As the National Geographic Endurance became the world’s most advanced polar expedition vessel (16th February 2022) to be granted the highest ice-class of PC5 Category A and Ernest Shackleton’s Endurance was re-discovered at the bottom of the Weddell Sea, it seems a pertinent time to think on polar voyages, on the efforts to break the ice, so it were, for colonizing nations’ dreams of the poles, and to reflect on why now, more than ever before, innovations in polar marine engineering are so important.

The much-publicized RSS Sir David Attenborough (known to many as the ship which should’ve been Boaty McBoatface, since then often taught as a business studies example for how crowdsourcing can fail) is currently on its way to deliver essential supplies to the British Antarctic Territory. Every inch of it is state-of-the-art technology that ensures the safety and survival of crew and cargo, and the durability and operative efficacy of the ship in the harsh environments of the poles.

To the imagination of its non-indigenous peoples, the poles represent the extremes. Insisting on entering them can only be for extreme purposes, be it extreme curiosity, romance or urgency. Polar exploration ships were hardly named the Erebus (a Greek mythological void on the way to the land of the dead) or the Terror in a spirit of expecting a comfortable journey, and whilst the Sir David Attenborough might be thought a radical rebranding of a polar voyage, Sir David Attenborough is widely considered a hero of natural curiosity. The poles are still places where the heroes brave and the rest can only imagine as impossible challenges.

As transit increases in the poles, it’s a good time to revisit those narratives, and examine how they’ve changed or stubbornly remained the same at heart.

In 2006, classification society Lloyd’s Register issued Provisional Rules for the Winterisation of Ships, providing an industry standard to protect the ship from the effects of low temperatures and ice build-up.

The careful and highly specific specifications of what makes a safe polar vessel reflect how dangerous polar journeys are. The centuries long hunt for a Northwest passage cost many lives and vanished many ships, each an experiment building on the failures of others as the risk of experimentation was seen as an economically worthy undertaking. The nation, or empires in the 19th to 20th century, which could find and navigate a passage that cut the time to reach Asia would rule the maritime industry – and possibly the world.

The Northeast passage, running along the Russian coastline from the Atlantic to the Pacific, has its value for the same reasons. Successfully traversed in 1879 by the converted whaling ship Vega, it has since become a route of grave importance. As the Suez Canal sees increased congestion, rising tariffs, and unpredictability due to the near-perpetual war and conflict in its surrounding regions increasing the costs of transporting goods through to and from Asia, the Northeast passage – on average 13 days shorter than going via the Suez - offers an alternative shortened, cost-cutting sea route.

The Vega may have left with Tromso, Sweden, in July of 1878 with very little fanfare, but it returned to Stockholm, April 1880 a celebrity. Its feat wasn’t repeated for 35 years, a testament to the difficulty of navigating polar seas.

The story of successfully navigating polar waters has long been tied to icebreakers. 1890, for instance, would be mentioned as significant for being the publication year of the influential ice-breaker design by Finland’s Robert Runeberg, realized in the construction of the Murtaja. Many features of present-day icebreakers owe themselves to Runeberg’s pencil. Other stories might mention the American efforts, with their distinctive circular saws on the vessels’ bows, as could be seen on the 1836 Hudson River paddleboat the Norwich, and how this design made its way to the Baltics to become a staple for icebreakers there between 1898 and 1977.

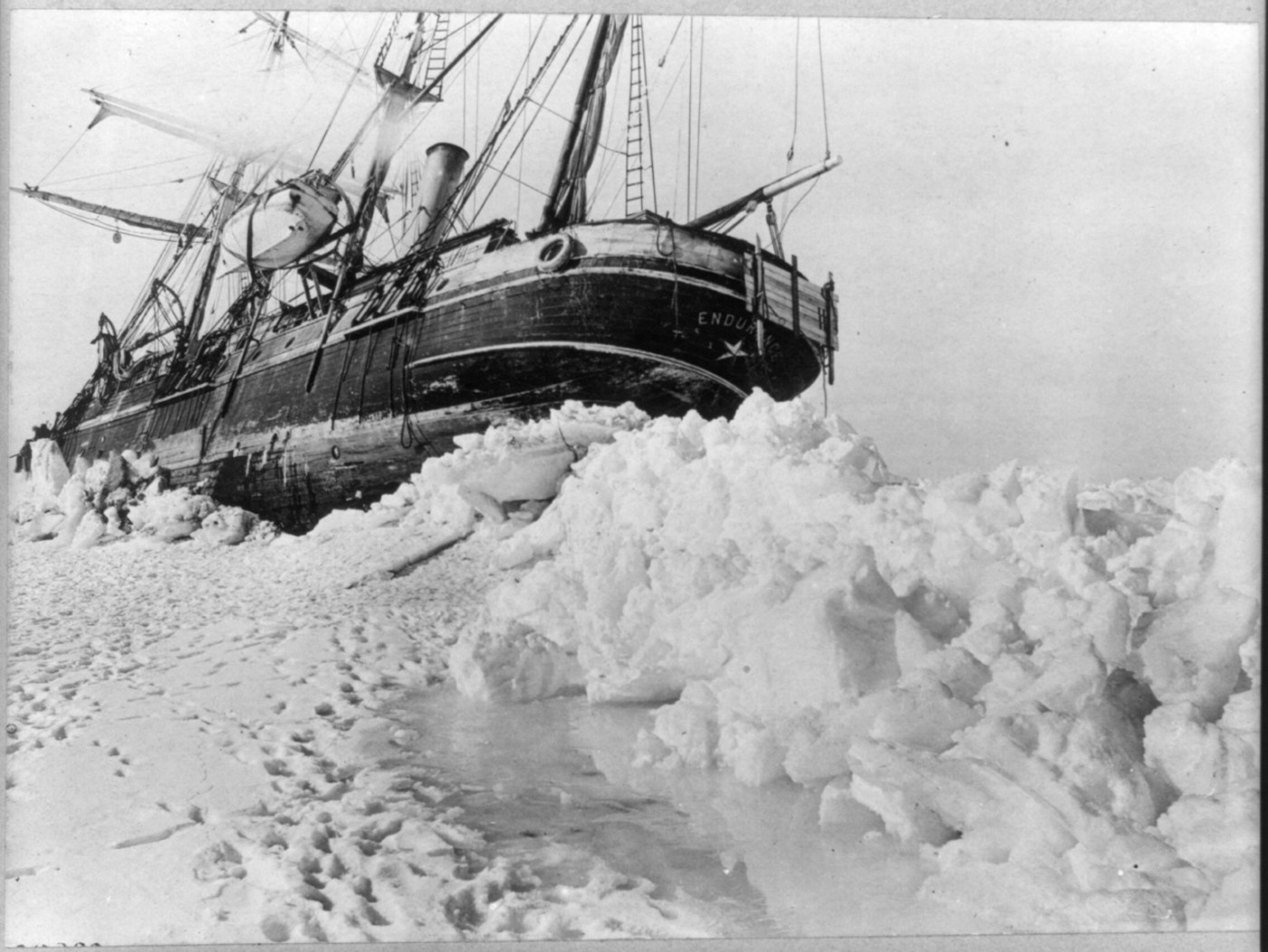

For much of the 20th century, the success of a ship in a polar region was primarily defined by its ability to withstand ice. We can see this no less in the case of Shackleton’s Endurance, which sank in 1915, crushed by sea-ice. Ice exploration has therefore long been a hot experimentation space for engineering and design innovations but to build ships suitable for travelling the poles, it’s no longer sufficient to develop the ship’s ice-breaking capacity alone.

HMS Endurance trapped in Antarctic pack ice, February 1915

Shackleton's expedition to the Antarctic last moments of the Endurance, 1916

Unlike early polar vessels, 21st century ships now reflect wider concerns regarding the environmental responsibilities. This, perhaps, marks the greatest shift in polar vessel technological development priorities since the shift from using converted whalers to building specialist steamers. Environmental consciousness may arguably be the new priority as the polar traffic has increased due to there being less ice at the poles.

Reflecting on polar vessel design is a direct confrontation with the fact that climate change is real, urgent and happening. One day, the icebreaking features of the ships may even, at the current rate, become redundant. The changing accessibility of the polar regions is a stark reminder that human activities occur in a wider natural world and have consequences upon it.

When we consider safe passage through the Northwest, Northeast or the South Pole regions continue, we’ve been forced as a global society to include in the idea of ‘safe passage’ the safety of the polar environments from us, rather than the us from the polar environments. The International Maritime Organization's (IMO) International Code for Ships Operating in Polar Waters, known as the Polar Code, entered into force on 1 January 2017. Mandatory under both SOLAS (Safety of Life at Sea) and MARPOL (International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships), it includes environmental protection commitments alongside provisions for protecting seafarers and ships. The RSS Sir David Attenborough is, in fact, the first Polar Code compliant vessel to be built in the UK.

Under the Polar Code, vessels are only permitted to discharge waste into the water if the ship carries a sewage treatment plant. Cleaning agents in washing water can only be discharged if they’re not harmful to the marine environment. Ships need to take measures with ballast water to prevent the movement of invasive species. If early polar exploration was defined by research and development in icebreaking technology, the 21st century has encouraged R&D in the legal instruments for implementing them. It does help that, in the 21st century, ships are now fitted with the tracking devices such as Automatic Identification System (AIS) and search and rescue systems such as Global Maritime Distress and Safety System (GDMSS) that mean ships can no longer simply vanish into the poles, their whereabouts unknown, as so many Northwest passage hunters did. Famously, the Franklin expedition of 1845 ended when the two ships simply disappeared in the ice. As ships can now be tracked even in the far-flung reaches of the poles, their transgressions can be spotted much more easily.

Altogether they build a narrative of how technological and legal innovations co-evolve as an expression of wider societal value changes. Polar exploration’s direct connections with climate change also draws attention to the urgent need to decarbonize the maritime industry. The stringent environmental considerations required for taking a ship through polar seas is contributing to decarbonizing debates. Taking advantage of emerging polar passages is all very well and good economically, but the image of grey exhaust fumes on pristine ice would only make a mockery of present industry efforts. The next step in polar exploration technological development will have to include clean, environmentally neutral fuel usage, which will have wider industry applications and demand.

Increased environmental consciousness has only been possible due to a significant narrative shift in our understanding of the poles. As mentioned already, ships given such cold and forbidding names as Erebus or Terror implied the poles to be inhospitable, unpeopled and lifeless. We now know and are making conscious choices to not ignore the facts that this is not the case, and the goal of cleaner shipping reflects that.

Lifeless ice that was free for irresponsible conquering is now lived ice with all the responsibilities that respecting life and living systems entails. They’re not Erebuses in which ships disappear, but corners of our living world with their own unique ecosystems and lives and livelihoods adapted to live in and with them.

The shame with polar exploration is that in internationalizing the poles through legislation and making their dominant narratives that of either global trade or global climate crisis is that it ignores to our detriment those who already call the poles their home. Of the approximately 40 million residents of the Arctic Circle, 10% of those are of indigenous groups from over 40 different ethnicities, and whilst international law may defend their rights there has been lukewarm effort to incorporate these rights at the national level. As polar transit increases, it’s likely that the port infrastructure to accommodate it will appear along the coastline along with their supporting networks. Continued conflict in the middle east around the Suez Canal and worldwide congestion and delays in shipping means that the Arctic route is looking increasingly desirable, and once development begins it would potentially be rapid. If polar voyages are to be ‘safe’ and responsible, alongside environmental considerations there should be measures that local communities’ lives be safe from such development and how foreign capital is thrown about the area. Currently, however, there are no independent organisations representing the Arctic Indigenous Peoples at the International Maritime Organisation, the UN-backed body responsible for setting international maritime law. 2016 saw the first time that the IMO were directly addressed by representatives of Arctic Indigenous Peoples from Alaska, Canada and Russia.

Pre-20th century narratives of the poles painted them as people-less voids, dangerous places meant only for the undaunted risk-takers. The emphasis on icebreaker construction and development in their exploration goes hand-in-hand with this view, as the polar passages became sites of conquest for individual, imperially backed, ambitions.

In the 21st century, whilst the challenge to develop ships that can withstand the crushing forces of ice is still key, research and development and risk-taking experimentation can no longer be limited to feats of engineering. We need human tools, from the humanities and the social sciences, to reflect the human poles. That we have begun to develop legislation to protect the seas and the humans living off them (slow and sluggish as these efforts seem to be) indicates the shifting narrative, and we can look forward, hopefully, to a continued shift.

What both polar engineering and legal innovations have shown us is that international cooperation does have significant impact. In terms of regulation, for all that the IMO has its flaws and its interests often called to question, it still provides an important forum space for raising international maritime issues and coordinating the necessary legal responses. In engineering, we can look to the Russian icebreakers of the early 20th century as an example. All were built in foreign shipyards, combining the subjective knowledge bases of those with practical first-hand knowledge of ice travel with, say, Lloyd’s Register’s surveyors, who could objectively study the ships with the aim of building expertise and recording innovations for further development.

Lloyd’s Register then continued to share its expertise on safety in ice-traversing vessels over the 20th and into the 21st century, surveying and classing such ships as the Tempera and Mastera in 2002, the world’s first double-acting tankers (DAT) (with a special propulsion configuration for going through ice both ahead and astern). With owners registered in Finland and built by Sumitomo Heavy Industries of Japan, Tempera was a truly international effort, as most ships are, but it’s particularly notable in polar-going vessels, because it shows how many nations would consider investing in - the still relatively dangerous activity of – polar voyaging as a risk worth taking.

Research and development is a risky, expensive business. We’ve continued to invest in polar marine technology for the same reasons as in the 19th century: the risk of failure and death is outweighed by the possible benefits of economic success. The fastest, most durable, most fuel-efficient and well-informed fleet, ready to take advantage of the melting ice, will reap enormous rewards against the competition.

Before the 20th century, the Arctic waters were only free of ice for two months of the year. Research published in 2020 suggests that the Arctic may be completely free of sea ice by 2035. As the RSS Sir David Attenborough and the National Geographic Endurance set sail, we can only wonder when ships of their kind, with all their design features to battle ice, will disappear and sink as Shackleton’s Endurance into the depths of history.

Author: Mina Ghosh is Research Assistant at the Lloyd’s Register Foundation Heritage & Education Centre. You can read some of Mina’s other work here: Self-driving cargo ships: will they be haunted by history?