The pride of the Royal Navy, the 100-gun Royal George, sank at Spithead on 29 August 1782. ‘The Sinking of the Royal George’ story is told here. That was not the end of the story, because the wreck was a hazard in the middle of a busy shipping lane. For 60 years, it was the scene of salvage and diving innovation, with diving bells, early diving helmets, explosions and even souvenirs.

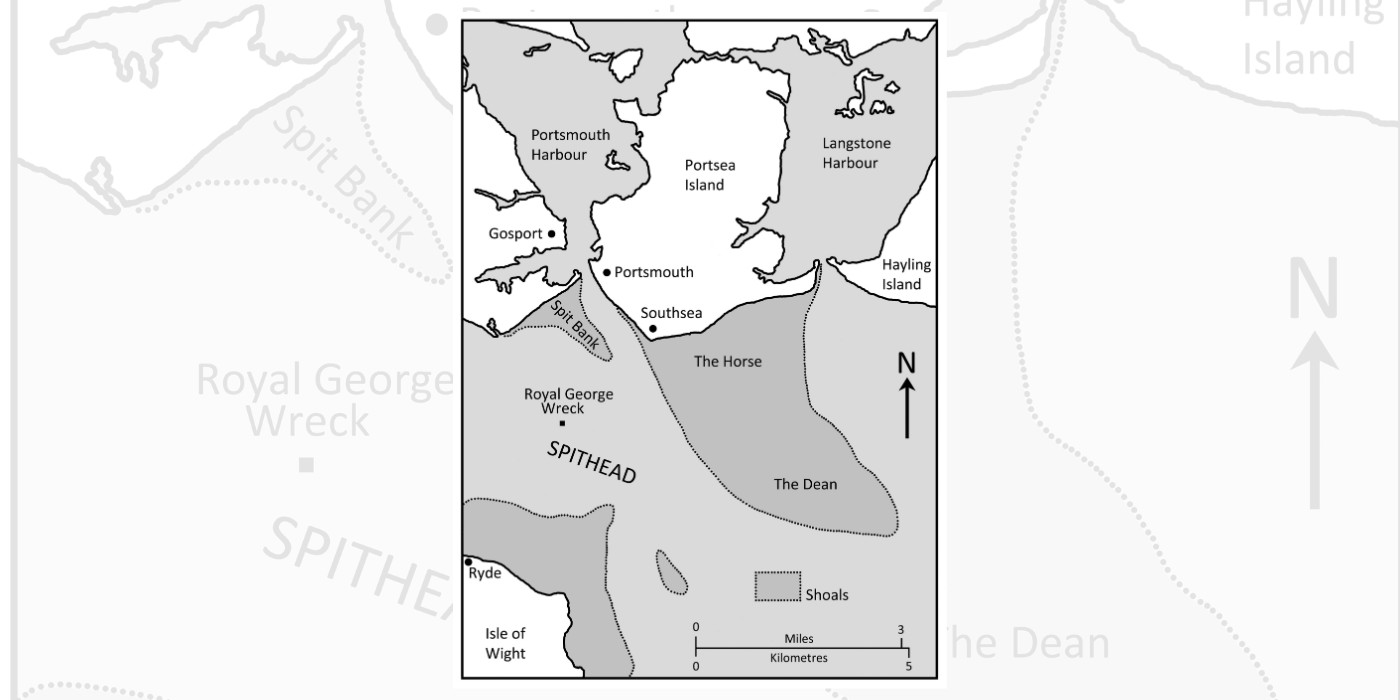

Spithead is the stretch of water between the Isle of Wight to the south and Gosport and Portsmouth Harbour to the north. This was an especially important anchorage in the days of sailing ships, shielded from the English Channel and the worst of its weather. The name derives from the Spit Bank sandbank (usually called Spit Sand today) that extends from the west side of the harbour entrance. The artist Clarkson Stanfield (1793–1867), known for his marine paintings, wrote in 1836:

The roadstead is called the Spithead, and marked out by buoys at regular intervals, and is often the spot chosen for the assembling of the English fleet. The port is the general rendezvous where all ships homeward or outward bound take convoy, and frequently seven hundred merchantmen have sailed at one time from Spithead.1

The position of the Royal George wreck at Spithead

Approximate position of the site of the Royal George wreck looking towards the Isle of Wight

It was here in August 1782 that a convoy of merchant vessels and transports and the protecting warships of the Channel Fleet were assembled before sailing to relieve the siege of Gibraltar. Among them was the Royal George, laden with provisions for six months. Suddenly, due to a relatively insignificant repair going horribly wrong, the Royal George fell sideways and sank, taking the Lark sloop victualler as well. Hundreds of people lost their lives.2

The hull of the Royal George quickly reverted to an upright position, so the huge masts were visible above water. A 1:48 scale model of the Royal George, without masts and rigging, is in the National Maritime Museum at Greenwich. It can be viewed in a video made for Lloyd’s Register Foundation’s programme of ‘Maritime Innovation in Miniature’ and gives an idea of the enormity of the shipwreck.

A considerable number of vessels of all sizes used Spithead. On one single day three months before this disaster, the Hampshire Chronicle recorded about 60 vessels arriving at Portsmouth and 11 sailing, while about 13 arrived at Cowes and 29 sailed.3 Shortly after the sinking, the Grenville Post Office packet ship passed the wreck and anchored near the Isle of Wight. One of her seamen, Samuel Kelly, said: ‘our ship lay off Ryde, exactly in the stream of ebb that came from the wreck, we had therefore an opportunity of seeing the dead in vast numbers floating by us’. 4

A buoy soon marked the hazardous wreck, but it was feared that a sandbank would build up and become a dangerous shoal. One newspaper speculated: ‘if she was allowed to remain, she would in time form a bank that would occupy the anchorage of eight ships of the line, and be an infinite detriment to the road of Spithead’. 5

The use of diving bells for salvage goes back to the early 16th century. In effect, they were inverted barrels made from wood and metal. From the 1660s members of the Royal Society undertook diving bell experiments, including the astronomer Edmond Halley, who devised a method of replenishing the air supply. Decades later his design was improved by Charles Spalding in Scotland, and when the Royal George sank, his own brother Thomas Spalding happened to be a surgeon on board the Winterton East Indiaman that was waiting at Spithead for the convoy to sail. 6

Thomas Spalding advised the Admiralty to construct a diving bell at Portsmouth Dockyard, based on his brother’s design. On 6th September 1782 he did a trial descent in this bell, as one newspaper related: ‘Mr. Spalding, surgeon of one of the Indiamen at Portsmouth, completed his diving bell, and went down on Friday evening to try it in the harbour, where he remained thirty-seven minutes under water, and found it answered perfectly well.’7 The next day Spalding made the first of several dives on the wreck, and Samuel Kelly visited the vessel from which he was working:

The principal bell, in which was a surgeon of an East Indiaman, with a Lascar (native of Bengal) was very large, made like a porter vat , the largest end downward. Round this a quantity of pig lead was fastened on, to sink it, there were small round glass windows to admit light near the top, and a large hole in the bottom for men to enter, under which a board was hung with chains, on which the men stood. 8

The diving bell used by Thomas Spalding in 1782

Model of the Royal George

Kelly was fascinated by this contraption: ‘On sinking the bell the water rose within, as far as the air pent up would let it, which might be about breast high on the men. In this small space of air they breathed.’ He observed how air to the divers was replenished:

Two smaller bells were employed to go up and down in succession to supply the large one with fresh air. At the top of each a leather hose was fixed. At the end of the hose was a brass cock, which, when sunk, was pulled into the large bell by a line; they then let in the fresh air, and the foul air returned in its place into the small bell, when it was hauled up again above the surface of the water, to let out the foul air and to fill again with fresh.

It was possible, Kelly learned, to explore the wreck: ‘The Lascar went out of the bell to inspect the situation of the things on deck, and received air from the bell by means of a leather hood covering his head with a hose to the air in the machine.’ 9

On 11 September 1782 the huge relief convoy sailed for Gibraltar, along with numerous other ships, including the Winterton. Thomas Spalding had been unwilling to stay behind and relinquish his post as Surgeon, but his brother Charles took over the salvage work on the Royal George until the winter, as reported by the Hampshire Chronicle: ‘The vessel, with the diving bell, which has been for some time employed about the Royal George, is come into harbour, with 16 guns, cordage, &c. saved, it being now too cold under water to do any further business this winter.’ 10

William Tracey, a Portsmouth ship broker, had meanwhile drawn up plans to raise the Royal George and Lark, which were accepted by the Admiralty. He embarked on the project in May 1783, after being promised considerable assistance, including the provision of ships, but from the outset he faced obstruction from Portsmouth Dockyard officials, especially Joseph Gilbert, the new Master Attendant. It took over a month before two ships, Diligente and Royal William, sailed from Portsmouth and into position either side of the wreck’s masts. 11

First of all, Tracey needed to shift the submerged Lark, which had been lashed to the Royal George while unloading casks of rum. His attempt to place a cable beneath the hull proved impossible owing to the quantity of sand that had already accumulated. Instead, cables were passed around the sides and made secure, forming a cradle. He then managed to raise the Lark off the sea bed in July and tow the vessel a considerable distance to shallow water near Haslar hospital. 12

Tracey decided to use the same method for the Royal George, but was thwarted by the dockyard. Even so, in early October the warship was moved 30 feet westwards. If the dockyard had been cooperative, the Royal George could probably have been successfully salvaged, but severe south-easterly gales now set in, halting the operation. Throughout the winter, Tracey paid to maintain the two navy ships and their crews. By the time he was ready to resume work, in May 1784, the Admiralty said that they would no longer support him, most likely because it was inconvenient to have the court martial findings disproved. Tracey was financially ruined. The London hydraulic engineer John Braithwaite was instead brought in to carry out salvage. Some cannons, smaller objects and an anchor were retrieved that summer, as well as the cables that Tracey had placed around the hull, but no attempt was made to raise the ship. 13

For several years little further work was done on the wreck, which remained a hazard. In 1796 the former Master Attendant of Portsmouth Dockyard, William Nichelson, published A Treatise on Practical Navigation and Seamanship. For vessels coming into Spithead, he warned that the masts of the Royal George were still standing and served as a beacon. A red buoy also marked the wreck. 14 When the foreman of the dockyard examined the wreck from a diving bell in June 1817, he found that a great deal of the upper structure had gone.

Salvage work finally resumed in 1832, exactly half a century after the sinking of the Royal George. By now, diving equipment was much improved, with diving helmets and an open dress superseding diving bells. Nearly a decade earlier, Charles Deane, a ship caulker, had filed a patent for a smoke helmet and garment for fighting fires.15 The copper helmet had a long leather pipe attached to a bellows, and a few were manufactured by the engineer Augustus Siebe, one of which was converted to underwater use by Charles and his brother John (who was a diver). They then began to earn a living from salvage. After an inspection dive on the Royal George, they received permission from the Admiralty in October 1834 to work there, using a long ladder to go to and from the wreck. Julian Slight, a Portsmouth Surgeon, described the equipment used by Charles:

His dress was composed of Indian rubber, made perfectly water-tight, having an helmet of metal on his head, extending to his shoulders large enough to allow him to turn his head round at pleasure, having three glass lenses to admit light, and a tube of the same flexible materials on the top to supply air by means of an air pump, worked by men in attendance from above. Mr. Dean (e), by this simple dress, although he had attached to him near 90lbs. weight to make him sink, readily walked about the ship. 16

A print showing Charles Deane at the bowsprit of the Royal George , August 1832

A commemorative plaque on a brass gun of the Royal George

Over the course of three years, Charles Deane recovered 30 cannons, described as ‘19 brass twenty-four pounders, 3 brass eighteen pounders, and 8 iron thirty-two pounders, all in a high state of preservation’. He also retrieved numerous smaller items, many of which were displayed in June 1835 at a Royal Submarine Exhibition in Regent Street, London. The next year John Deane recovered a cannon from an area close to the Royal George, ‘a brass 24- pounder gun, 11 feet long, loaded with one shot’. Its Latin inscription showed it was from Henry VIII’s ship Mary Rose that had sunk in 1545, pinpointing the wreck for the first time. 17 Eventually, that ship would be raised and preserved, but the Royal George was about to be blown up.

Colonel Charles William Pasley of the Royal Engineers at Chatham had experience of clearing wrecks with explosives in the River Thames, and he was now authorised to deal once and for all with the Royal George, which was still marked as a hazard by a red buoy. A small batch of explosives was fired on 29th August 1839 to coincide with the 57th anniversary of the shipwreck. There followed a constant round of placing an explosive charge in position, firing it and sending divers down to salvage anything, including parts of the ship. 18

Virtually everything had to be retrieved by divers, as Pasley explained in a letter to The Times in November: ‘No part of the Royal George ever rose to the surface after our explosions, except some large fragments of the mainmast, which were immediately recovered by the boats.’ In the first three months, the immense number of items included ‘12 guns, 5 guncarriages, 100 beams and riders, or large fragments of them, exclusive of other timbers, planks, and copper, besides the cooking-place and boilers complete, the stem, and a great part of the bows on each side of it, the two capstans, part of the mainmast, and all that remained of the foremast of the Royal George’. 19

Diving helmets were only loosely attached to the dress, and if a diver fell over, his helmet could fill with water. In 1840 Pasley began to use a much safer closed diving dress or suit made by Augustus Siebe, which also meant that divers could dispense with ladders. 20 For three more years the Royal George was systematically dismantled, including the removal of the ballast, coal, 80 feet of the keel and much of the bottom planking with its copper sheathing, along with numerous personal items, from shoes to candles. By September 1843 Pasley considered that the site was safe for shipping, and nowadays it is difficult to imagine the disaster that occurred there.

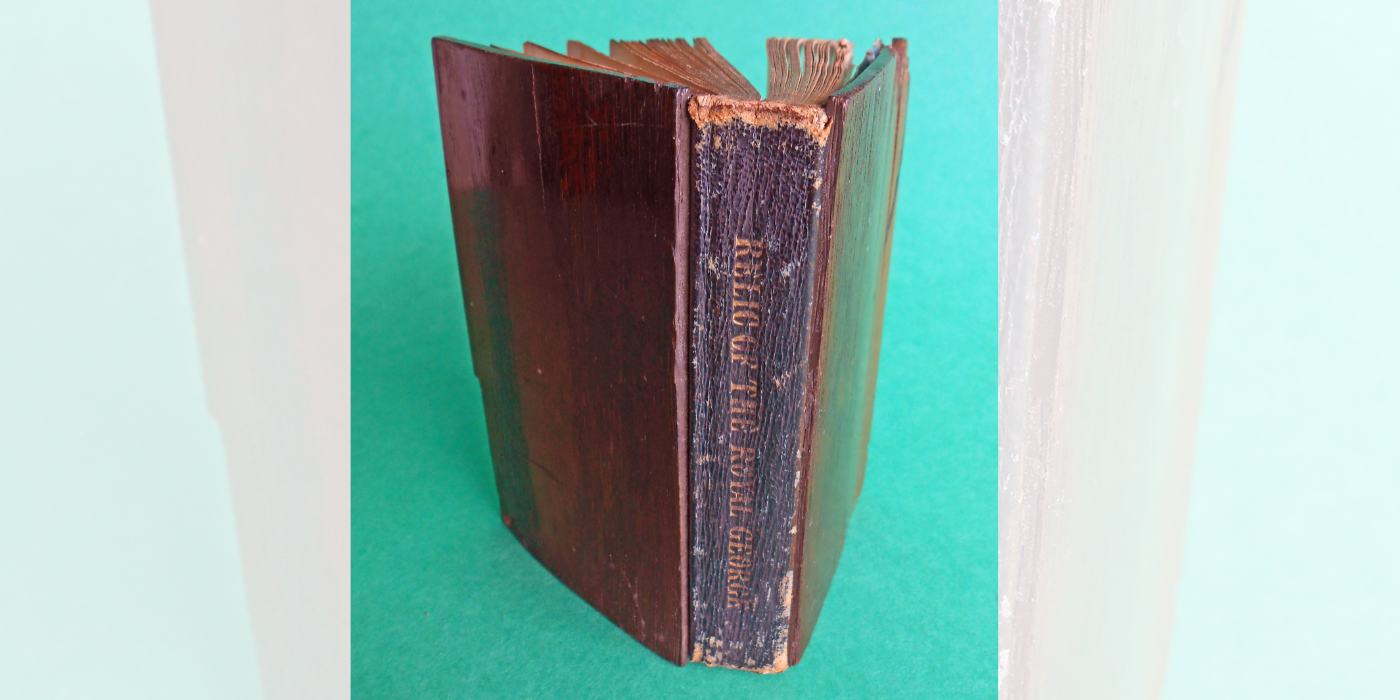

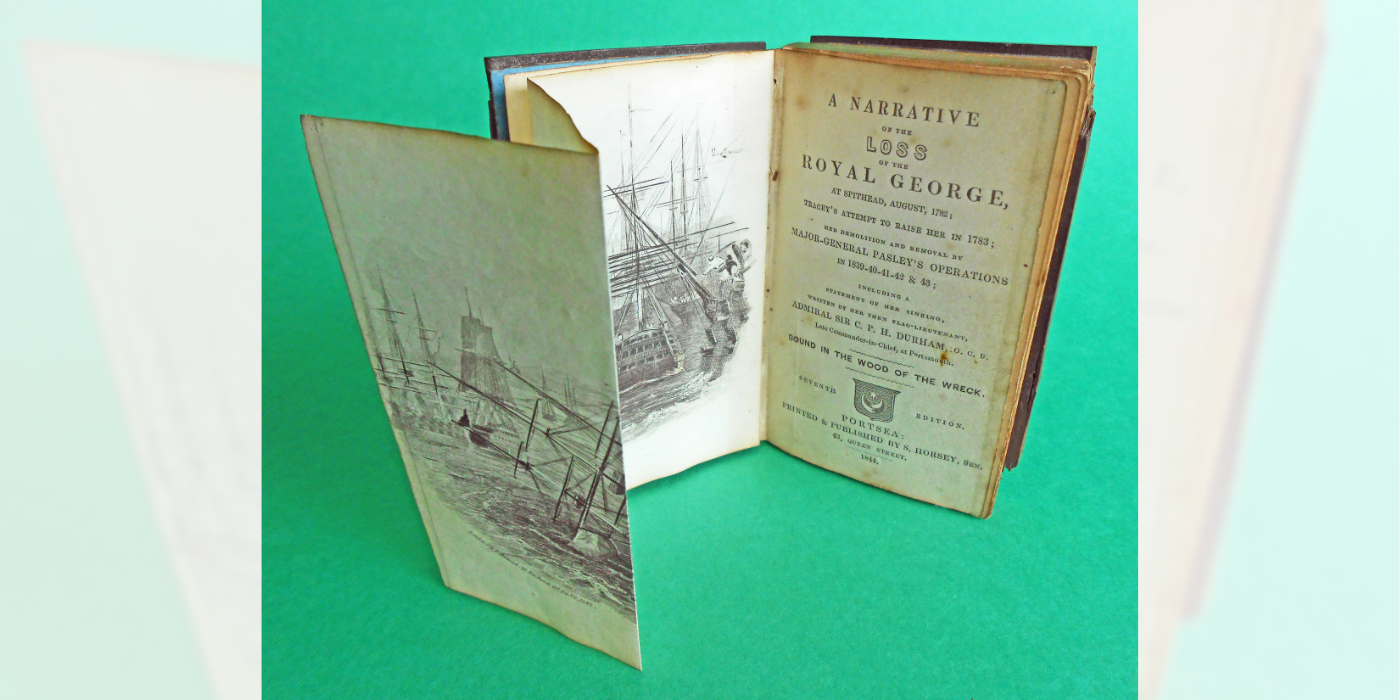

Some of the better items salvaged from the wreck found their way into museums and private collections. Pieces of the timber and metal were sold by the dockyard and turned into souvenirs such as snuff boxes, larger boxes and even cutlery. In 1840, a miniature book (4¼ inches high) was published at Portsea, with wooden covers made from salvaged timbers. It proved so popular that several editions were produced. 21

7th edition of A Narrative of the Loss of the Royal George , 1844

Inside view of the miniature book A Narrative of the Loss of the Royal George

Written in November 1840 and printed at the end of the book was ‘Lines on Receiving a Piece of the Wreck of the Royal George’ by William Holloway, best known for his poem about the 1786 wreck of the East Indiaman Halsewell. The Royal George poem begins:

Poor fragment of a mighty structure–won

From thy dark charnel-house beneath the wave;

There thou with human bones hast made thy bed

Fifty-eight summers, in thy watery grave.

Footnotes

-

1

Clarkson Stanfield 1836 Stanfield’s Coast Scenery: A series of views in the British Channel (London: Smith, Elder and Co), p. 30.

-

2

For the story of the siege of Gibraltar, see Roy and Lesley Adkins 2017 Gibraltar: The Greatest Siege in British History (London: Little, Brown; New York: Viking).

-

3

Hampshire Chronicle 3rd June 1782, p. 2.

-

4

Crosbie Garstin (ed.) 1925 Samuel Kelly: An Eighteenth Century Seaman (London: Jonathan Cape), p. 62. The Grenville was recently renamed the Shelburne, and Captain Samuel Bull, who Kelly refers to as Captain B, was only appointed on 14th August. See John Beck 2009 A History of the Falmouth Packet Service 1689–1850: The British Overseas Postal Service (South West Maritime History Society monograph 5), pp. 249, 282.

-

5

Caledonian Mercury 14th September 1782, p. 2.

-

6

Eugene Fairfield MacPike (ed.) 1932 Correspondence and Papers of Edmond Halley (Oxford: Clarendon Press). For the early history of explorers underwater, see Jeff Maynard 2023 The Frontier Below: The Past, Present and Future of our Quest to Go Deeper Underwater (London: William Collins).

-

7

Caledonian Mercury 14th September 1782, p. 2.

-

8

Garstin 1925, p. 61.

-

9

Garstin 1925, p. 62.

-

10

Hampshire Chronicle 25th November 1782, p. 3.

-

11

William Tracey 1785 A Candid and Accurate Narrative of the Operations Used in Endeavouring to Raise His Majesty’s Ship Royal George, In the Year 1783 (Portsmouth: W. Mowbray), pp. ii–iii, 1–14, 69.

-

12

Jackson’s Oxford Journal 19th July 1783, p. 1; Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette 24th July 1783, p. 2; Tracey 1785, pp. 10, 74–5.

-

13

Tracey 1785, pp. 11–22, 40–64, 85, 93–9; R.F. Johnson 1971 The Royal George (London: Charles Knight), pp. 143–4; Hilary L. Rubinstein 2020 Catastrophe at Spithead: The Sinking of the Royal George (Barnsley: Seaforth), pp. 194–8.

-

14

William Nichelson 1796 , A Treatise on Practical Navigation and Seamanship (London), p. 17; John Stephenson 1799 (2nd edn) The New British Channel Pilot (London), p. 35.

-

15

The London Journal of Arts and Sciences 9 (1825), pp. 341–4.

-

16

Julian Slight 1842 A Narrative of the Loss of the Royal George (Portsea: S. Horsey), pp. 77–8.

-

17

Slight 1842, p. 78; Morning Post 8th June 1835, p. 6.

-

18

J.W. Norie 1839 (11th edn.) The New British Channel Pilot (London: J.W. Norie and Co.), p. 41; see pp. 72 and 81 of ‘Colonel Pasley’s operations at Spithead, with a view to the demolition and removal of the wreck of the Royal George’, in The United Service Journal (1840, pp. 72–83); see p.153 of ‘Colonel Pasley’s operations at Spithead, with a view to the removal of the wreck of the Royal George’, in The United Service Journal (1840, pp. 149– 64). In 1812 Pasley founded the Royal Engineer Establishment at Chatham for training engineer soldiers.

-

19

The Times 19th November 1839, p. 5.

-

20

See Maynard 2023, pp. 70–4 and also pp. 673–4 of ‘Under the Sea’ in The Cornhill Magazine 17 (1868). Siebe went on to produce diving helmets and diving equipment, and his firm developed into Siebe Gorman and Company, well known for underwater equipment.

-

21

See Rubinstein 2020, pp. 204–19, for the artefacts recovered by Pasley and the souvenirs produced.