The Cospatrick Disaster is a tragic story of human endurance and courage. It tells the story of the 1874 shipwreck of the Cospatrick, a clipper ship bound for New Zealand, which caught fire and sank in the mid-Atlantic Ocean.

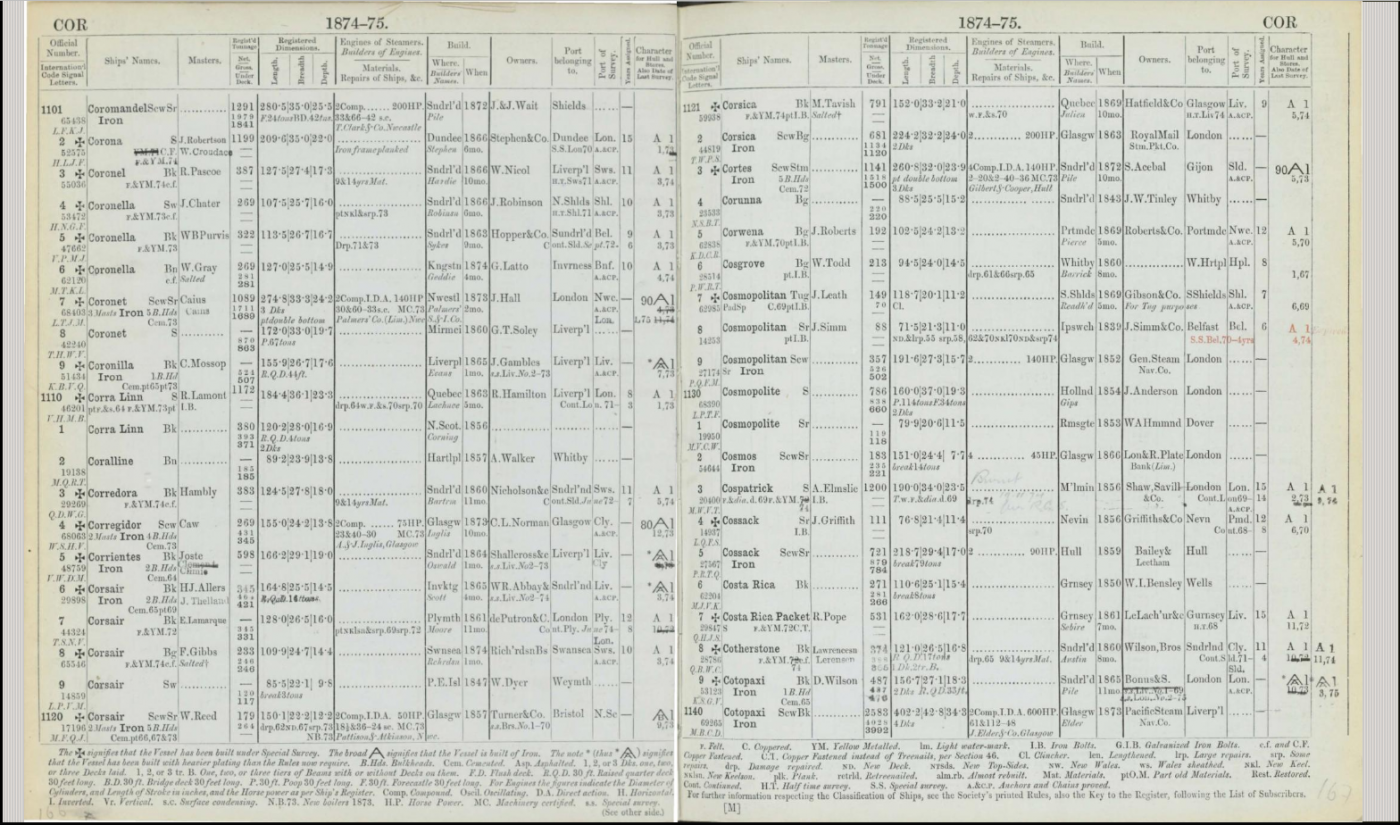

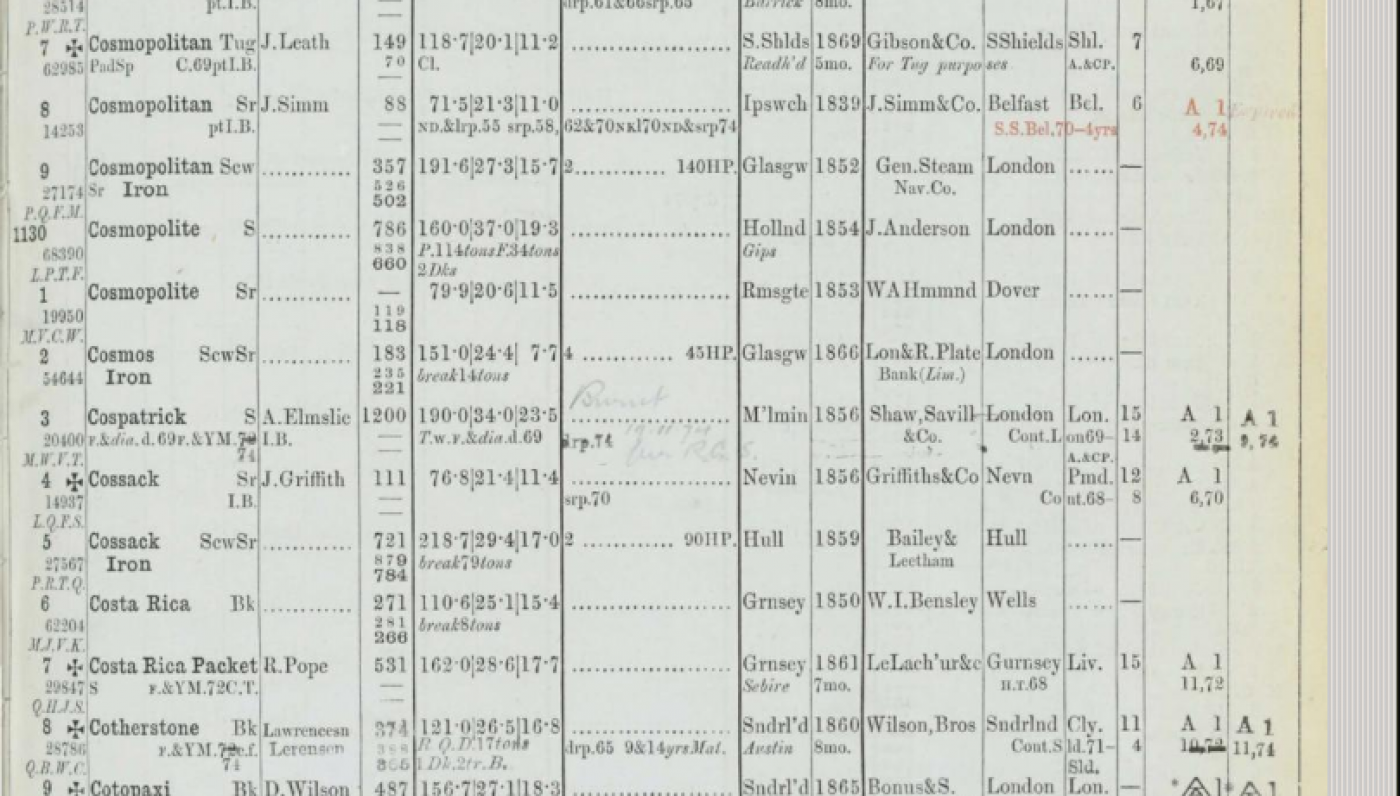

Many editions of the Lloyd’s Register of Ships have been digitised by the Heritage and Education Centre of the Lloyd’s Register Foundation and are freely available online. In the volume for 1st July 1874 to 30th June 1875, the entry for the Cospatrick has a rare handwritten annotation – a faint and enigmatic pencilled note that merely says: ‘Burnt 19.11.74 per R.G.S.’ This information came from the Registrar General of Shipping and Seamen (usually abbreviated to R.G.S.S.) and referred to a terrible disaster in November 1874 that had repercussions around the world – a tale of emigration, lengthy sea journeys, insecure cargoes, fires on board wooden sailing vessels, inadequate lifeboat provision and cannibalism.

The entry for the Cospatrick in the 1874–5 Lloyd’s Register of Shipping, with the pencilled annotation

The entry for the Cospatrick in the 1874–5 Lloyd’s Register of Shipping, with the pencilled annotation

Several East India companies once existed, such as the British, Dutch, French and Portuguese, and their sailing vessels – known as East Indiamen or Indiamen – traded with India, the East Indies and China via the Cape of Good Hope. By the 1830s in Britain, the trading monopoly of the Honourable East India Company was over, and fast merchantmen known as Blackwall frigates or Blackwallers began to replace the East Indiamen. These distinctive three-masted wooden sailing ships were initially built at the Blackwall shipyard on the River Thames in London, though other shipyards in Britain and beyond were later used.

The Cospatrick was a fine example of a Blackwall frigate, constructed of teak in 1856 at Moulmein (now Mawlamyine) in Burma. She was surveyed at London in September and October 1857 by Lloyd’s Register surveyors James Martin and Thomas W. Wawn, assisted by J.H. Tiltman, and was classed as A1.

Some 15 years later, the Cospatrick was purchased by the shipping company Shaw, Savill & Co for trade with New Zealand, and in February 1873 a survey for repairs was carried out for the new owners at London, with the vessel once again being classed as A1. 1

Four decades earlier, hundreds of thousands of workers had left Britain for North America and Australia because of an agricultural depression, but in the 1870s an even worse depression occurred. In part this was due to a run of wet summers and poor harvests, but it was mainly caused by cheaper shipping costs and the dropping of tariffs.

Consequently, huge quantities of grain were imported from the newly settled North American prairies and the steppes of Russia, undercutting Britain’s farmers. New Zealand now became attractive, because in the 1870s that country was actively encouraging new settlers with assisted or free passage.

The first voyage by the Cospatrick was to Otago in New Zealand and took 108 days, arriving on 6th July 1873 and carrying mainly cargo, as well as 37 adult emigrants. The immigration officer at Dunedin did an inspection: ‘The immigrants expressed themselves as fully satisfied with their treatment, and speak well of the Surgeon, Superintendent, Captain, and officers of the ship ... The accommodation was good, and appeared very clean and very comfortable.’ 2 He added that the captains and officers were entitled to the gratuities owing to them, but also voiced his concern: ‘It is not desirable that a few immigrants, as in this case, should be sent in a heavily laden vessel, not subject to the provisions of the Passenger Act.’

The Cospatrick continued to Australia, India, St Helena and South America, before returning to the port of Gravesend in Kent in late June 1874. 3 The vessel then prepared to go back to New Zealand, leaving Gravesend on 11th September, the start of another lengthy non-stop passage.4

On board were at least 41 crew and some family members, 4 paying passengers and many emigrants – 429 in all, a mixture of families, married couples and single men and women from all over Britain, Ireland and even Jersey. Most were labourers, agricultural workers and servants from inland counties, who had probably never before set eyes on the sea. 5

The Cospatrick Blackwall frigate at Port Chalmers, New Zealand, in July or August 1873

The Cospatrick set sail from Gravesend in Kent on 11th September 1874

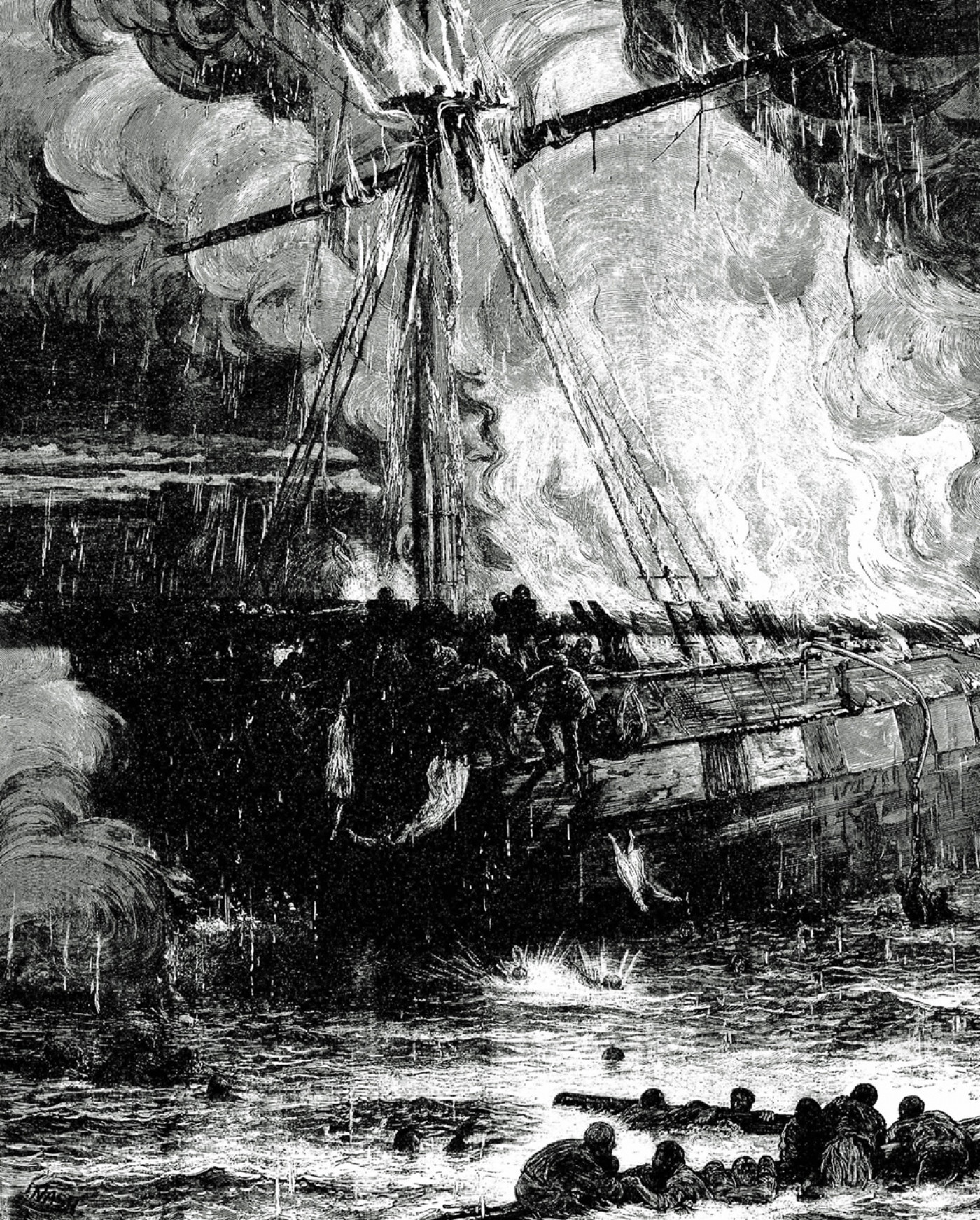

The Cospatrick on fire

The first two months of the voyage were uneventful, and by 17th November they were roughly 400 miles south-west of Cape Town. Charles Henry Macdonald, originally from Montrose in Scotland, was the Cospatrick’s second mate (officer), and a little after midnight he was woken by the fire alarm:

I ran forward and saw the chief mate getting the men to work the force pumps. All the passengers were rushing on deck, and smoke was coming out of the fore scuttle . I ran aft to report this to the captain and to put my clothes on, as I had nothing on at that time. When I went forward again they were playing the hose down the fore scuttle. 6

Captain Elmslie told Macdonald to try to locate and extinguish the fire, but soon the blaze was out of control.

Eventually, Elmslie ordered everyone to save themselves. This turned into a free-for-all, because there were insufficient lifeboats and no concept of ‘women and children first’. Ships traditionally carried open boats with oars on their decks for tasks such as ship to shore communication. Lifeboats were seen as an encumbrance. The Cospatrick’s six boats complied with the latest legislation, which made lifeboats compulsory for vessels carrying passengers, though their provision was based on the ship’s tonnage.

By now two of the Cospatrick’s boats were on fire, the starboard lifeboat had capsized, drowning dozens of women, another proved impossible to launch and the fate of the captain’s gig was unknown. Only the port lifeboat was successfully lowered, just as the foremast went over the side.

Macdonald and others jumped in, and some crew and passengers also managed to swim to the boat and clamber aboard. After rowing a short distance away, the survivors watched the Cospatrick’s mainmast come crashing down, and then the stern exploded. Another boat nearby – the righted starboard lifeboat – had no oars or officers, so Macdonald agreed to take charge. These two boats were crammed full with 62 survivors from the crew and passengers. For two days they stayed by the burning ship, powerless to help those clinging to the wreckage.

Once the Cospatrick sank, the two boats headed in the direction of the Cape of Good Hope, without any compass, food, water, masts or sails. Initially they kept close together, but in heavy seas on the 22nd, the port lifeboat disappeared. From then on, those in the starboard lifeboat struggled to survive. One man fell overboard and drowned, and three died from drinking sea water.

Being so desperate as more men died, everyone resorted to cannibalism, which Macdonald later recorded: ‘Four more men died the same way as the others, and we were that hungry and thirsty that we drank the blood and ate the livers of two of them. That day we lost our only oar. On the next day it blew a gale ... There were six more deaths that day.’ 7

As each day passed, more deaths occurred: ‘On the 27th it was squally all round with light showers, but we never caught a drop of water, although we tried to do so. Two more died that day. We threw one overboard, but we were too weak to throw over the other. Only five were then left.’ Suddenly, while they were all dozing, a ship was spotted nearby. This was the British Sceptre, an iron sailing vessel heading to Dundee from Calcutta (Kolkata) with a cargo of jute. Her crew had noticed a trail of wreckage from a recent shipwreck and so were looking out for survivors. ‘We received every kindness on board the British Sceptre,’ Macdonald commented. ‘I was very ill on board, almost down to death’s-door. While in the boat I did not drink any salt water, excepting a mouthful now and then’ – further evidence of cannibalism.

Two of the rescued men died as the British Sceptre sailed towards the island of St Helena. Here, the three sole survivors were transferred to the mail steamship Nyanza, which took them back to England – Charles Macdonald, the second mate, Thomas Lewis, an able seaman from Anglesey, and Edward Cotter, 18 years old and an ordinary seaman. On the last day of 1874 they were landed at Plymouth, 104 days after abandoning ship. Everyone else had perished – almost 500 people.

A Board of Trade Inquiry was held at Greenwich Police Court from 3rd to 5th February 1875 to investigate the cause of the disaster, though the vessel itself was not being scrutinised, as she was agreed to be a fine ship.8 After hearing from various expert witnesses, the Inquiry dismissed the original theory of the fire starting in the boatswain’s locker, because it had spread far too quickly.

Instead, it concluded that one or more crew members or emigrants must have found a way into the insecure hold below the main deck, because ‘sailors do not yield to emigrants in their keenness of research for the means of intoxication’. Faced with the extreme boredom of such a long journey, the alcohol in the hold would have been a temptation – 184 barrels of beer, 5,732 gallons of spirits and 1,488 gallons of wine. A naked flame from a candle or match most probably set fire to some material like straw, and as the cargo also contained 1,732 gallons of linseed oil, 40 cans of other oil and materials like turpentine, paraffin, paint, candles and varnish, with tons of coal nearby, there was soon an uncontrolled inferno.

Such plunder of alcohol was known to have occurred on other emigrant ships and so should have been prevented. It was also obvious from the Inquiry that other factors were equally to blame, including the way the cargo was loaded, the lack of fire drills and the lamentable though legal provision of lifeboats, which at best would have saved only one-third of the people on board.9

The loss of the Cospatrick was closely followed in New Zealand. As soon as the full extent of the disaster was known, a relief fund opened in London, and the New Zealand Government pledged £1,000. The money was distributed to relatives just over two months later, as the newspapers reported:

A meeting of the Committee charged with the distribution of the fund raised in the City of London towards the relief of the few survivors and the dependent relatives of the passengers and crew who perished with the ill-fated emigrant ship Cospatrick, during a voyage to New Zealand, was held at the Mansion House yesterday ... the whole amount at the disposal of the Committee after payment of expenses was 3050l. Of that sum 2700l. in all was awarded to those whose claim for relief on the fund had been recognised by the committee, leaving a balance in hand of about 350l. at their disposal to meet contingencies.10

The largest shares went to the relatives of the captain and crew, with far smaller amounts to families of the emigrants: ‘The Committee awarded 500l. to the two orphan daughters of Captain Elmslie, who perished with the vessel; 865l. among the near and dependent relatives of those of the crew who were lost, and the remainder among the surviving and more or less dependent relatives of the passengers who perished.’ At another Committee meeting five months later, it was decided to distribute the remaining money and close the fund.

The impact of the disaster, with its massive loss of life, was felt far and wide. At Shipton-under-Wychwood in Oxfordshire, 17 members of the inter-related Hedges and Townsend families perished, and money was raised in the parish for a commemorative monument. In Jersey, another monument was erected in memory of those who had drowned.11 Single commemorative gravestones included one for five members of the Thomson family in the churchyard at Killean in Argyll, Scotland.

Members of the Hedges and Townsend families who died in the Cospatrick are commemorated in this monument

On the village green at Shipton-under-Wychwood, Oxfordshire, with a plaque to the Hedges

Gravestone of the Goodere family at the Higher Cemetery in Exeter, Devon.

Here and there, family gravestones include the name of a Cospatrick victim. In the Higher Cemetery at Exeter in Devon, a gravestone inscription records the death in May 1874 of Charles Elisha Goodere, aged 18 years, followed by the words: ‘Also of William Goodere who was lost in the Cospatrick November 17th 1874 aged 21 years, deeply lamented’.

These were the two oldest sons of George Goodere (a boot and shoe maker) and his wife Jane. Their large family lived in Exeter’s city centre. Charles had been a mathematical instrument maker, while William was a carpenter. For some reason, he decided to emigrate to New Zealand a few months after his brother’s death. The names of their father and mother, who died in 1900 and 1905, were later added to the monument. Such a nondescript gravestone conceals a very poignant story.

The tragedy of the Cospatrick became widely known and was then quietly forgotten, but for most lost ships, their fate would forever remain a mystery.

Footnotes

-

1

David Savill 1986 Sail to New Zealand: The Story of Shaw Savill & Co 1858–1882 (London: Robert Hale)

-

2

Immigration to New Zealand (further memoranda to the agent-general). Appendix to the Journals of the House of Representatives, 1873, session 1, pp. 3–4 (12th July 1873).

-

3

Lloyd’s List 27th June 1874, p. 9.

-

4

Lloyd’s List 14th September 1874, p. 5.

-

5

Many details are discussed in Charles R. Clark 2006 Women and Children Last: The Burning of the Emigrant Ship Cospatrick (Otago University Press).

-

6

Two versions of Macdonald’s account are given in The Times 1st January 1875, pp. 9–10. See also Illustrated London News Saturday 16th January 1875, p. 61.

-

7

The Times 1st January 1875, p. 10.

-

8

The Times 6th February 1875, p. 12.

-

9

The Times 22nd February 1875, p. 10.

-

10

London Evening Standard 10th March 1875, p. 3.

-

11

See Mark Boleat 2019 Migration from Jersey to New Zealand in the 1870’s (London), pp. 28–9.