On 29 August 1782, the 100-gun warship Royal George, sunk whilst lying at anchor off Spithead and was Britain’s worst shipwreck until the Titanic over a century later.

Authors of history books are seldom short of ideas, but publishers may not share their expectation of commercial success. One of our ideas that went nowhere was about the sinking of the Royal George, but years later, when writing Gibraltar: The Greatest Siege in British History, we realised that these extraordinary stories were connected.1

On the morning of 29 August 1782, a series of errors led to the loss of the Royal George and the Lark sloop victualler at Spithead, the safe anchorage between Portsmouth and the Isle of Wight. It sent shockwaves far and wide. Hundreds of people perished in a matter of minutes, and it was Britain’s worst shipwreck until the Titanic over a century later. The story revolves around the protection of merchant convoys, too much hurry, poor leadership, poor seamanship, key officers absent ashore and (most surprising) large numbers of prostitutes and traders on board, all set against a background of the American Revolution and the Great Siege of Gibraltar.

Model of the Royal George

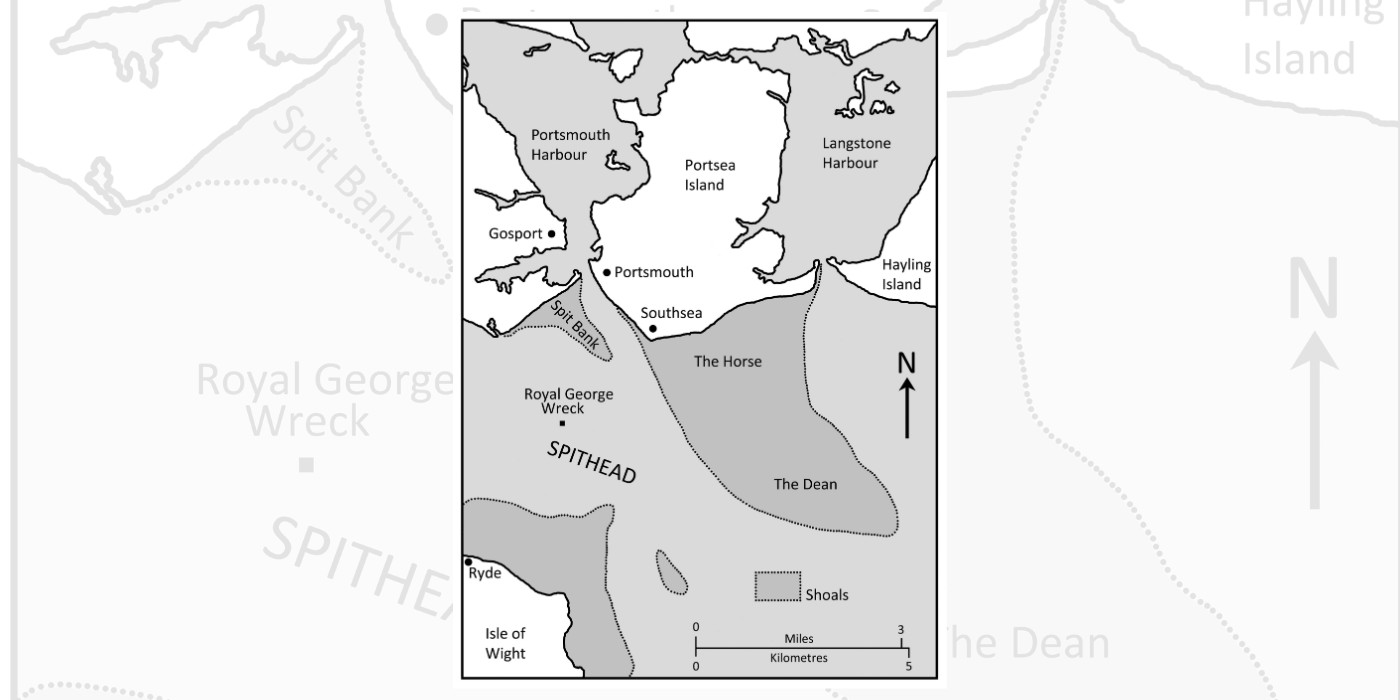

The position of the Royal George wreck at Spithead

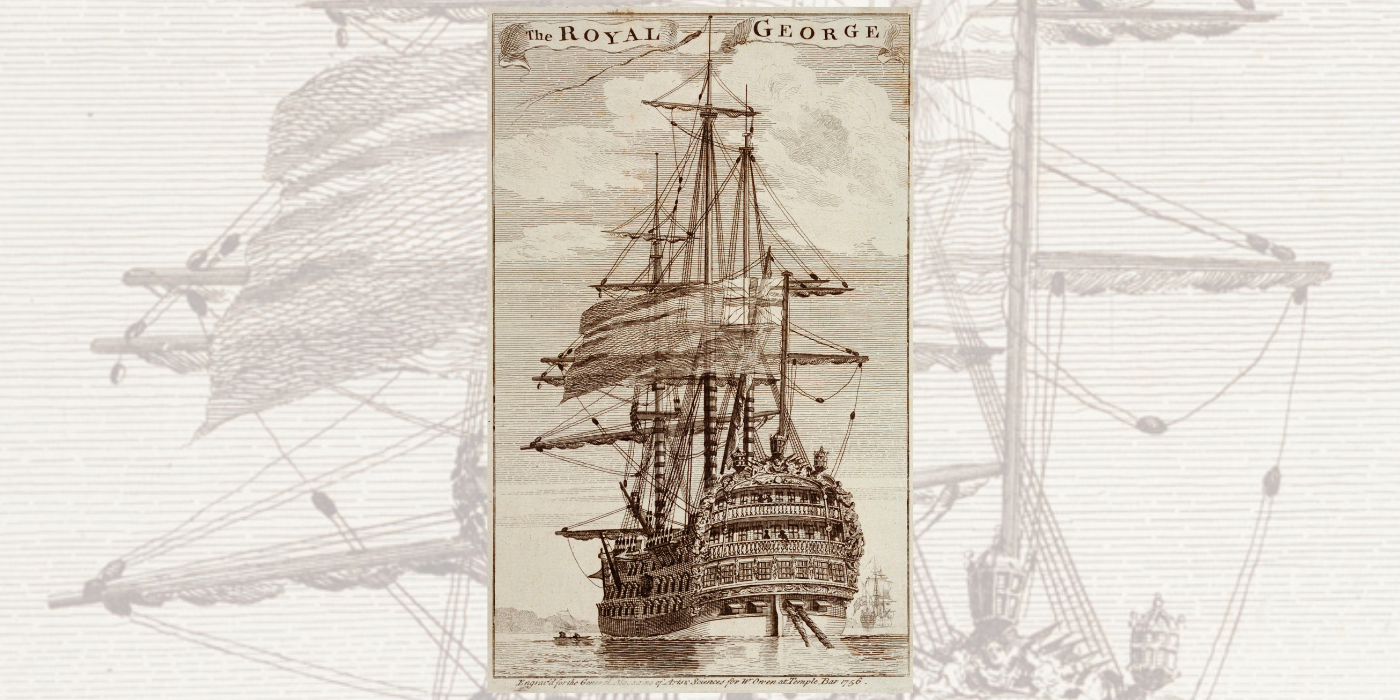

The Royal George in 1756

The Royal George was a formidable wooden warship with three decks and more than 100 guns (cannon) that had taken a decade to build at Woolwich Dockyard. Launched in 1756, she was the largest warship in the Royal Navy, but by 1782 there were two more 100-gun warships – Britannia and Victory.

The Royal George was named after King George II. Because his eldest son Frederick died in 1751, it was Frederick’s son George who became George III on the death of his grandfather George II in 1760.2 Some years later, scale models of several warships were commissioned to stimulate George III’s interest in the Royal Navy. The Royal George model is in the National Maritime Museum at Greenwich, and under Lloyd’s Register Foundation Heritage and Education Centre’s programme of ‘Maritime Innovation in Miniature’.

A 5-minute video of this exquisite 1:48 scale model can be viewed here.

When France sided with the American colonies, the possibility arose of destroying Britain’s sea power, but Spanish naval support was crucial. By promising to help gain control of Gibraltar and Minorca, the French persuaded Spain to act with them against Britain. This led to the tiny territory of Gibraltar being besieged and blockaded by land and sea from June 1779 to February 1783 by Spanish and, later on, French forces. Minorca was also besieged, and an attempt was made to invade Britain.

A key role of the Royal Navy was to protect convoys of British merchant vessels. In December 1779, the Royal George – flagship of Rear-Admiral Sir John Lockhart Ross – was one of several warships that sailed from Portsmouth and Plymouth on the 1,500-mile journey to Gibraltar, escorting a substantial relief convoy of merchant ships, victuallers, and transports. They arrived three weeks later with much-needed provisions, ammunition (especially gunpowder and cannonballs) and troops. The garrison and officers enjoyed sociable gatherings, and some were hosted by Mrs Miriam Green, wife of Gibraltar’s chief military engineer. She noted in her diary: ‘Sir J. Ross has pressed me exceedingly, to go on board the Royal George and to take a rough dinner with him on Wednesday ... I should very well like to see so fine a ship, particularly as Sir John is so pleasing and so cheerful a man.’ Alas, the fleet sailed before that visit took place.3

In March 1781. another relief convoy left Portsmouth, accompanied by various warships, notably the Royal George and Britannia. On 12 April, one soldier watched it arrive in the Bay of Gibraltar as the fog lifted, revealing ‘one of the most beautiful and pleasing scenes it is possible to conceive. The Convoy, consisting of near a hundred vessels, were in a compact body, led by several men of war.’ After besieging Gibraltar for almost two years, the Spanish forces chose this moment to begin a devastating bombardment. The provisions were hurriedly unloaded, and the warships and other vessels sailed away.4

Gibraltar

Gibraltar’s North Front

Approximate position of the Royal George at Spithead

The following year, 1782, the French and Spaniards decided to attack Gibraltar with floating batteries converted from old merchant ships, supported by warships and thousands of troops on land. When intelligence of this reached Britain, a huge convoy was planned, protected by the entire Channel Fleet, but fears grew that it would be too late.5 Towards the end of August, the Grand Fleet, as it was known, was assembled at Spithead, and last-minute tasks were being done. The Royal George was now the flagship of Rear-Admiral Richard Kempenfelt, with Martin Waghorn as Captain. The crew consisted of about 850 men and boys, including marines. In spite of the urgent situation, respectable sightseers were welcome on board, and the Reverend Richard Cumberland and his cousin paid a visit:

We took a wherry and went aboard the Royal George at Spithead – as being one of the finest ships in the fleet. We met with the most civil behaviour from the officers, who shewed us every part worth seeing ... We took notice of the number of women on board and they assured us there were above 400 and near double the number of men. 6

Every warship would have been crowded with traders and prostitutes, ‘Portsmouth Polls’, who were ferried in small boats from the mainland.7 Midshipman Francis Vernon, who went to Gibraltar with the 1780 convoy, described his own ship, the Terrible, at Spithead: ‘Our ship’s company could now revel in the delights of Portsmouth, and filled the ship with hundreds of these obliging females, who desert the capital during the war, and reside in the genteel recesses of Portsmouth, and other naval towns.’8 This was now the scene on board the Royal George – hundreds of prostitutes, along with traders and some wives and children saying their farewells. Several seamen and officers had gone ashore, but workmen from Portsmouth Dockyard had also arrived to do a repair.

For tasks like washing the decks of large wooden warships, seawater was hauled up in buckets or else it was pumped from a cistern positioned below the waterline. A cistern’s seawater came from one or two pipes that went right through the hull, with a brass cock or tap to turn off the flow.9 Sources are conflicting, but the Royal George probably had only a starboard pipe, which no longer worked: ‘in all ships there is a leaden pipe with a cock to it, under water, to clean and sweeten the ship, and this pipe being broke, another was ordered to be put in’. According to the seaman James Ingram, ‘The water-cock is something like the tap of a barrel, –– it is in the hold of the ship on the starboard side, and at that part of the ship called the well. By turning a thing which is inside the ship, the sea-water is let into a cistern in the hold, and it is from that pumped up to wash the decks.’10

The repair could have been postponed or else carried out in Portsmouth Dockyard, but it was decided to tilt (‘heel’) the Royal George by running out the guns through the port (larboard) gunports to shift the weight, while the ropes holding the starboard guns were eased, enabling them to be rolled back towards the centre of the ship. This should have been enough to expose the outlet of the starboard pipe, but it remained submerged, and so the cannonballs (‘shot’) were shifted to the port side to tilt the vessel further.

While the repair was taking place, the 50-ton Lark sloop victualler was lashed to the port side of the Royal George, and casks of rum were hauled up in a sling. James Ingram helped to unload them on the upper deck, adding more weight to the port side. The lower deck gunports were sinking closer to the level of the sea, and the waves caused water to pour over the sills. The ship’s carpenter became uneasy, but his pleas to right the ship were rebuffed.

Suddenly, the alarm was given that the Royal George was sinking, followed by the order to right the ship. As the seamen rushed towards the guns to haul them back in, the rapid movement of so many people to the port side caused the vessel to literally fall over sideways, on top of the Lark. The Royal George then disappeared incredibly fast, trapping hundreds of people who were drawn down almost to the seabed by the vortex of the sinking vessel. Once she was filled with water, the huge warship came to rest in a more upright position, with the masts visible above the water.

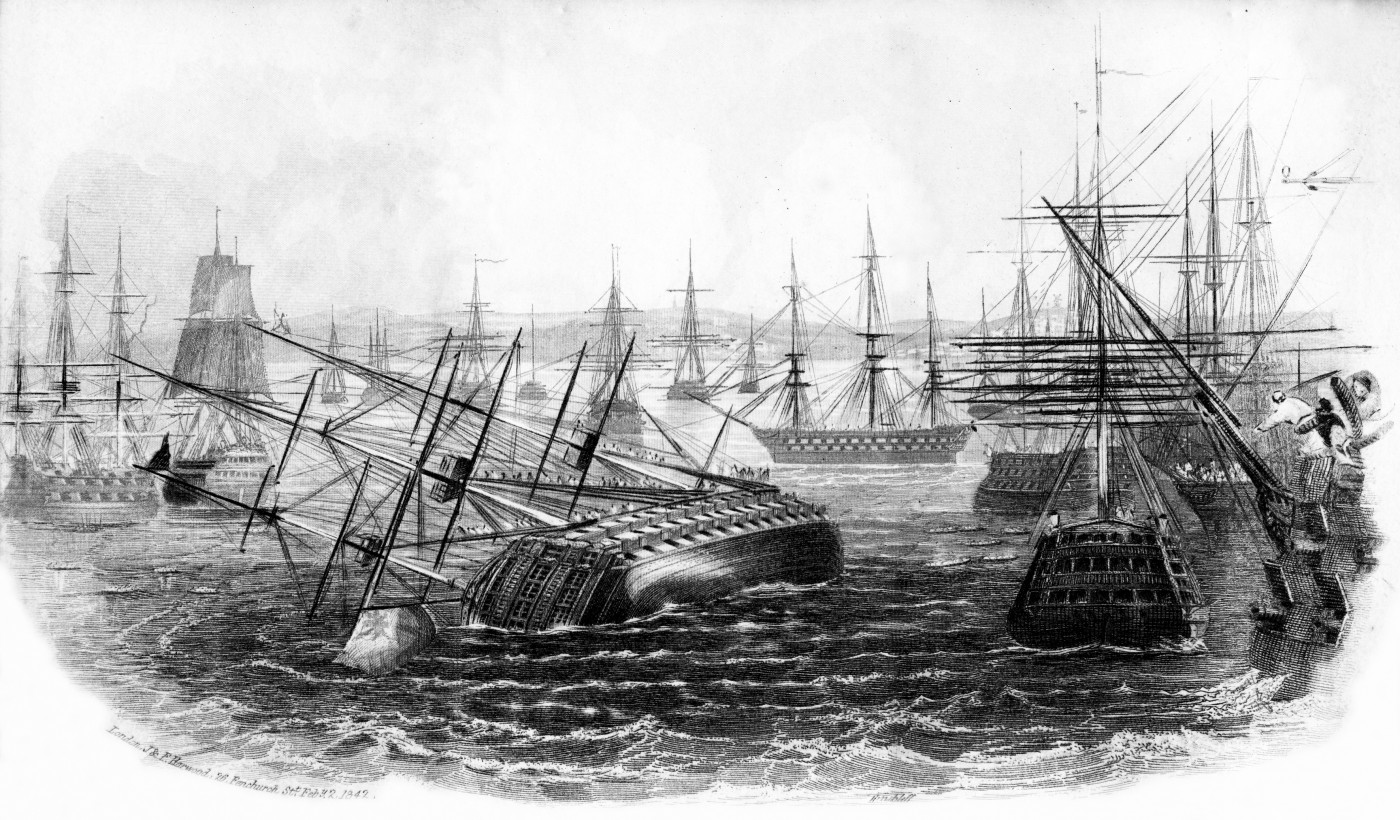

Artist impression of the crowded anchorage at Spithead

a miniature book bound in wood from the wreck

The Royal George memorial at Ryde

A Dutch medal, 1783

As Richard Cumberland and his cousin walked towards Southsea, they were told that a substantial ship had foundered. All they could see were small boats clustered round a ship’s masts protruding above water. On returning to Portsmouth, they were shocked to learn that this was the Royal George. Bodies were already being brought ashore, and although the pair tried to help, most were dead.11 Few people at that time could swim, though many were saved by clinging to the rigging until rescued by boats from nearby ships or from the mainland. A few days later Samuel Kelly arrived at Spithead on board the packet ship Grenville and moored nearby:

The rigging of the Royal George was decorated, not with colours, but with dead bodies, who were hung up by arms, legs, etc., which presented a horrid spectacle. These men had floated at high water, and to prevent the tide carrying them away, had been tied fast to the shrouds and mainstay, and at low water ... they were suspended several feet above the water. 12

At least 900 people (probably more) drowned in a few minutes, including many crew members, marines, dockyard workers, merchants, wives, children, and hundreds of prostitutes. Countless bodies were swept away by the tides, and many were washed up at Ryde on the Isle of Wight and at Portsmouth. Very often they were stripped of their clothing and possessions, making them impossible to identify, before being buried in mass graves. Newspapers across the country carried reports of the shocking event, including the death of Rear-Admiral Kempenfelt, whose body was never recovered, and speculation about the cause of the tragedy was rife.13

A few survivors, including Captain Waghorn, were called as eyewitnesses at the brief court martial on 7 September.14 The official verdict was that the Royal George was not over-heeled, that everything possible was done to right the ship and that the cause of the sinking was the failure of part of the frame.15 In the court martial, rotten timbers were mentioned, as well as a jerk or crack just before sinking, but most people heard nothing, and warnings that the vessel was tilted too much had been given at least 20 minutes before the ship sank. Over the years, blame has also been put on corrosion caused by copper sheathing and a sudden squall, but all have been disproved.16

William Nichelson, an old acquaintance of Kempenfelt, was Portsmouth Dockyard’s Master Attendant, and over a decade later he published a detailed analysis of what went wrong. He had advised Kempenfelt the day before not to do this repair. The ship was not leaking, he said, and so it was unnecessary and dangerous, especially being fully laden. He believed he had convinced Kempenfelt and so was horrified at what happened. In his view, the lower-deck scuppers (drains) should have been plugged up, the lower-deck guns should not have been run out, and the gunports should have been closed, secured, and caulked. It was unwise to have moved cannonballs, as they were impossible to shift back speedily in an emergency. Nichelson also said that the Lark should not have been unloaded on the port side. In addition, there was no clear chain of command, and the key officers – gunner, master and boatswain – were on shore. He did not comment on the wisdom of filling the ship with prostitutes, merchants, and other visitors, as that would have meant addressing the welfare and recruitment of crews.

The Grand Fleet finally set sail on 11 September. Two days later France and Spain launched what should have been a devastating attack against Gibraltar, but it was a disaster, as the defenders of the Rock set fire to the floating batteries and achieved an unexpected victory. Poor weather disrupted the passage of the convoy, so they did not arrive until 11 October. The siege finally ended in February 1783, and with the loss of the American colonies, Gibraltar became a national symbol for Britain and a crucial naval base.

Footnotes

-

1

Roy and Lesley Adkins 2017 Gibraltar: The Greatest Siege in British History (published in the UK by Little, Brown and in the US by Viking; available in hardback, paperback, e-book and audiobook).

-

2

George III is often incorrectly stated as the son of George II

-

3

Adkins 2017, pp. 117–21

-

4

Adkins 2017, pp. 185–219.

-

5

Adkins 2017, pp. 299–300.

-

6

Adkins 2017, pp. xx–xxi.

-

7

Roy and Lesley Adkins 2006 The War for All the Oceans (London: Little, Brown), pp. 174–81; Roy and Lesley Adkins 2008 Jack Tar: Life in Nelson’s Navy (London: Little, Brown), pp. 153–68.

-

8

F. V. Vernon 1792 Voyages and Travels of a Sea Officer (London), pp. 9–10.

-

9

Peter Goodwin 1987 The Construction and Fitting of the Sailing Man of War 1650–1850 (London: Conway), pp. 138–44.

-

10

Benjamin Thorn 1845 An Account of the “Royal George,” sunk at Spithead, August 29, 1782, with the particulars relative to her sinking (London), p. 3; ‘The loss of the Royal George’ Penny Magazine 3 1834, pp. 174–6.

-

11

Adkins 2017, pp. xxii–xxiv.

-

12

Crosbie Garstin (ed.) 1925 Samuel Kelly: An Eighteenth Century Seaman (London, Jonathan Cape), p. 62.

-

13

Many newspaper references, as well as a lengthy biography of Kempenfelt, are included in Hilary L. Rubinstein 2020 Catastrophe at Spithead: The sinking of the Royal George (Barnsley: Seaforth).

-

14

Rubinstein 2020, pp. 121–46.

-

15

See ‘The loss of the Royal George’, pp.149–55 in H.W. Hodges and E.A. Hughes (eds.) 1922 Select Naval Documents (Cambridge: University Press).

-

16

Rubinsten 2020, pp. 147–73; R. F. Johnson 1971 The Royal George (London: Charles Knight), especially pp. 179–86.