In the one-room Scarborough Maritime Heritage Museum on England’s east coast, a dark-blue sweater hangs on display. It is a gansey, elsewhere known as the guernsey or ganzie, and it was once as essential to a fisher’s safety as the PFD (Personal Flotation Device) or oilskins.

A gansey was a very tightly knit sweater knit to no written pattern: patterns were handed down through families, and the usual tale is that each village had its own so that drowned fishers could be recognised by their jumpers. A local knitter in Whitby who runs a festival called Propagansey is scornful of this theory, but certainly there were different patterns, sometimes with the addition of a deliberate mistake so that each family member had his unique gansey.

Staithes knitters knit horizontal bands to signify birds’ eyes, “separated by narrower bands of knit 2 rows, purl 2 rows” to signify the ploughed fields up on the cliff tops. Whitby had triangles to denote ship’s flags and horizontal thick lines to convey Whitby’s 199 steps up to the abbey. In Filey, they used a double moss stitch to illustrate the pebbled beach, and a zigzag that some theorise conveyed the “ups and downs of married life”.

Ganseys were hard to knit, requiring the use of 5 needles at once, and having no seams. The closeness of the knit was to ensure warmth and waterproofing: ganseys were worn against the skin, with perhaps cloth at the neck and wrists to prevent chafing. A couple of years ago, I found that the gansey was listed as “endangered” on the Heritage Crafts site. It is classed as “intangible cultural heritage” because of how patterns were handed down. But this year the listing was removed, because there are decisions to be made about “whether we set the definition as those makers who have been passed the skills in a one-to-one transmission of tacit knowledge originating in the traditional fishing communities within which the craft originated, or whether we include the thousands of general knitters who have learnt gansey styles from the many published patterns and sources,” according to its executive director.

Jack Cross and his son Ned Cross of Flamborough, Flamborough Manor in Ganseys

Emptying a fishing net aboard the Merlin

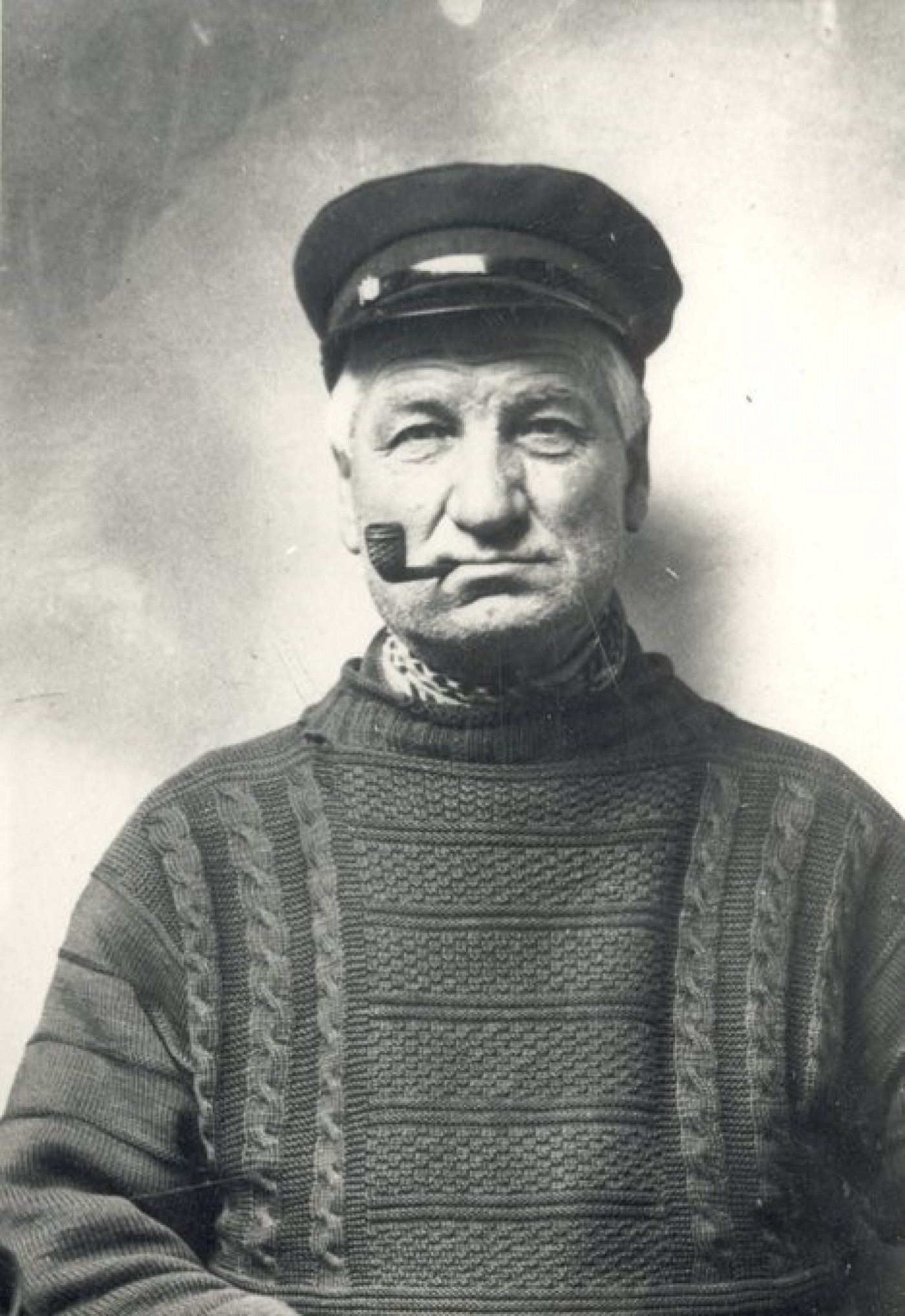

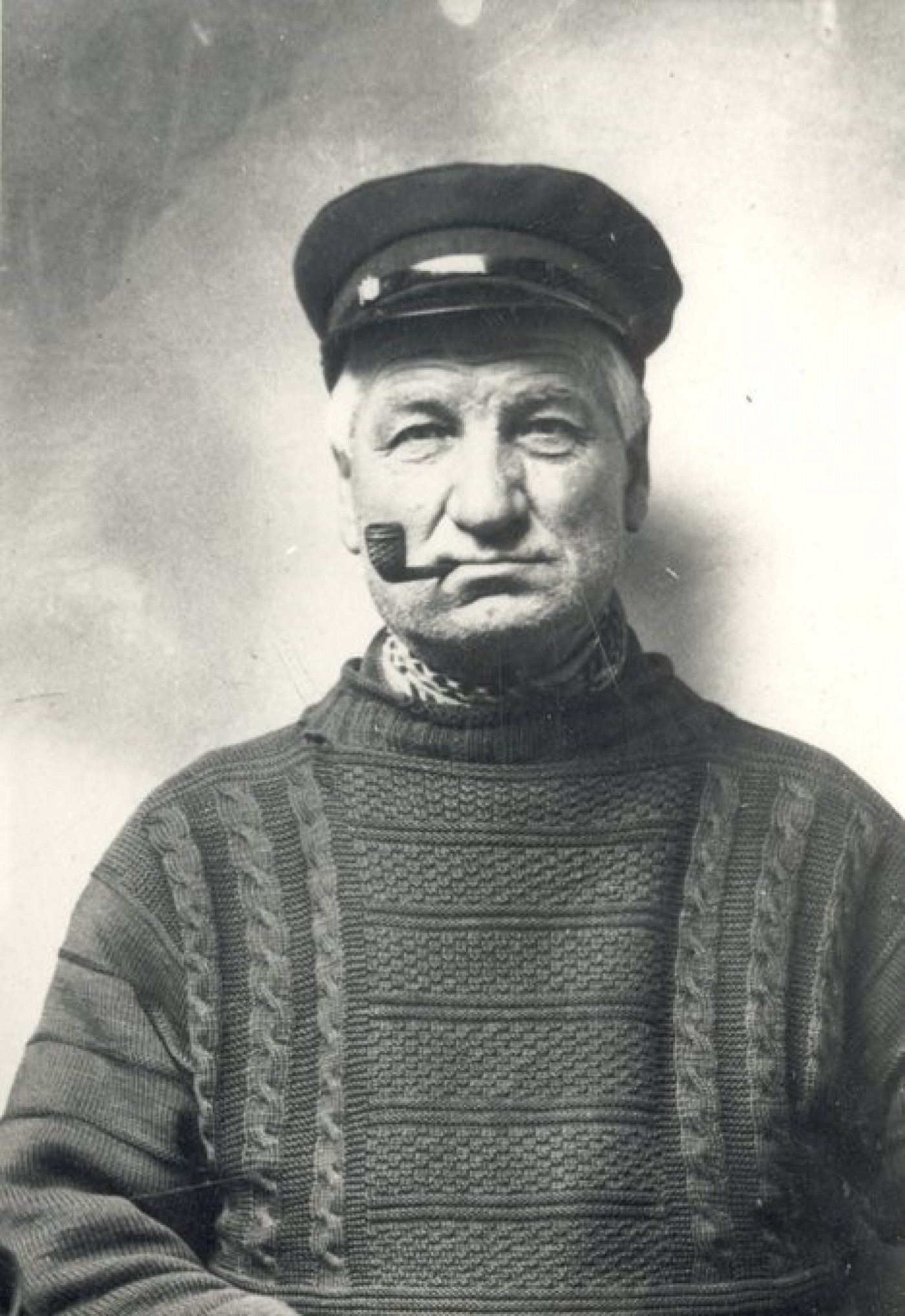

Duggie Carter wearing a Gansey

Jack Cross and his son Ned Cross of Flamborough, Flamborough Manor in Ganseys

Emptying a fishing net aboard the Merlin

Duggie Carter wearing a Gansey

I cannot imagine the same discussion being held over a personal flotation device or a pair of Guy Cotten oilskins: but each is equally essential to fishing culture. Protecting the body from the elements comes in all sorts of guises. Oilskins used to be sailcloth soaked with oil or paint. On the website of the Nova Scotia Museum, a staffer has a page called “My favourite things,” which features oilskins that, she says, date back to the 1700s. I doubt that: understanding that being at sea meant protecting yourself as best as possible must be as old as the oldest seagoing vessel. The modern oilskin is attributed to New Zealander Edward Le Roy, who used linseed and wax. Helly Hansen, the Norwegian captain who launched sou’westers (long since historical, sadly) and oilskins in the late 19th century, sold 10,000 in the first five years. Guy Cotten (slogan: “l’abri du marin”, or “the protection of sailors”), began in 1964 and now has 4,500m2 of factory space. Its innovation was to use PVC, to replace the heavy and cumbersome waxed cloth.

Rex Harrison in Guy Cotten, Filey

Rex Harrison on Filey Beach in Guy Cotten Oilskins

Rex Harrison in Guy Cotten, Filey

Rex Harrison on Filey Beach in Guy Cotten Oilskins

You’ll get no argument from fishers about wearing oilskins. PFDs though, I’ve seen fishers in the UK not wearing a PFD at sea or putting one on only when they come in sight of the harbour master. Increasingly that is the minority. Elsewhere in the world things are different. In Senegal, at Mbour’s fishing village beach, I watched one day at midday as the fishing pirogues landed. Pirogues are huge wooden canoes that feature colourful painted sides, wooden benches, and no shelter. Some carry 50 men and spend a week at sea, keenly hunting for diminishing stocks of sardinella, a pelagic fish that is the Senegalese’s staple food, which are now targeted by industrial trawlers and turned into fishmeal for European and foreign markets. I watched as a pirogue beached, and two dozen men tugged the nets onto the shore, and it looked like a balletic pass the parcel. None were wearing lifejackets, but I spotted at least one pair of Guy Cotten oilskins. My guide told me that the lifejackets would be still in the boat, because they are precious.

Fisherman's Village, Mbour

Fishing Pirogues at Rest at the Fisherman's Village, Mbour

Fisherman's Village, Mbour

Fishing Pirogues at Rest at the Fisherman's Village, Mbour

I wonder: In Senegal, figures for how many fishers are lost at sea are hazy, but it is definitely a lot. “They won’t wear them,” says Gaussou Guèye, secretary general of CAOPA (Confédération Africaine des Organisations de Pêche Artisanale), an association that represents artisanal fishers throughout West Africa. “They say that lifejackets are for people who are scared, or people who aren’t fishermen or people who can’t swim.” I cannot go to sea with them to see for myself: Guèye also says that fishermen will not take a woman to sea, because she is menstruating, or menopausal or just because she is a woman.

A fisher who had just disembarked came up to me and asked if I am married and whether I wanted to go fishing. Don’t trust him, said my guide. Look at his red eyes. They are all drugged or drunk. They have to be, to survive all that time in dangerous waters in an open boat. The drug and drink are another form of protection, though not one recommended by maritime authorities. Now that stocks are threatened, the pirogues have to go further out to find fish. There is more danger now. Again, the records are hazy, but everyone in Mbour knows someone who has left on a pirogue to reach the Canary Islands then Europe. And everyone knows someone who has drowned. It used to be so common, there was a slogan. “Barca ou barzakh.” Barcelona or death. A PFD, a pair of oilskins, a sou’wester, a gansey: none of that will change their reality. For these pirogue fishers, the sea will always bring life, in the sardinella that used to be bountiful, and it will always bring death, from their desperate efforts to snatch disappearing stocks or to escape.