraulic power was used, and she was brought upright, but several of the crew on board sustained serious injuries. 9

Any vessel was vulnerable until completely loaded and ‘trimmed’ – the spreading and securing of ballast and cargo so that the ship floated on an even keel, not too high at the bow or stern and not listing to one side. At times sailing ships used external ballast logs suspended by chains for stability, especially at ports in Scandinavia and the Pacific North-West. Before the ballast was dug out and the cargo loaded, four substantial logs were floated alongside the vessel and then held fast above the water by chains, but it was not a foolproof system, as vessels did still capsize.10

The Baron Aberdare, in ballast and capsized

The Baron Aberdare in Australia before the 1883 accident

The iron barque County of Flint

Even if a ship was stable at the start of a voyage, the movement caused by strong winds and heavy seas could make ballast shift with disastrous consequences if it was not securely stowed. In 1935 Captain James Bisset was listening to old mariners swapping yarns, including one who over three decades earlier had served aboard the County of Flintan iron barque registered at Liverpool and rated ✠100 A1 by Lloyd’s Register. 11 After unloading a cargo of coal at Callao in Peru, they set sail in ballast to the Chincha Islands, over 100 miles away:

We had stone ballast – round pebbles – and very shifty stuff. One night during a heavy squall it shifted as she heeled and over she went on her beam ends with the fore topmast snapped off short. We spent two days and two nights in the hold shovelling stones to windward before we got her upright again. Then we had to rig the spare spar as a jury topmast and after three weeks of hell let loose we limped in between the islands and dropped anchor. 12

Others were not so fortunate. In November 1897 news reached Britain from Chile of the loss of the Cordillera: ‘A Lloyd’s Valparaiso telegram states that the Cordillera’s ballast shifted, and the vessel was thrown on her beam-ends during a heavy gale, and capsized later on off Valparaiso. She was abandoned the next day (November 8), and is supposed to have foundered.’13 The Cordillera was also an iron barque, built under special survey at Liverpool in 1866 and rated ✠A1 by Lloyd’s Register. 14 Six weeks after the disaster, the full story appeared in British newspapers:

On Sunday, November 7, the British barque Cordillera, of 788 tons, Captain E.A. Everett, left Valparaiso in ballast for Caleta Buena, there to load a cargo of nitrate for Europe. She was loaded hurriedly, and when she sailed was about six inches down by the head. Before the crew had got the anchors up and any sail on her, the tugboat Adela, which was towing her out, left her without any warning, and when the sails were set it was found that the ship would not steer. About five hours after the Cordillera had quitted her moorings, the ballast, which was sand, began to shift, and when, an hour later, a heavy squall struck her, she listed right over, her lee rail being under water. For a whole night the barque remained on her beam-ends and then the crew abandoned her, taking to a raft after all the boats had been lost or smashed. 15

The crew clung to lifelines on the raft, but within 24 hours most of them were exhausted and drowned. Three survivors were spotted by the steamship Cachapval and taken to Valparaiso.

The iron barque Cordillera

The Culmore steel ship

Sand was particularly problematic as ballast, shifting easily. The most effective way of keeping sand secure was to install ‘shifting boards’, which were upright wooden planks that formed compartments. The Culmore was a three-masted steel sailing ship built under special survey at Glasgow in 1890 and rated ✠100 A1 by Lloyd’s Register.16 In October 1894 she discharged a cargo of nitrate at Hamburg in Germany, where Captain Hawkins, the marine superintendent of the company that managed the ship, ordered her new master, Captain Archibald R Halliday, to install shifting boards in the main hold and take on board 500 tons of sand as ballast. The Culmore then went into dry dock for a survey, after which a further 420 tons of sand were loaded in readiness for the passage across the North Sea to Barry in Wales for a cargo of coal intended for Rio de Janeiro.

On 4 November the Culmore left Hamburg with about 26 crew members, as well as the master’s wife Isabella, but soon encountered contrary weather, which turned severe. Some 100 miles from Spurn Point, on 14 November, the sand ballast shifted, because the shifting boards had not been fitted. A summary of events was compiled from the evidence of survivors at the official wreck inquiry in January 1895: ‘About 6 a.m. on the 14th ... the master ordered all hands on deck ... While at work securing the anchors they found the vessel taking a heavy list to starboard, and realised that the ballast was shifting. Hands were at once sent into the hold to trim the ballast to windward.’ The vessel became unmanageable, and so they also attempted but failed to remove the topmasts: ‘The vessel was now almost on her beam ends. The efforts of the hands in the hold were of no avail with the ballast, as the ship was throwing it to leeward faster than they could shovel it to windward. They were called up, and the hatch battened down ... By this time the vessel was on her beam ends, and all hands had to get out on the port side.’ 17

The Culmore eventually sank, and although the steam trawler Swift tried to rescue the crew, there were only four survivors. Captain Halliday and his wife were also rescued, but immediately died of their injuries.18 At the inquiry, the Court was told that the sand was dredged from the River Elbe, and when a sample was produced, it was compared to quicksilver, a dangerous type of ballast, though it appeared more manageable when damp. The company’s marine superintendent, Captain Hawkins, was blamed for not ensuring that the shifting boards were fitted, and such was the gravity of his negligence that he was ordered to pay £50 towards the expenses of the inquiry.

No matter how highly rated the ship or how good the crew, if the weight of ballast was wrong or if it was not trimmed and secured, accidents could occur. In only a few shipwrecks were there survivors who witnessed the shifting of ballast, but this was the likely cause of innumerable vessels disappearing without trace. Steamships were not immune. During the Second World War, so-called ‘Liberty’ steamships were built in the United States, and ballast had to be loaded between the decks to reduce stiffness, as one inquiry stated: ‘There is no doubt that in ordinary ballast conditions “Liberty” ships are “stiff” and therefore subject to somewhat heavy rolling which naturally affects their manoeuvrability. Accordingly, the practice was adopted of placing solid ballast on board such vessels in order to make them more manageable when carrying out ballast voyages in convoy.’19 The Sameravon was one example, and in December 1944 she left London in ballast, heading for the Atlantic in a wartime convoy and loaded with 2,025 tons of Thames ballast. No shifting boards were used, and in a storm off the Newfoundland Banks the ballast suddenly shifted, causing the ship to list 55 degrees to starboard. Luckily, the crew managed to re-stow the ballast and reach port safely.20

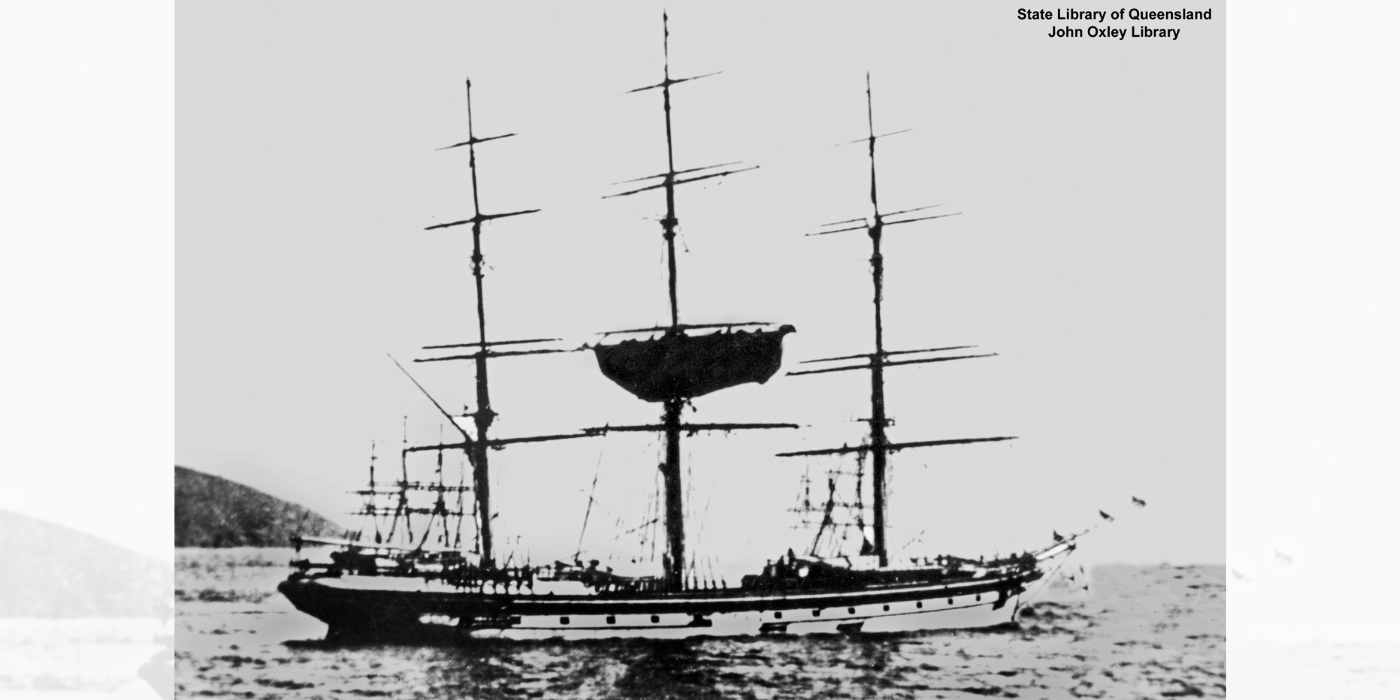

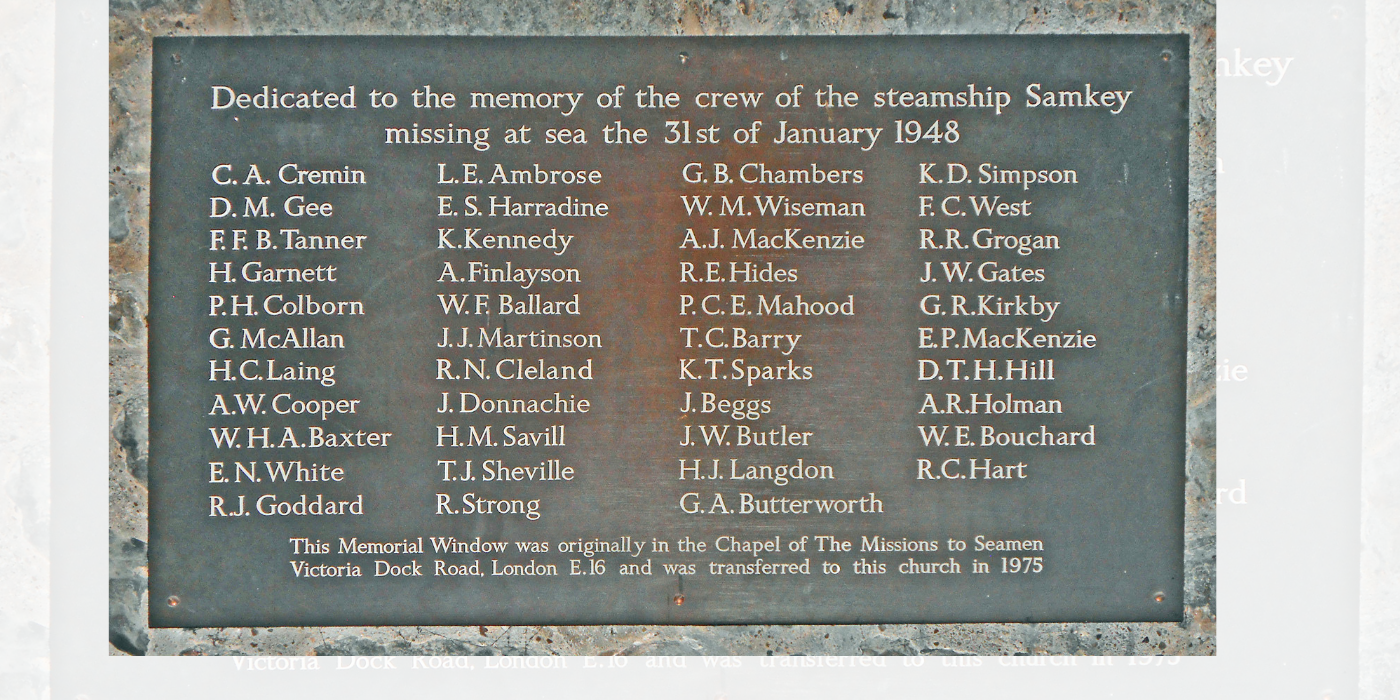

After the war, in January 1948, her sister ship, the 7,219-ton steamship Samkey, disappeared in the Atlantic on her way from London to Cuba in ballast. She had 1,500 tons of ballast between the decks, and at the official inquiry the Court concluded that ‘the s.s. “Samkey” was lost with all hands due to a sudden shift of the solid ballast in the ’tween decks during heavy weather’.21 The inquiry assumed that the Samkey had Thames ballast, but a clerk from the firm of William Cory & Son later said this was wrong: ‘We had instructions ... that the Samkey was to be supplied with 1500 tons of dry sand ballast, and we loaded seven barges with special dry ballast, all taken from land pits.’22 That same year, the 7,266-ton Liberty steamship Leicester, formerly the Samesk, left London in ballast, and for this voyage William Cory & Son provided 1,238 tons of Thames ballast made up of 50 per cent sand and 50 per cent stones, as well as another 250 tons of dry-pit ballast. Some three weeks later in appalling weather, about 900 miles east of New York, the vessel lurched 50 degrees to port and had to be abandoned. Six crew members lost their lives, but the rest were rescued. It was believed that insufficient and weak shifting boards were to blame for this ballast disaster.23

Samkey memorial window

The Samkey commemorative plaque

There was always a danger of ballast moving if not properly secured, and decades earlier the Liverpool Journal of Commerce commented:

Ships carrying sand, and similar stuff, are often extremely dangerous in ballast trim. Not infrequently the logbooks of tramp steamers westward bound in the North Atlantic contain entries setting forth that the sand ballast shifted consequent on the steamer’s heavy rolling in a gale of wind. Curiously enough such warnings are not regarded by masters nearly so seriously as they deserve to be. She is permitted to court disaster once too often, and is eventually counted among the missing. Several fine sailing ships in ballast disappeared during the past few months.24

After considering the expense of ballasting a ship in terms of money, time and labour, as well as the pressure from the owners of the vessel to make a profit, the writer concluded: ‘We cannot forget that the ship-master is the responsible person. He holds the position of nautical adviser, as it were, in such matters to his employers, and has not the least right to imperil the lives of all hands, together with valuable property, by taking a ship to sea insufficiently or improperly ballasted.’

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the Lloyd’s Register Group or Lloyd’s Register Foundation.

Read the part 1 of the Ballast story here

Naval History and Heritage Command National Museum of the U.S Navy/ Information on Liberty Ships

Footnotes

-

1

-

2

William Falconer 1769 An Universal Dictionary of the Marine (London: T. Cadell), unpaginated.

-

3

Robert White Stevens 1858 On the Stowage of Ships and their Cargoes (Plymouth: Stevens; London: Longmans), p 9.

-

4

Martin Lee 2000 ‘The ballasting of the twentieth-century deep water square rigger’ The Mariner’s Mirror 86, pp 186–96; David B Clement 2021 Square-Rigger Sunset: The Passages of Four and Five-Masted Ships and Barques volume 1 (Exeter: The South West Maritime History Society), pp 112–13.

-

5

Capt. Rufus S. Randall’s Pocket Diary for the Year 1874, held in the Nathan R Lipfert Research Library at Maine Maritime Museum.

-

6

Lloyd’s Register of British and Foreign Shipping, from 1st July 1877, to the 30th June, 1878 (London, 1877)

-

7

York Herald 6 August 1878, p 6.

-

8

Lloyd’s Register of British and Foreign Shipping from 1st July, 1878, to the 30th June, 1879 (1879, London)

-

9

The Weekly Dispatch 19 September 1880, p 5; Sunderland Daily Echo and Shipping Gazette 17 September 1880, p 3. The vessel is listed in The Mercantile Navy List and Maritime Directory for 1881, p 399, as belonging to James R de Wolf of Liverpool, 1,140 tons.

-

10

Frank Scott 2016 ‘Ballast Logs’ The Mariner’s Mirror 10, pp 335–7; David B Clement 2021 Square-Rigger Sunset: The Passages of Four and Five-Masted Ships and Barques volume 1 (Exeter: The South West Maritime History Society), p 113.

-

11

See Lloyd’s Register of British and Foreign Shipping volume II – sailing vessels, from 1st July, 1895, to the 30th June, 1896 (London, 1895). The County of Flint was built in 1877 and by 1906 was called Zelbio.

-

12

See pp 117–19 of J G Bisset 1935 ‘Memories of Sail’ The Seagoer 2 no 4, pp 111–24.

-

13

Liverpool Echo 10 November 1897, p 4.

-

14

Lloyd’s Register of British and Foreign Shipping from 1st July, 1895, to the 30th June, 1896. Volume II sailing vessels (London, 1895)

-

15

London Evening Standard 21 December 1897, p 6.

-

16

Lloyd’s Register of British and Foreign Shipping from 1st July, 1893, to the 30th June, 1894. Volume II sailing vessels (London, 1893)

-

17

Report from the Select Committee of the House of Lords on Light Load Line; together with the proceedings of the committee, minutes of evidence, and appendix 1903 (London: HMSO), pp 265–9.

-

18

Captain Archibald R Halliday is often wrongly cited with the initial ‘P’. See UK Registers and Indexes of Births, Marriages and Deaths of Passengers and Seamen at Sea 1891–1922. For the inquest, see The Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer 17 November 1894, p 6.

-

19

Report of Court (No. 795) s.s. “Samkey” O.N. 169788 (1948, London: HMSO), p 2.

-

20

Torbay Express and South Devon Echo 7 September 1948, p 3; Report of Court (No. 795) s.s. “Samkey” O.N. 169788 (1948, London: HMSO), p 4.

-

21

Report of Court (No. 795) s.s. “Samkey” O.N. 169788 (1948, London: HMSO); Torbay Express and South Devon Echo 7 September 1948, p 3.

-

22

Lloyd’s List & Shipping Gazette 28 June 1949 – see https://hec.lrfoundation.org.uk/archive/documents/lrf-pun-014124-014134-0081-o

-

23

Evening Herald (Dublin) 10 August 1949, p 1; Lloyd’s List & Shipping Gazette 28 June 1949 – see https://hec.lrfoundation.org.uk/archive/documents/lrf-pun-014124-014134-0081-o

-

24

Liverpool Journal of Commerce 29 January 1897, p 4.