Vast amounts of ballast were needed to keep ships safe, which had a severe impact on the environment, especially in its disposal. Some ballast was reused as building materials, but much was dumped illicitly or at controlled shores. In places like the River Tyne, unsightly ballast hills were formed, changing the landscape. Archaeological objects inadvertently carried with ballast have confused evidence relating to the past, while plants, seeds and various creatures have been introduced far from their origins, causing ecological harm. Unsuitable ballast materials, like manure and refuse, could pose a hazard for seamen, and ballast was even subject to quarantine regulations because of contagious diseases.

Why ballast was needed, how it was obtained, the materials involved, how it was loaded and secured, ships sailing ‘in ballast’, how ballast was discharged and regulations concerning ballast are issues that we discuss in the story Ballast: A Hidden History on How to Avoid Shipwreck. In the next story, Crank and Stiff Ships: The Impact of Ballast on Maritime Disasters, we talk about shipwrecks and other problems caused by a failure of ballasting. The story of ballast in relation to safety at sea is complex and multi-faceted. The type of ballast available for ships across the globe varied immensely and included sand, gravel and mud dredged from rivers, sand and shingle from shorelines, industrial and domestic waste, building debris, and quarried sand, stone and chalk. Especially from the 18th century, staggering amounts of ballast were supplied, all for temporary use, which were subsequently dumped or recycled, significantly affecting landscapes and ecosystems. 1

Wherever ships went, there was ballast. At the destination port it might be dumped in the sea or discharged on land, while some might be loaded aboard other vessels needing ballast, involving further journeys. When Eric Newby joined the crew of the steel four-masted barque Moshulu at Belfast in 1938, he recorded that they took on ballast of sand, pieces of paving stone, granite blocks, and rubble from a house, all of which was thrown overboard at Port Victoria, Australia, so that they could load a cargo of grain. 2

Clues of ballast disposal can be seen in alien geological material, perhaps on the shore or reused at the destination port in buildings and other structures. One example is the 1855 Congregational Church in Charles Street, Cardiff, later known as the Ebenezer Chapel and also as the ‘ballast chapel’, because it was supposedly built using ballast stone from all over the world. 3 In the 19th century merchant ships from Malta often arrived at Gibraltar with limestone as ballast, which was discarded before returning with all manner of goods. The reuse of this attractive yellow stone, by Maltese craftsmen, greatly influenced Gibraltar’s architectural styles, though at the Sacred Heart Church (built from 1874) the limestone proved too soft for the damp climate, necessitating much restoration. 4

Castle Road, with the Sacred Heart Church, Gibraltar

Entrance to the Sacred Heart Church, Gibraltar

In numerous places on the Atlantic coast of Canada and the United States, geologists have identified flint pebbles and nodules from the Upper Cretaceous chalks of Europe, dumped in shingle ballast by ships from France and England. Construction projects exploited unusual and attractive stones worldwide, including large pebbles laid as cobblestones in streets. Charleston in South Carolina is well known for its cobbled streets, which date from about 1800 and used ballast pebbles that were discharged before ships took on cargoes of tobacco and cotton. 5

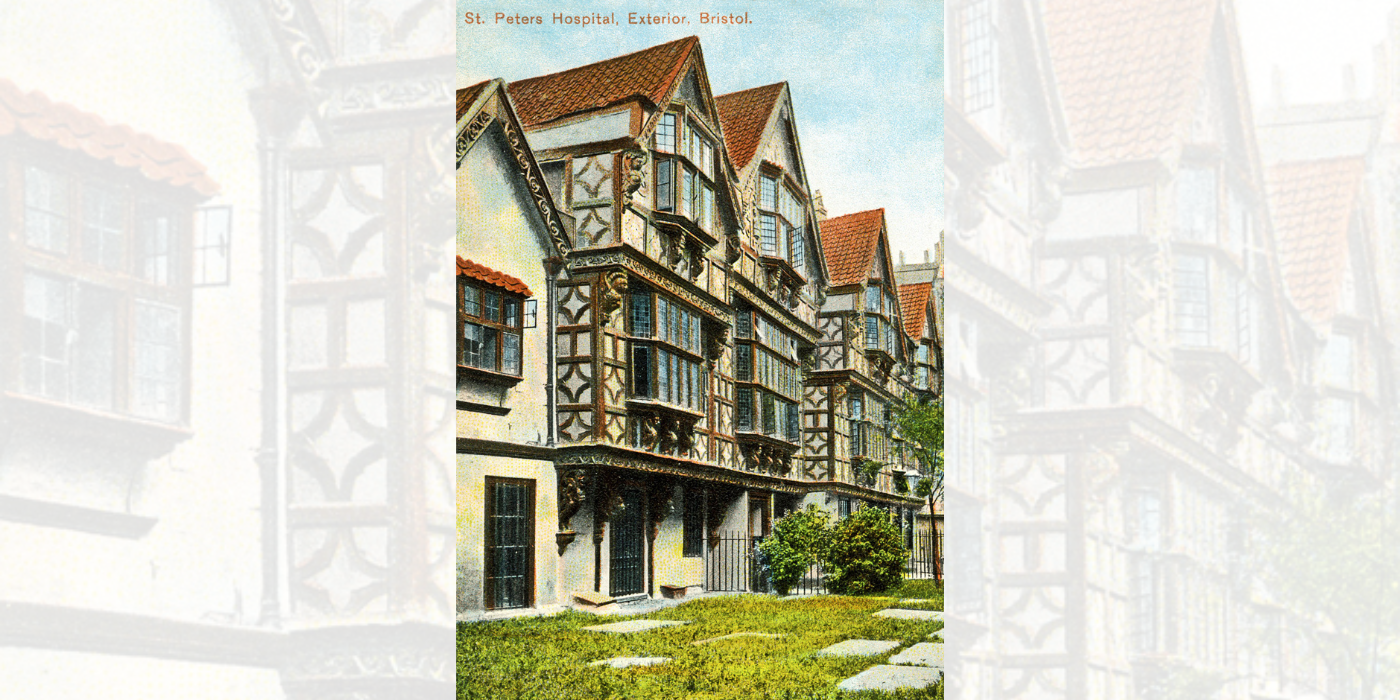

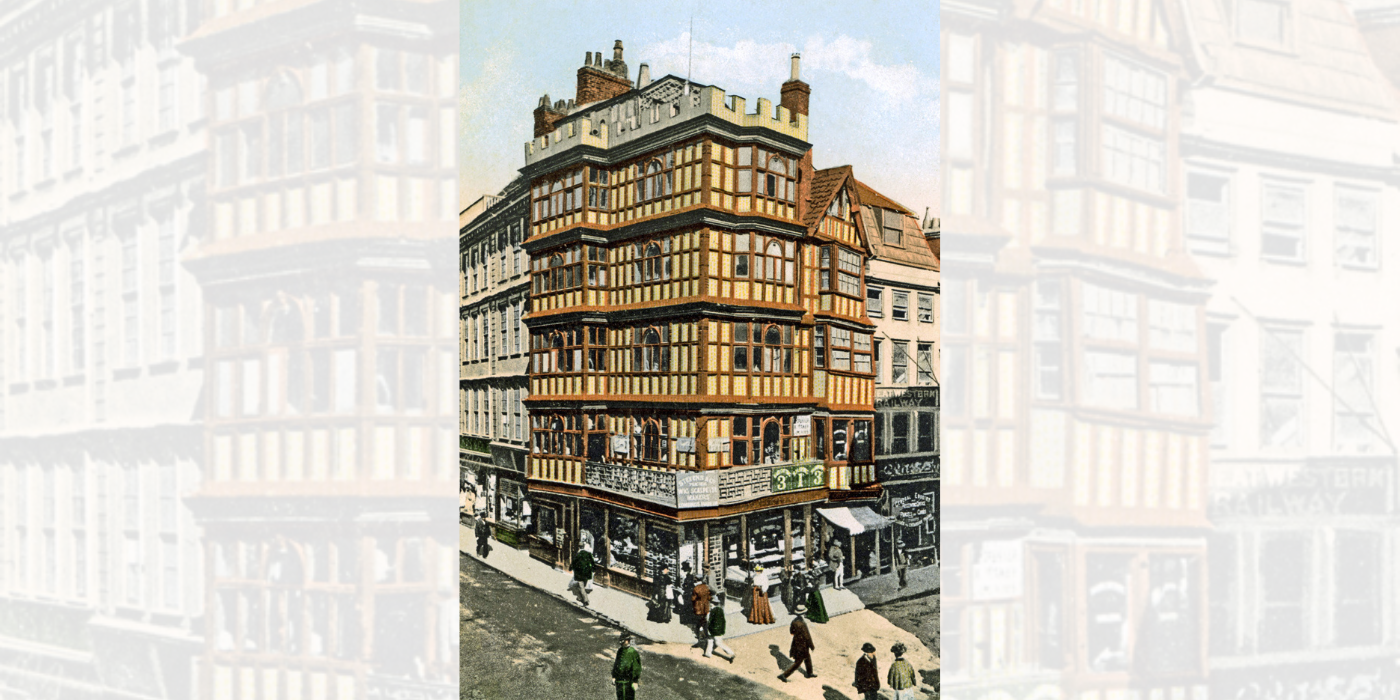

Rubble was preferred for ballast, usually quarried stone or debris from demolished structures. Early on in the Second World War, the United States of America provided large shipments of supplies to Britain, many of which docked at Bristol, a historic city that suffered terrible air raids. With no return cargoes, the supply ships were loaded with debris from the bombed buildings to serve as ballast. Back in New York, it was dumped in the East River as part of a landfill programme, and in 1942 a plaque was set up by the English-Speaking Union of the United States to mark Bristol’s contribution. 6

Cobblestone street in Charleston, South Carolina

Medieval St Peter’s Hospital, Bristol

Dutch House, Bristol

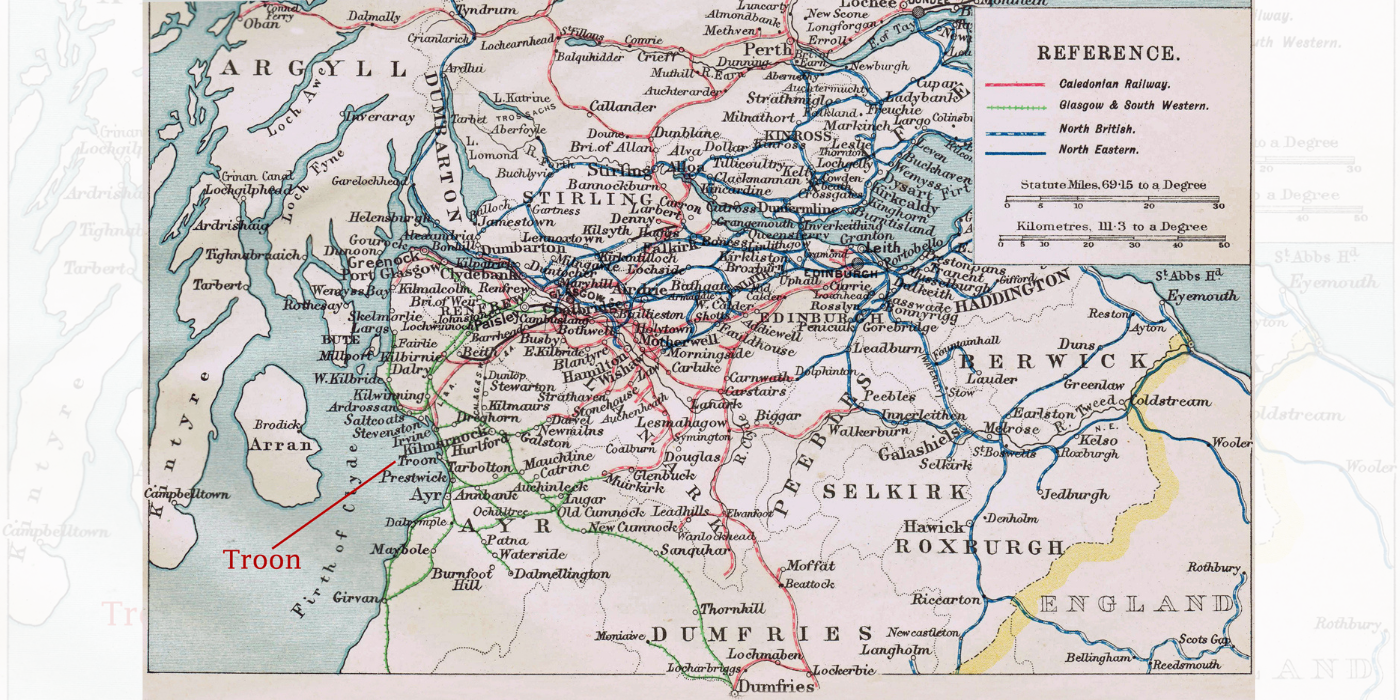

As described in ‘Ballast: A Hidden History on How to Avoid Shipwreck’, ballast that was offloaded along river banks or on quays could be diverted to ships requiring ballast, sold to industries such as construction and glassmaking, or shifted inland. Ballast banks and ballast hills developed on coasts far and wide, and some islands were formed offshore. At the town of Troon in Ayrshire, Scotland, an immense bank was constructed from 1840 by the Duke of Portland to protect the new harbour from westerly gales, which enabled Troon to develop into an important port. Made from material excavated from the harbour and from ships’ ballast, the ‘Ballast Bank’ ran along the seaward side of the peninsula at Troon, where houses were once prone to flooding, as the Presbyterian Minister John Kirkwood wrote in 1876:

Such inundations have not been heard of since, and we have reason to hope never will. The raising of the bank, in front of Portland Terrace, by ballast from the ships, has effectually shut out the wild Atlantic tide. By the same means the fine green sward extending from the Terrace to the offices at the Harbour, and the entire mass of the wedge-shaped height known as the Ballast Bank, have been formed ... not very shapely in itself nor poetic in its designation, but which, with a little labour, might be made as attractive as the famous Hoe at Plymouth. 7

The Ballast Bank became a landmark and was celebrated by the Scottish poet John Laing in ‘To Troon’, written in 1888:

Ye ha’e your famous Ballast Bank,

Whaur gorgeous sichts are seen;

Wi’ greater heights ’twill even rank,

It honoured Prince and Queen.

When to its top we only reach,

We scarcely wad come doon,

For at oor feet full is the beach,

An’ miles o’ scenery roon. 8

The Ballast Bank at Troon, Scotland

Location of Troon, Scotland

The largest ballast hills were east of Newcastle along the River Tyne, and for over four centuries ships departed, laden with coal from the nearby mines. Most came back in ballast, generally taken from the River Thames, and much of it was discharged at the ballast shores or wharves of the Tyne and then removed a short distance to the artificial ballast hills.

In 1797 an advertisement was placed in the Newcastle Courant: ‘To be LET ... THE CONVEYING of the BALLAST, landed on Willington Quay, on the North Shore of the River Tyne, to the Ground lately purchased by the Corporation behind the said Quay. Persons desirous of contracting with the Corporation of Newcastle, for conveying this Ballast for a Term of Years, are requested to send Proposals, in writing.’ 9 A fixed steam engine at the top of the growing ballast hill drew the trains of laden waggons up the incline from the quay, and in 1802, at the age of 21, George Stephenson (who later built the ‘Rocket’ locomotive) took on the job of brakesman, as his biographer recorded:

Willington Quay, whither Stephenson now went to act as brakesman at the Ballast Hill, lies on the north bank of the Tyne, about six miles below Newcastle. It consists of a line of houses straggling along the river side; and high behind it towers up the huge mound of ballast emptied out of the ships which resort to the Quay for their cargoes of coal for the London market. The ballast is thrown out of the ship’s hold, into waggons laid alongside. When filled, a train of these is dragged up the steep incline which leads to the summit of the Ballast Hill, where the waggons are run out and their contents emptied to swell the monstrous accumulation of earth, chalk, and Thames mud, already laid there, probably to form a puzzle for future antiquaries and geologists, when the origin of these immense hills along the Tyne has long been forgotten. 10

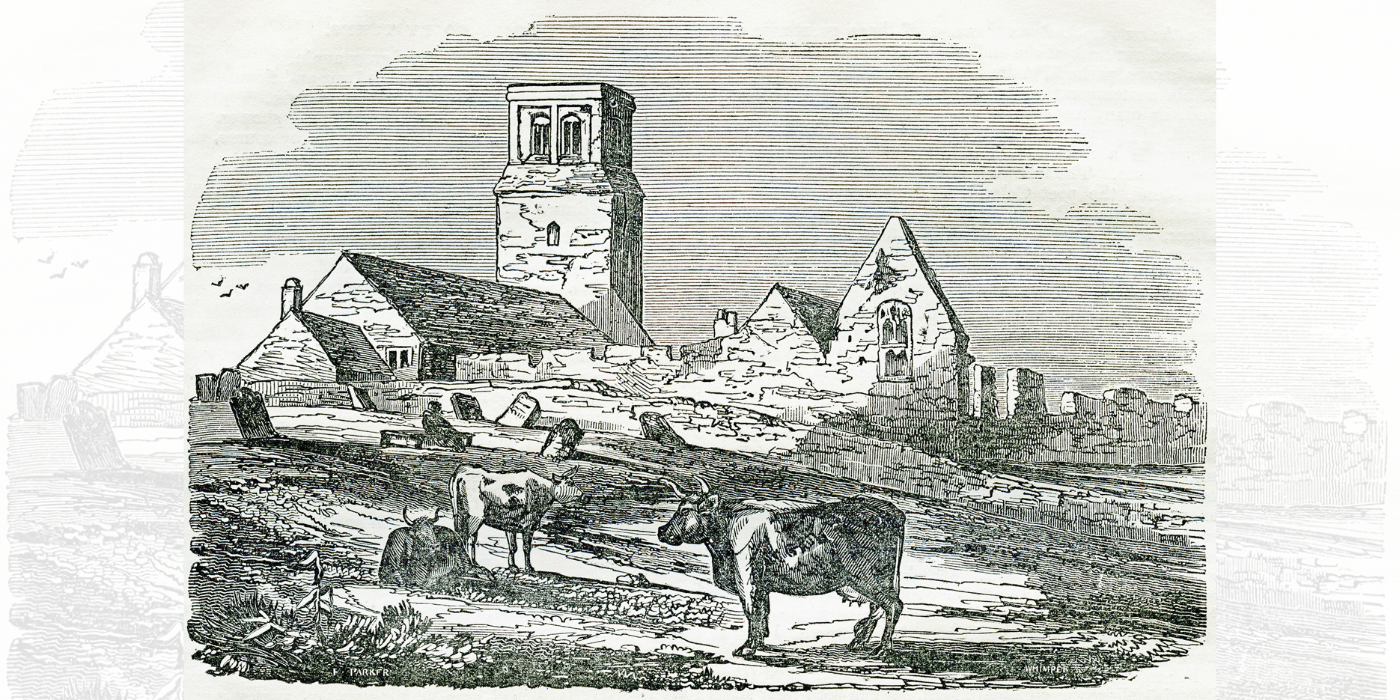

The traveller Walter White looked at other encroaching ballast hills from the top of Jarrow’s church tower, on the opposite side of the river, in July 1858:

... you see portions of the village, a good house or two, a few trees, smoke and chimneys to spare, and hills and hummocks created out of ballast. The largest advances upon a green hollow, which, in a few years, will be filled up, and buried beneath the mountain of gravel. The trains are now running upon it, bringing the ballast a mile or more from the ships in the river. When the allotted space shall be filled up, the contractors will have to cover the whole of the now bare and brown surface with green turf, so as to produce herbage. 11

Jarrow Church in 1833

Former ballast hills at South Shields

White likewise speculated about how future generations might interpret the ballast hills: ‘Will those ballast-heaps puzzle future geologists? Will the science of a thousand years hence be able to account for the presence of gravel and stones from Sweden, from France, from Spain, from the western shores of England, from beyond the Atlantic, all mingled and deposited in one heap on the banks of the Tyne?’ 12 In 1889 Aaron Watson, a Newcastle journalist, described the prodigious impact of ballast:

The whole aspect of the land round about has been changed by the deposit of ballast from ships. At many points of the Tyne there are artificial hills and embankments ... composed entirely of sand and shingle which was brought over-sea as ships’ ballast ... South Shields was a spot greatly favoured for the discharging of this refuse, and it therefore happens that what was low and, for the most part, level ground, is now absurdly uneven, some of the streets being built upon ballast, whilst others are far overtopped by mountains of sand and shingle that it would cost large sums of money to remove. 13

In November 1910 the newspapers reported that a 70-acre area of the ballast hills at Walker (between Newcastle and Willington Quay) was actually being cleared for a naval shipyard for Messrs Armstrong, Whitworth & Co: ‘No more unpromising looking site could be imagined. Great hills of ballast stand a hundred feet up from the quay level, and these all have to be levelled before the work of laying out the shipyard can be commenced ... The ballast hills are so solidly knit together that it has been found necessary to blast them, and a number of steam navvies are being rigged up.’ 14

Cultural objects have been unintentionally moved across the globe in ballast, confusing and contaminating the archaeological record. Some artefacts can be recognised as alien and totally out-of-place, but movement by ballast always needs to be considered. Ancient artefacts were inadvertently mixed with ballast, and Ryan Wilkinson has investigated coins from ballast movement, including a Roman sestertius discovered in the 1930s on the shore of Puget Sound, Seattle. Ballast Island was created at Seattle by the dumping of ballast and is now marked by a plaque: ‘In this area, once part of the bay, vessels from ports all over the world dumped their ballast. Untold thousands of tons were unloaded into the water by ship’s crews including 40,000 tons from San Francisco’s Telegraph Hill.’ 15

Potsherds and clay pipe fragments

Prehistoric axes

The River Thames has yielded thousands of objects from prehistoric times onwards, but many more were inadvertently removed with ballast, perhaps ending up on ballast hills, as occurred in early May 1778:

The John and Mary, Capt. Cummins, in the Coal Trade, from this Port to London, in casting her ballast on Mr. Cookson’s Quay at South Shields, a discovery was accidentally made of some silver coin being in it, when a number of people were set to work with riddles, and several pieces of silver and gold coins were found; the former were the shillings and sixpence of the reign of Queen Elizabeth, and the latter, value about 17s. each, of the Henries, and very fresh. The ballast was taken up in the River Thames. 16

From 1972 a considerable spread of archaeological finds was discovered off the coast of Florida, almost certainly dumped in ballast from one or more ships. The clay pipe fragments, potsherds and pottery kiln and glassmaking debris spanned more than four centuries, and it has been possible to trace their origin to specific areas of the Thames. A discovery of flint nodules and debris at New Rochelle in New York was also confusing, as the flints appeared to be worked prehistoric ones, but during detailed research it was concluded that they were natural, and the presence of ceramic crucible fragments marked ‘Battersea Round’ and ‘Morgan North’ showed that this too was ballast from the River Thames. 17

Potentially hazardous material might be disposed of as ballast, which was unpleasant for crews and cargoes. As a joke, stevedores at Belfast concealed two dead dogs in the ballast of the Moshulu, which Newby said were revealed when they were throwing their ballast overboard in the blistering Australian heat of January 1939. 18 A similar discovery was reported at Cardiff in mid-February 1894: ‘A gang of men unloading the ballast of the s.s. Durham at the Bute Docks ... turned up, to their horror, about 20 human skulls and a large quantity of human bones.’ It transpired that the Durham had taken on about 300 tons of ballast at Millwall Quay on the Thames, close to Millbank Prison, which was being demolished:

It is supposed that the skulls and bones discovered in the ballast ... are the remains of deceased convicts which had been buried within the prison walls. The Cardiff gang, in the course of their discharging operations, perceived a noisome odour, which gradually became more pronounced until the smell was positively sickening. The source of the odour at length revealed itself in the discovery of human skulls and bones, which were wound up in the discharging buckets from the hold. 19

Model of the four-masted barque Moshulu

The cargo hold hatchway of the Moshulu

As early as the 17th century, it was recognised that ballast such as mud, sand and gravel from rivers could be harmful to sailors’ health, particularly in warships where it remained, foul-smelling, for lengthy periods. In order to control contagious diseases such as smallpox, cholera and yellow fever, quarantine measures developed across the world. Even in the late 19th century ballast was feared as a means of transmission, because the spread of diseases was poorly understood. Around the coastline of the United States, enforcement measures controlled how dubious ballast was dealt with, often by disinfecting it with bichloride of mercury solution, which is toxic. A medical report of 1895–6 gave an example of a vessel from Havana in Cuba that falsely claimed to be carrying stone ballast:

Actual observation during the operation of discharge revealed the following items ... Broken tiles and plaster, portions of broken laths and other pieces of wood and timber, evidently from a demolished building; rags, very soiled and filthy; bones, recent and dried; straw, apparently from the bedding of animals in stables; the droppings of horses and other animals, and numerous other articles whose advanced stage of decomposition rendered identification impossible. 20

The quarantine station at Pensacola in Florida reported how crews suffered: ‘The claim or fear that garbage ballast will cause yellow fever is untenable, but I have known crews to suffer pretty generally with nausea and diarrhea when on board with it, and have often seen men sicken while discharging it.’ From the mid-19th century steam colliers began to carry water as ballast when returning from the Thames to north-east England, which was cheaper and more convenient. The water ballast system spread widely, but research in the late 20th century showed that water-ballast tanks were responsible for transporting samples of coastal ecological systems to different parts of the world, including pathogens like cholera. During a cholera epidemic in South America that began in 1991, cholera was detected in shellfish at Mobile Bay, Alabama, and also in the ballast water of several cargo ships at US ports in the Bay of Mexico. 21

Insects, plants and seeds can be transported in ballast, causing economic and environmental harm. Ballast water can even carry and keep alive invasive species over huge distances, disrupting native ecosystems by transferring coastal marine species worldwide. Many plant species have been introduced unintentionally to localities far from their original source, which has led to invasive species and the homogenisation of global flora. A glance at 19th-century publications, such as The New Botanist’s Guide to the Localities of the Rarer Plants of Britain, shows that botanists were drawn to coastal locations for sightings of rare plants, especially at the ballast banks and hills. In 1886 John Storrie, curator of Cardiff Museum, described how ballast plants were brought in, though few survived for long: ‘A large number of the vessels, employed in the coal trade from the port of Cardiff, arrive there in ballast, which is discharged and utilized to fill up the low-lying marshy ground near Penarth Ferry and the East Moors, and on the heaps so spread out the seeds of foreign and British plants brought in from abroad.’ He observed that many plants survived only a year or two, as the ground was being constantly disturbed, and most were natives of the French, Spanish and Mediterranean coasts. 22

Quagga and zebra mussels are native to eastern Europe, but gradually spread across Europe from the late 18th century, and they have had a particularly catastrophic effect on ecosystems from the 1980s, when they were detected in the Great Lakes, undoubtedly introduced through the release of ballast water. They have since spread to many waterways in North America and elsewhere. Gradual recognition of the scale of the problem of ballast water led the International Maritime Organization (IMO) to designate ballast water as one of the main environmental threats to oceans worldwide. In 2004 the International Convention for the Control of Ships’ Ballast Water and Sediments was adopted by IMO and came into force globally in 2017.

Over the centuries a great deal of ballast has been spread around coasts worldwide as a result of the wrecks of sunken and submerged ships breaking up. Britain has a huge number of shipwreck sites around its shores, many of which are the wrecks of sailing vessels that would have been carrying ballast from all over the world. Occasionally, the ballast has been noticed, including by the naturalist Philip Henry Gosse when in 1852 he visited Rapparee Cove near Ilfracombe, on the north Devon coast:

The floor of the cove is principally composed of sand, which changes, as it approaches low-water mark, to small shingle. Among the latter, the observant stranger notices a quantity of yellow gravel, scattered all along the water-line between tide-marks. This at once strikes him as a remarkable feature, seeing that nothing of the kind is found on other parts of this coast ... On inquiry, he learns that these yellow pebbles are strangers, and not natives of the place; that they are, in fact, the enduring records of a tragical event that occurred some fifty years ago. 23

This was the site of a shipwreck in 1796, when the London transport was returning from the West Indies and trying to enter Ilfracombe harbour in appalling weather, only to be wrecked in the adjacent cove. Most people, Gosse said, escaped with their lives, but the ballast was a constant reminder of what happened:

For years after the sad event, the people of the town used to find gold coins, and jewels, among the shingle at low tide. The vessels were ballasted with this yellow gravel, which though washed to and fro by the rolling surf, remains to bear witness of this shipwreck, and to identify the spot where it took place: a curious testimony, which probably will endure long after the event itself is lost to oblivion, and perhaps until the earth and all the works therein shall be burned up. 24

For more information on Ballast Water, watch the Ballast Water Explained: Origins, Environmental Dangers and Modern Solutions video below.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the Lloyd’s Register Group or Lloyd’s Register Foundation.

The Bristol plaque, commemorating the Blitz rubble taken as ballast to New York in the Second World War

HM Government of Gibraltar Ministry for Heritage - Sacred Heart Church, Gibraltar

Willington Quay, Newcastle Corporation Ballast Hill

Ballast Island, Seattle

Lloyd's Register Foundation - Research Supporting Safer, Stabler Ships

Useful Links to Ballast Water:

IMO - Ballast Water Management Convention

IMO - Ballast water management - The Control of Harmful Invasive Species

National Marine Sanctuaries - Invasive Mussels

Lloyd's Register - Ballast water management

Lloyd's Register - Understanding Ballast Water Management

Riviera - LR: BWMS Commission Testing Must Be By Approved Supplier

ISSUU - Ballast Water Management

Footnotes

-

1

For an analysis of the amounts of ballast involved, see pp 8–11 of Roland Wenzlhuemer 2021 ‘Shipping Rocks and Sand: Ballast in Global History’ Bulletin of the German Historical Institute 68, pp 3–17.

-

2

Eric Newby 1972 (first published 1956) The Last Grain Race (London: Pan), pp 57, 163.

-

3

Jill Hutt and Mary Traynor 1991 The Churches of Charles Street (Cardiff: Charles Street Arts). The church is now a Grade II Listed Building and has been converted into a conference, arts and community centre called Cornerstone.

-

4

The church used ballast stone from various locations, including Portland in Dorset, but primarily 800 tons of Maltese limestone. Michael Ellul 2010 ‘Malta Limestone Goes to Europe: Use of Malta Stone Outside Malta’ in 60th Anniversary of the Malta Historical Society (ed Joseph Grima), pp 371–406 (see especially pp 380–1, 403); Richard J M Garcia 2014 A Mighty Fortress set in the Silver Sea: Victorian & Edwardian Photographs of Gibraltar (Gibraltar: FotoGrafiks Books), p 32.

-

5

K O Emery et al 1968 ‘European Cretaceous Flints on the Coast of North America’ Science 160 (American Association for the Advancement of Science), pp 1,225–8. Some flint nodules were utilised to make tools and gunflints, and in the 1930s nodules were collected for flint-knapping courses and for experiments in making arrowheads.

-

6

During later redevelopment the plaque was removed and reinstated in 1974 at a ceremony with the Bristol-born actor Cary Grant. Sometimes called the Bristol Basin, the area is officially the Waterside Plaza. Wenzlhuemer 2021, pp 3–4; Bristol Evening Post 11 December 1974, p 4; Bristol Evening Post 27 December 1974, p 4.

-

7

J Kirkwood 1876 Troon & Dundonald with their Surroundings, Local and Historical (Kilmarnock: McKie & Drennan), pp 2–3, 6.

-

8

The Irvine Herald 25 February 1888, p 5; republished in John Laing 1894 Miscellaneous Poems, Chiefly Scottish (Irvine and Troon: Charles Murchland), pp 43–5. Laing was a native of Troon.

-

9

Newcastle Courant 11 February 1797, p 4.

-

10

Samuel Smiles 1857 The Life of George Stephenson, Railway Engineer (London: John Murray), p 27.

-

11

Walter White 1859 Northumberland and the Border (London: Chapman and Hall), p 128. White lived in London and was a library attendant at the Royal Society.

-

12

White 1859, p 129. The church was St Paul’s.

-

13

The Rivers of Great Britain: Descriptive Historical Pictorial: Rivers of the East Coast (London: Cassell & Company), pp 167–8. Aaron Watson lived 1850–1926.

-

14

The Cambrian News 11 November 1910, p 5.

-

15

Ryan H Wilkinson 2020 ‘Identifying Ancient Coins Deposited with Modern Ships’ Ballast’ American Journal of Numismatics 32, pp 169–78 (see especially pp 174–6).

-

16

Derby Mercury 22 May 1778, p 4.

-

17

William M Jones 1976 ‘The Source of Ballast at a Florida Site’ Historical Archaeology 10, pp 42–5; F Peter Rose 1968 ‘A Flint Ballast Station in New Rochelle, New York’ American Antiquity 33, pp 240–3.

-

18

Newby 1972, pp 57, 163.

-

19

South Wales Daily News 19 February 1894, p 6.

-

20

Annual Report of the Supervising Surgeon-General of the Marine-Hospital Service of the United States for the fiscal year 1896 (Washington: Government Printing Office), p 485. See also G G Harris 1969 The Trinity House of Deptford 1514–1660 (London: The Athlone Press), p 133.

-

21

Annual Report of the Supervising Surgeon-General, p 817; Susan A McCarthy and Farukh M Khambaty 1994 ‘International Dissemination of Epidemic Vibrio cholerae by Cargo Ship Ballast and Other Nonpotable Waters’ Applied and Environmental Microbiology 60, pp 2,597–601. See also Ian C Davidson and Christina Simkanin 2012 ‘The biology of Ballast Water 25 years later’ Biological Invasions 14, pp 9–13.

-

22

Ryan J Schmidt et al 2023 ‘Hidden Cargo: The impact of historical shipping trade on the recent-past and contemporary non-native flora of northeastern United States’ American Journal of Botany 110, pp 1–22; Hewett Cottrell Watson 1837 The New Botanist’s Guide to the Localities of the Rarer Plants of Britain (London: Longman, Orme, Brown, Green, and Longmans); J C Nelson 1917 ‘The introduction of foreign weeds in Ballast as illustrated by ballast-plants at Linnton, Oregon’ Torreya 17, pp 151–60; John Storrie 1886 The Flora of Cardiff, A Descriptive List of the Indigenous Plants found in the District of the Cardiff Naturalists’ Society with a List of the other British and Exotic Species, found on Cardiff Ballast Hills (The Cardiff Naturalists’ Society), p 110.

-

23

Philip Henry Gosse 1853 A Naturalist’s Rambles on the Devonshire Coast (London: John Van Voorst), pp 339–40.

-

24

Gosse 1853, p 340.