Donkey engines and boilers were the work horses of sailing ships and steamships. They could operate machinery like winches, and crew numbers could be reduced. The word ‘donkey’ derives from when these animals provided a means of power, before the Steam Age. Donkey boilers (like all boilers under pressure) sometimes exploded, causing damage and deaths.

For centuries, the crews of seafaring vessels did all the manual work, until donkey engines and donkey boilers were introduced on board sailing ships and steamships. The donkey engine was driven by the pressure of steam produced by heating water in a small donkey boiler.

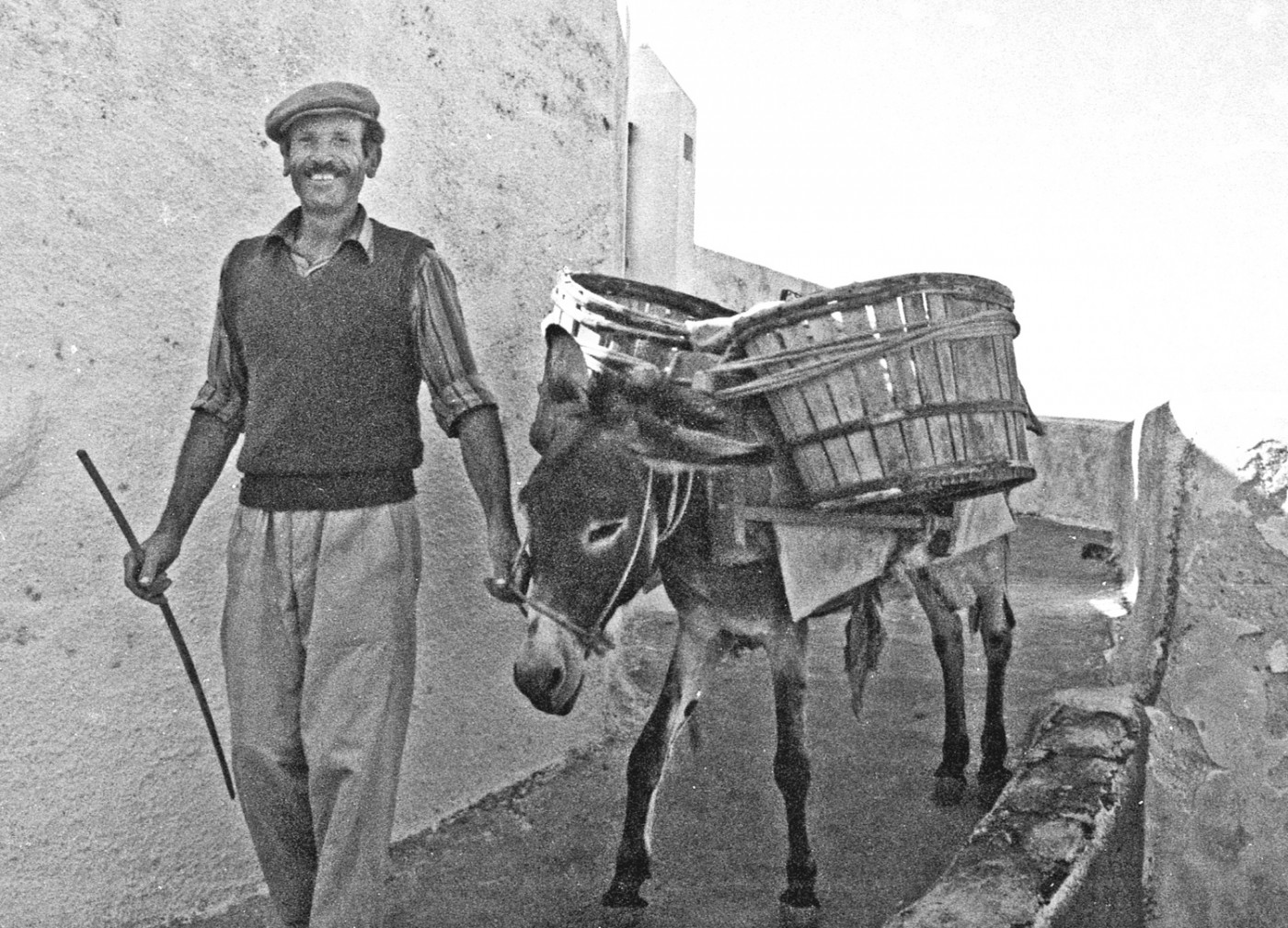

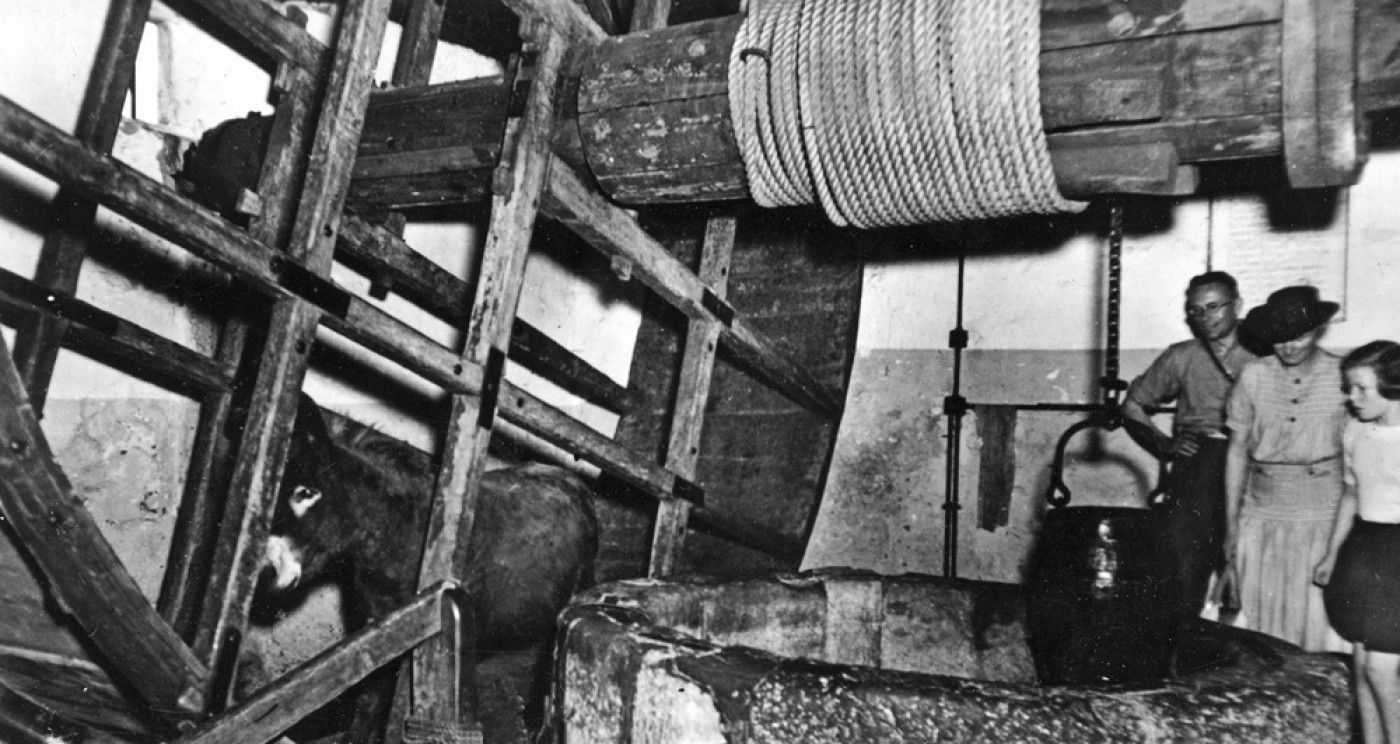

The origin of the curious names ‘donkey boiler’ and ‘donkey engine’ goes back to when donkeys on land were a source of power and traction, transporting heavy loads and people, pulling carts and sledges, and operating machinery by turning vertical treadwheels or treadmills and horizontal gins. Carisbrooke Castle on the Isle of Wight has the most famous donkey treadwheel, which is a popular visitor attraction. It is turned by a donkey walking round inside, drawing water from a well sunk 161 feet into the chalk. 1

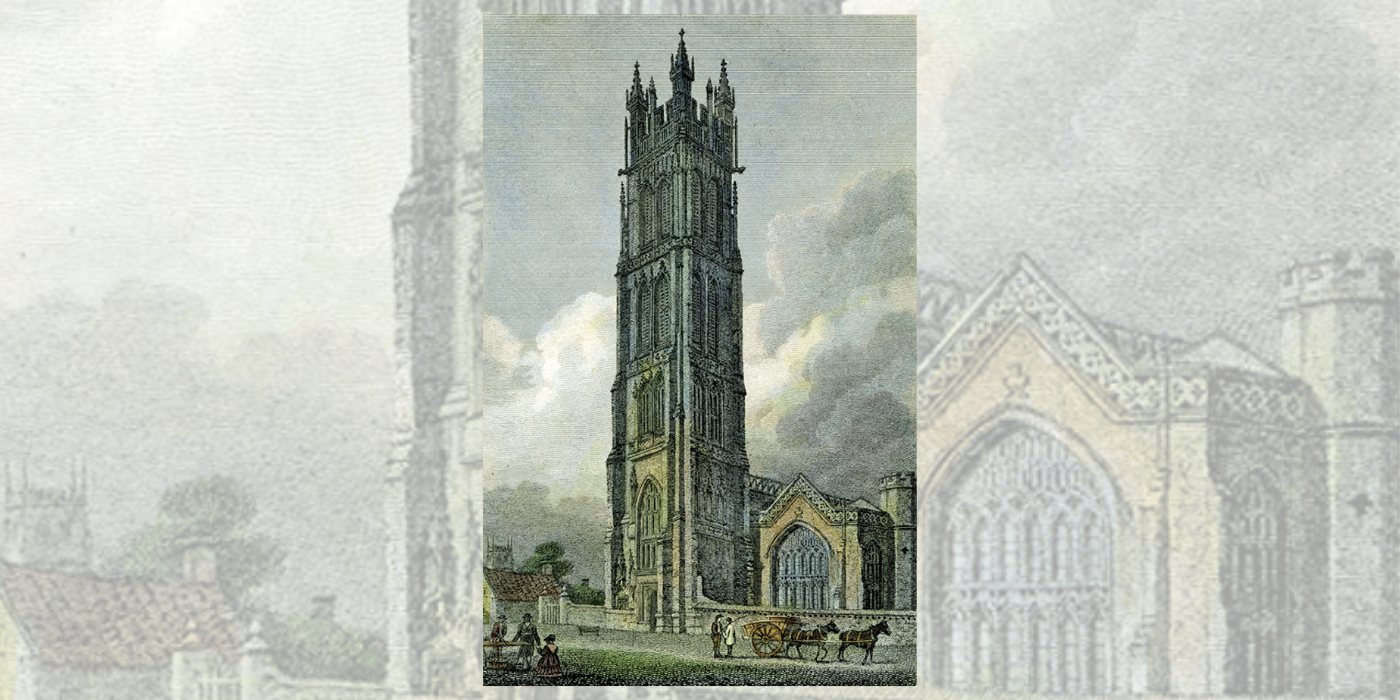

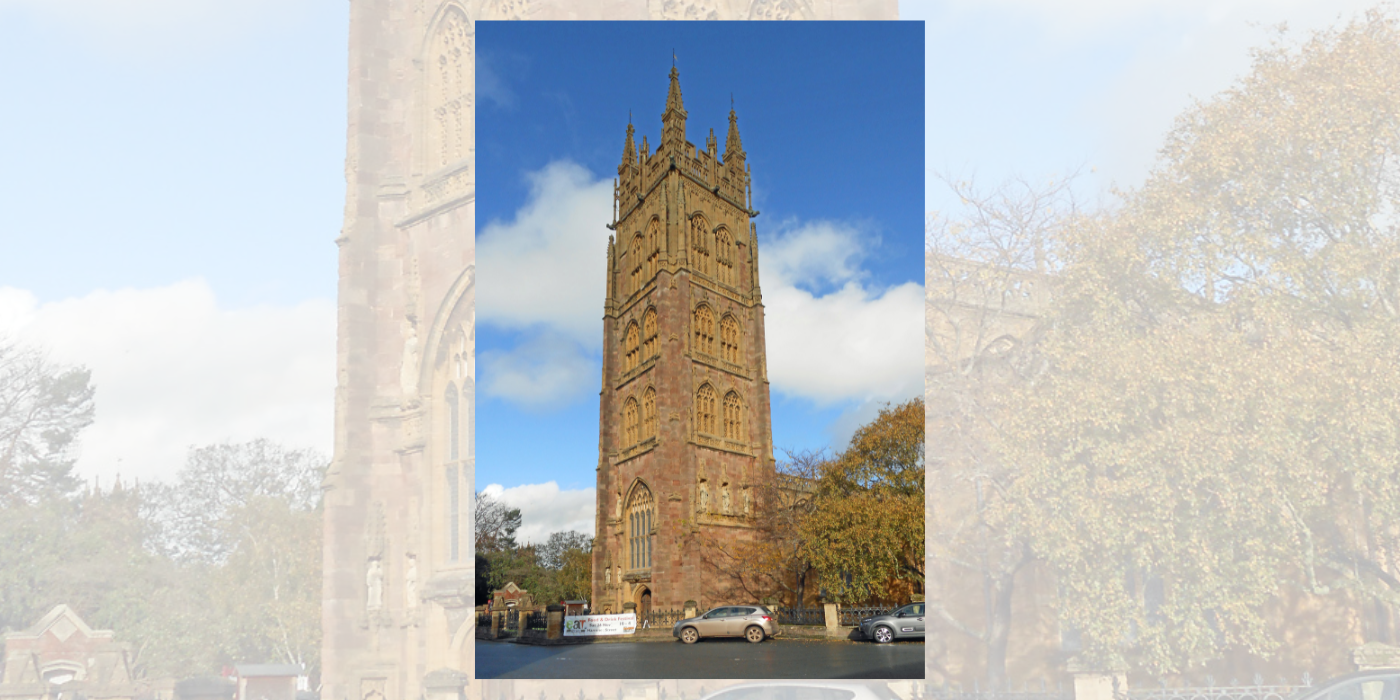

Donkeys were invaluable for simple haulage work. When the medieval tower of St Mary Magdalene’s church (now a minster) at Taunton in Somerset was being rebuilt in Victorian times, no exterior scaffolding was used. Instead, the workmen made a donkey trudge up and down the adjacent street with a rope attached that ran through a pulley and enabled construction materials to be hauled up. When completed in 1862, the tower measured 153 feet high, and in celebration the donkey itself was hauled to the top to enjoy the view. 2

The word ‘donkey’ was only adopted in the late 18th century – previously, the word ‘ass’ was commonplace. A female donkey was referred to as a ‘jenny’ and the male a ‘jack’ or ‘jackass’. Anyone regarded as stupid or silly was often called a donkey, probably because donkeys had a reputation for being slow, stubborn and placid, and ‘donkey work’ became a term for drudgery. In the 19th century, millions of ‘donkey stones’ made from crushed stone and cement were employed in the weekly chore of scouring front windowsills and doorsteps of terraced houses – their name arose from the original ‘Donkey Brand’ that bore an image of a donkey.

A donkey used for carrying loads on the island of Santorini

in September 1977

The donkey treadwheel at Carisbrooke Castle

The Tower of St Mary Magdalene’s Church at Taunton

The rebuilt tower of St Mary Magdalene’s Church, Taunton

On land and at sea, mechanical devices or engines were developed to reduce or replace the labour of both animals and people. The advent of steam power was transformative, and in Britain steam engines were first adopted in the early 18th century for pumping water from mines. In North America, the term ‘donkey engine’ or ‘steam donkey’ was commonly applied to the steam-powered winches employed in logging operations. ‘Donkey Riding’ was a popular shanty or work-song of the seamen and dockers in the timber ports, notably Quebec and Miramichi, and the reference to donkey riding may have related to the steam-powered winches. 3

Some of the large cargo-carrying sailing ships were actually faster than early steamships, and they could operate with a much smaller crew when equipped with a donkey engine and boiler to hoist the sails and operate auxiliary machinery such as bilge pumps, capstans, winches and cranes. When steamships were in port and the main boilers were not running, various tasks like pumping had to be done manually, unless donkey engines were fitted as auxiliary engines. Until the 1960s, most loading and discharging of ships involved a large amount of manual labour.4 The Engineer magazine was launched in January 1856, and from its second issue steam cranes were discussed being fitted to the screw colliers that transported coal to London from Newcastle and Sunderland: ‘The quantity of coals discharged by a gang of whippers is seldom more than 14 tons per hour, or by two gangs, say, 30 tons; whereas we have seen that from 60 to 80 tons can be delivered by two steam cranes in the same time.’5

The donkey engine might be housed in a structure on deck known as the ‘donkey house’, while the donkey boiler could be next to it or below decks near the main boilers and coal store. An example of a donkey engine running a pump at sea was on board the iron screw steamship Sarah Sands, which was chartered in 1857 by the East India Company to carry troop reinforcements to India to help suppress the Mutiny. The vessel left Portsmouth that August, bound for Calcutta (now Kolkata), but on 11 November, between Mauritius and Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), a fierce fire broke out in the hold. One report said that the crew ran out lengths of hose from the fire-engines, ‘while hose was also put on the donkey-engine’, and in a letter to his parents, Private Philip Folland mentioned that they had only two pumps on board to operate hoses, one being a patent hand pump and the other ‘a steam pump named the donkey pump, which was a very small one indeed’.6

In The Sailor’s Word-Book, posthumously published in 1867, Admiral William Henry Smyth gave a definition of a donkey engine: ‘An auxiliary steam-engine for feeding the boilers of the principal engine when they are stopped; or for any other duties independent of the ship’s propelling engines.’ 7 He was referring to the role of donkey engines in powering feed pumps that kept a steamship’s main boilers (which were under pressure) topped up with water. A few years earlier, William Rankine, the Regius Professor of Civil Engineering and Mechanics at Glasgow University, published a landmark textbook on steam engines, in which he also described this practice:

The feed-pumps are worked by the engine itself when it is in motion; but when it is standing still, and it becomes necessary to feed the boiler, they are driven either by hand, or by a small auxiliary engine called a ‘Donkey.’ For all marine boilers of considerable size, a donkey-engine is necessary. 8

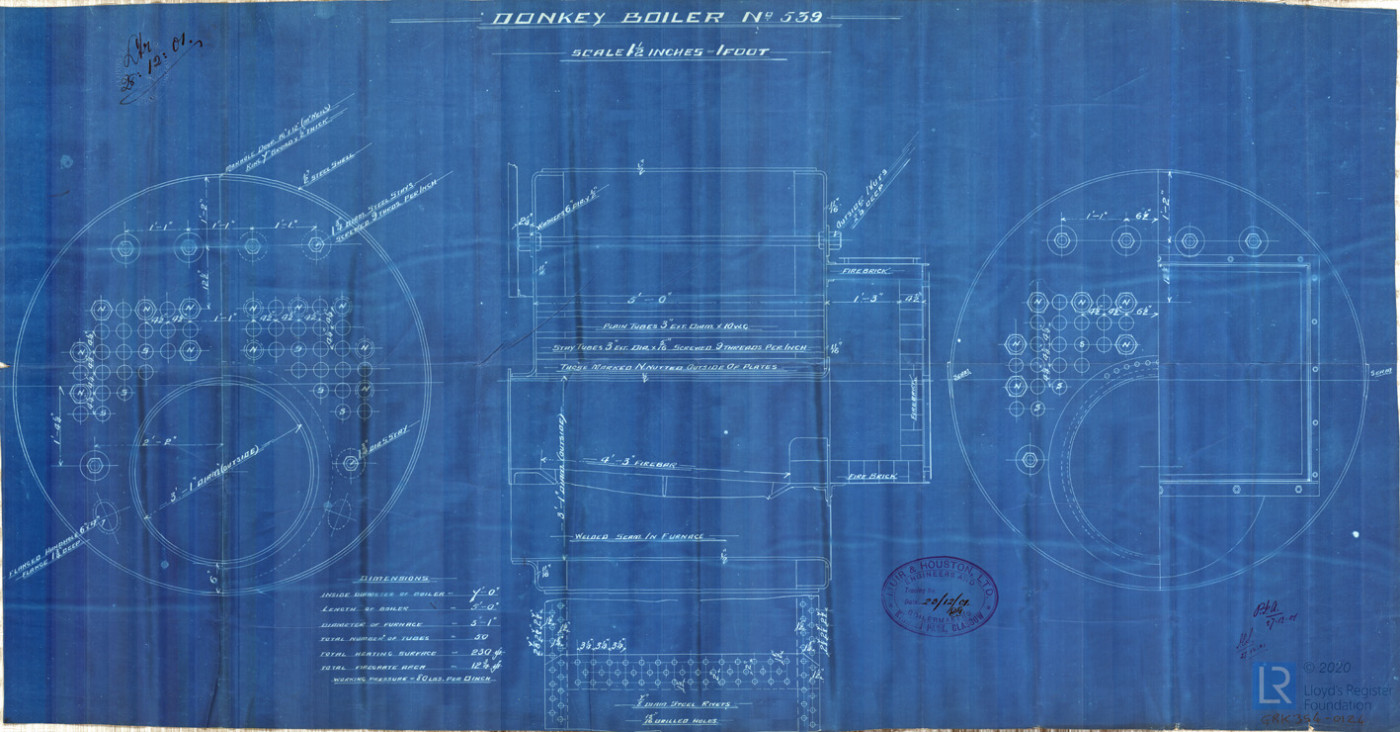

All steam boilers operated under pressure, which could be dangerous and lead to explosions, and although the boiler for a donkey engine was smaller than the main steamship boilers, accidents still proved devastating. Boiler safety was essential. The Mopsa was a steel screw steamer that was built in 1901–2 for the Bennett Steamship Company of Goole in Yorkshire at Port Glasgow’s Murdoch & Murray shipyard. Her two boilers were constructed by Muir & Houston in Glasgow, and a plan of the main boiler shows it to have had an inside diameter of 13 feet 3 inches, a length of 11 feet and a working pressure of 180 pounds to the square inch. The plan of the donkey boiler reveals measurements of 7 feet for the inside diameter, 3 feet 1 inch for its length and 80 pounds to the square inch working pressure.

In the Lloyd’s Register of Ships, the Mopsa was classed as ✠100A1. The Maltese cross prefix was introduced in 1853 to denote that the vessel had been constantly surveyed throughout construction under Lloyd’s Register (LR) Special Survey. 100A1 was the highest class for an iron or steel ship. In the early days of steam, LR surveyors relied on competent master engineers to produce reports of machinery, engines and boilers, adding MC (Machinery Certified) to the vessel’s name in the Register Books. In 1873, it was decided that the boilers and machinery of all steamships should also be constructed under Special Survey, and engineer surveyors began to be employed. 9 A red Maltese cross and the letters LMC showed that this happened with the Mopsa. 10 Nothing could protect the Mopsa from the hazards of war, and on 15 July 1916 she struck a mine off the Suffolk coast and sank. 11

Plan of Donkey Boiler for Mopsa

Wreckage of donkey engine explosion on the Valdivia

The steel-hulled Tijuca was built on the Tyne in 1886 as a passenger steamship by Armstrong, Mitchell & Co. She was registered in Hamburg, and a decade later her name was changed to the Valdivia, after which the 1898–9 German Valdivia Expedition was named that explored the deep oceans.

On 13 February 1907, this German vessel was travelling from Jamaica and Haiti to New York when a donkey boiler exploded. Considerable damage occurred and seven of the crew lost their lives, as was reported in the newspapers:

The donkey engine boiler exploded throwing the steamer’s funnel over and ripping open the upper deck. Seven men were instantly killed. The escaping steam enveloped the entire steamer, creating a scene of great confusion. The chief officer, who at the time was on duty on the bridge, was burned in the debris. He said when the explosion occurred everything appeared to fall over the bridge on the fore deck. All life boats were damaged. All inner structures abaft bridge were completely torn out.12

When the explosion occurred, the steamer stopped and everyone rushed to help, though the bodies were difficult to extricate as they were so mangled. It is hardly surprising, therefore, that they were buried at sea before reaching New York three days later.

Another example of the damage caused by a donkey boiler explosion occurred on 13 June 1935, when the Herzogin Cecilie was docked at Belfast. This was a greatly admired four-masted barque with a steel hull that had been built in Germany in 1902. She was one of the largest and fastest sailing ships, often used for carrying grain from Australia to Britain. The Scotsman newspaper reported two fatalities and two injuries:

TWO KILLED BY EXPLOSION

Donkey Boiler Blown from Ship on to Quay

Two Finnish sailors were killed at Belfast yesterday when a donkey engine boiler burst on the four-masted Finnish barque Herzogin Cecilie, which was discharging a cargo of wheat from Australia. James Cronghan, a dock labourer, of Park Street, Belfast, and Boris Lendholm, second mate of the ship were struck by splinters. They were taken to hospital.13

Damage also occurred to the Herzogin Cecilie: ‘The explosion blew the boiler through the main deck of the vessel 300 feet into the air and on to a wooden shed on the quay. A great gap was created in the deck of the vessel, which was strewn with wreckage.’

After repairs in Belfast and Nystad in Finland, the Herzogin Cecilie sailed to Copenhagen and was surveyed by Germanischer Lloyd, before setting out for Australia, where the vessel was loaded with more than 4,000 tons of wheat. Arriving at Falmouth in Cornwall on 23 April 1936, they set sail for Ipswich in Suffolk the following evening, in dense fog. Disastrous errors led to rocks being hit at Soar Mill Cove on the south Devon coast. After much of the cargo was discharged, the Herzogin Cecilie was refloated and towed to Starehole Bay, but was by now too badly damaged. Instead, the wreck was sold to a local scrap merchant, while news spread round the world of the fate of this once magnificent ship.14

Footnotes

-

1

Eric S. Wood 1995 Historical Britain: A comprehensive account of the development of rural and urban life and landscape from prehistory to the present day (London: The Harvill Press), pp. 546–7.

-

2

‘A Donkey on St. Mary’s Tower’ in Taunton Courier 13th December 1913, p. 10; Robin Bush 1983 Jeboult’s Taunton: A Victorian Retrospect (Barracuda Books, Buckingham), p. 50.

-

3

Stan Hugill 1969 Shanties and Sailors’ Songs (London: Herbert Jenkins), pp. 52, 201–3; Stan Hugill 1961 (revised 1984) Shanties from the Seven Seas: Shipboard Work-Songs and Songs used as Work-Songs from the Great Days of Sail (London, Boston, Melbourne and Henley: Routledge & Kegan Paul), pp.117–20. The shanty was based on ‘Highland Laddie’, and versions were also common with the cotton stowers. The meaning of ‘donkey’ is disputed, as the shanty may have used the donkey refrain before the era of donkey engines, though the English Folk Dance & Song Society (efdss.org) accepts the meaning: ‘The whispered quarter-note rhythms imitate the sound of the steam-powered, single-cylinder donkey engine’.

-

4

David MacGregor 2001 The Schooner: Its Design and Development from 1600 to the Present (London: Chatham Publishing; first published in 1997), pp. 82, 140, 154 (caption); Denis Griffiths 1997 Steam at Sea: Two centuries of steam-powered ships (London: Conway Maritime Press), pp. 85, 87; Michael Stammers 2007 The Industrial Archaeology of Docks and Harbours (Stroud: Tempus Publishing), pp. 89–108.

-

5

The Engineer vol. 1, 11th January 1856, p. 24; 7th March 1856, p. 120.

-

6

‘Burning of the Iron S.S. (transport) Sarah Sands’ in The Mercantile Marine Magazine and Nautical Record 5, February 1858, pp. 48–50; The North Devon Journal 18th February 1858, p. 8; Glanville J. Davies 1975 ‘The Wreck of the S.S. Sarah Sands: The Victoria Cross Warrant of 1858’ The Mariner’s Mirror 61 no. 1, pp. 61–71; Roger Willoughby and Alan Coles 2015 The Burning of the Sarah Sands (London: Savannah Publications).

-

7

W. H. Smyth 1867 The Sailor’s Word-Book: An Alphabetical Digest of Nautical Terms (London: Blackie and Son), p. 257. Smyth died in 1865.

-

8

William John Macquorn Rankine 1859 A Manual of the Steam Engine and other Prime Movers (London and Glasgow: Richard Griffin and Company), p. 464.

-

9

Nigel Watson 2010 Lloyd’s Register: 250 years of service (London: Lloyd’s Register), pp. 76, 103, 131–2; Nigel Watson 2015 Maritime science and technology: changing our world (London: Lloyd’s Register), p. 115.

-

10

Lloyd’s Register of British and Foreign Shipping. Volume 1: Steamers (1903/4) (London).

-

11

Hull Daily Mail 17th July 1916, p. 4; Portsmouth Evening News 7th July 1916, p. 3.

-

12

Hickory Democrat 21st February 1907, p. 4; Sheffield Daily Telegraph 18th February 1907, p. 7.

-

13

The Scotsman 13th June 1935, p. 16. See also Basil Greenhill and John Hackman 1991 The Herzogin Cecilie: The Life and Times of a Four-Masted Barque (London: Conway Maritime Press), pp. 157–8.

-

14

Greenhill and Hackman 1991, pp. 151–88.