Located in shallows a short distance off Stockton Beach near the Australian city of Newcastle are two elongated dark spots that appear intermittently, their respective sizes and forms continually altered by the movement of sand across the seabed. Positioned less than 0.3 miles (0.5 km) apart, one resembles a bullet with its business end pointed towards shore. The other lies parallel to the beach and – depending on its level of coverage – exhibits the unmistakable outline of a sailing ship, with two masts extending away from the hull into the surrounding sand. It is perhaps unsurprising these dark shapes so near to each other represent the remnants of two sailing vessels that came to grief on Stockton Beach. Somewhat unexpected is that they were both built in the 1860s at two shipyards located within 12.5 miles (20 km) of one another on Scotland’s River Clyde and their losses were separated by only a handful of years. These underwater apparitions that occasionally reveal themselves, only to again disappear beneath the shifting sands, are the wrecks of Berbice and Durisdeer.

Aerial drone image of the Durisdeer shipwreck site in 2021, when it was last completely uncovered

The Berbice shipwreck site, as captured in an aerial drone image in 2021. The Stockton Surf Life Saving Club is visible in the background.

Aerial drone image of the Durisdeer shipwreck site in 2021, when it was last completely uncovered

The Berbice shipwreck site, as captured in an aerial drone image in 2021. The Stockton Surf Life Saving Club is visible in the background.

Durisdeer was the first to slide down the slipway. Built at the shipyard of Alexander Stephen & Sons Ltd in the Glasgow neighbourhood of Kelvinhaugh, it was launched on 24 March 1864 as City of Lahore. The vessel’s hull was constructed entirely of iron plating and framing and measured 61.6 m in length. It had an extreme breadth of 9.7 m, a depth of hold of 6.5 m, and a registered carrying capacity of 988 tons 1. City of Lahore’s first owner was the Glasgow-based shipping firm George Smith & Sons, and its first voyage was from Glasgow to Bombay. The ship operated primarily between Scotland and ports in India until 1880, when ownership transferred to another Glasgow-based merchant, T.C. Guthrie 2. Renamed Durisdeer in 1882, it undertook its first voyage to the Antipodes the same year and was subsequently rerigged as a barque. For the remainder of its career, the vessel operated between Glasgow and ports in New Zealand, Australia, South America, South Africa and the West Coast of the United States.

The 717-ton ship Berbice was launched at the shipyard of Archibald McMillan & Son in Dumbarton on 25 April 1868. Its hull was of composite construction – meaning it comprised timber planking over iron framing – and had an overall length, breadth, and depth of 53 m, 9.6 m and 5.6 m. Berbice’s first owner was John Kerr of Greenock, Scotland and the vessel embarked for the West Indies on its inaugural voyage 3. Subsequent voyages would take the ship as far afield as India, the Dutch East Indies (modern-day Indonesia), South Africa, the Caribbean and South America. Following John Kerr’s death in 1872, ownership of Berbice transferred to his son Robert, who operated the ship under the banner of J. Kerr & Co. for the remainder of its existence. 4.

The discovery of abundant deposits of coal in 1797 at what is now Newcastle led to the establishment of coal mines and the colony of New South Wales’s first major export economy. The need to transport coal from Newcastle to Sydney and points beyond, and bring convict labour and supplies to the mines, resulted in a significant increase in shipping entering and leaving the Coal River (now named Hunter River) from 1800 onwards. The entrance to the river was particularly treacherous for sailing vessels during the 19th century, as it was bordered to the north by a patchwork of shallow rocks and shifting sands known as the Oyster Bank. Immediately to the north of the Oyster Bank is the low, sandy coastline of Stockton Beach. This extends for 23 miles (37 km) to the entrance of Port Stephens and has been described as perhaps the most dangerous part of the Australian coast to approach in an easterly or south-easterly gale 5.

Hydrographic chart by Lt Charles Jeffreys, RN showing some of the first documented shipwrecks at the entrance to the Coal River, including the ship Dundee (1812), brig Nautilus (1816) and His Majesty’s Colonial Schooner Estramina (1816). Image: State Library of New South Wales.

The first vessel to fall foul of the Hunter River’s entrance was the sloop Norfolk, which – after being seized by convicts on the Hawkesbury River – was wrecked and abandoned in 1800 at Pirate’s Point on the far southern end of Stockton Beach 6. Its loss would be followed by that of at least one vessel per decade until 1977, when the MV Polar Star was wrecked at Stockton Beach. In the span of 177 years, nearly 300 vessels were lost within Newcastle Harbour and in the vicinity of its entrance, the majority falling victim to the Oyster Bank and adjacent Stockton Beach 7. Included among that grim tally were Durisdeer and Berbice.

Berbice was the first of the two to succumb. Bound from Melbourne to Newcastle in ballast, the ship was meant to collect a cargo of coal intended for San Diego, California, when it encountered squally weather off Cape Howe at the border between Victoria and New South Wales. The weather steadily deteriorated and increased to a full gale as Berbice approached the Hunter River entrance on the night of 4 June 1888. The vessel’s captain, Alexander Ross, signalled for a pilot but the blue lights and rockets went unobserved and unheeded by the signal station at Nobbys Head, likely due to the inclement weather 8.

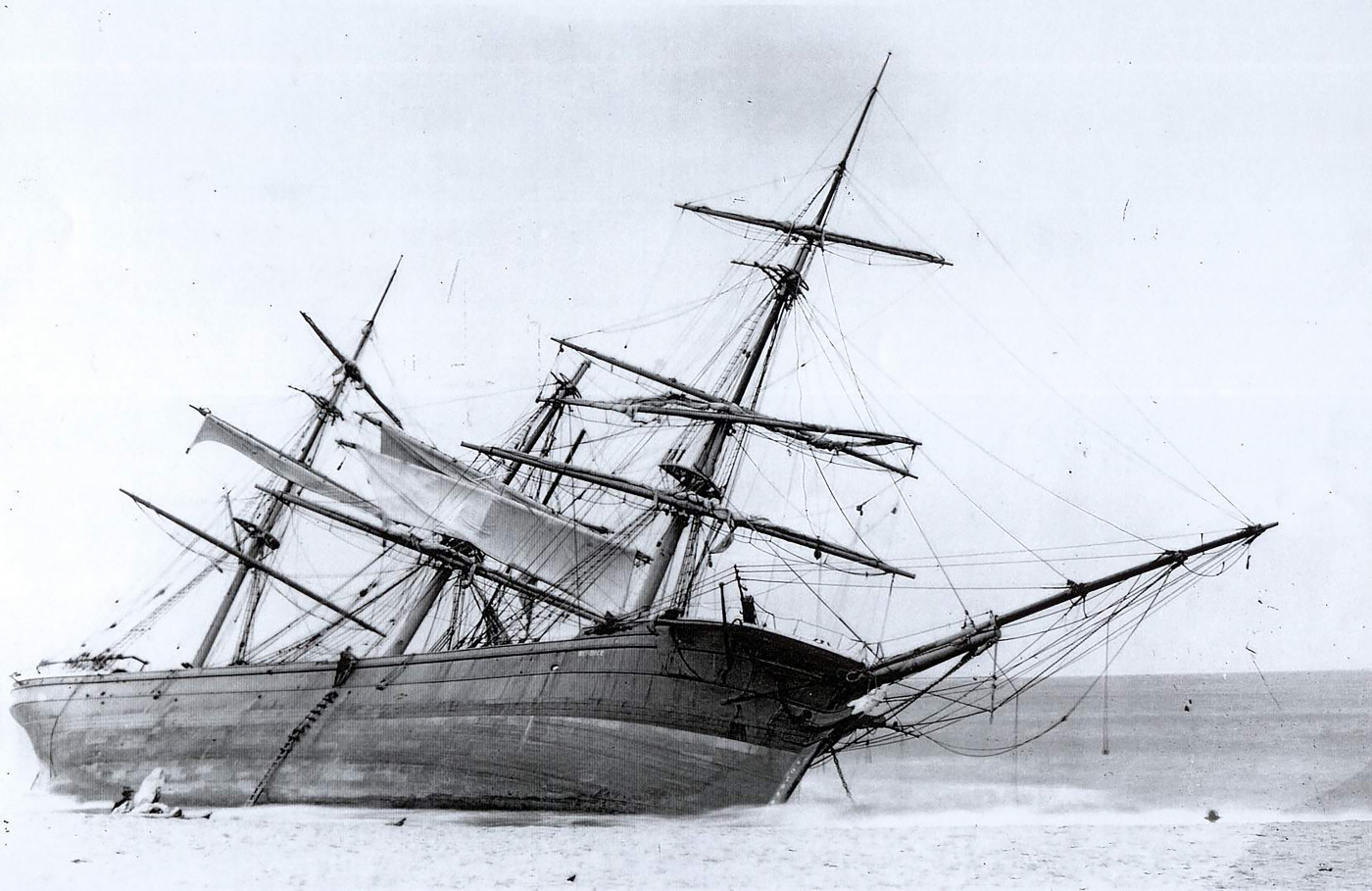

Berbice at Stockton Beach shortly after being driven ashore. Image: University of Newcastle Library Special Collections.

Ross then made the fateful decision to enter the river without a pilot and at first it appeared his gambit might be successful. With a following wind and all sails set, Berbice quickly moved towards the port, but refused to answer its helm as it rounded Nobbys. After several frantic attempts to bring the ship around, the crew let go an anchor, which immediately began to drag, effectively sealing its fate. Within moments, Berbice struck the Oyster Bank in almost the exact same spot as three other wrecked vessels: Lismore (1866), Rialto (1870) and Susanne Godeffroy (1880). As the crew huddled on the stern paralysed by fear, the ship was swept off the Oyster Bank by heavy seas and grounded on Stockton Beach a short time later. More rockets were launched, but this time were answered by the gun at Nobbys signal station, as a lifeboat set out to the crippled vessel. Ultimately, a rescue line fired from shore was attached to Berbice, and a breeches buoy (a rope-based rescue device) successfully employed to save the entire crew. As daylight dawned, the ship was found firmly embedded in sand and nearly high and dry at low tide 9. Within weeks, its wrecked hull was heeled far over to port and became a beachside attraction for Stockton locals. Captain Ross did not fare well either: he was severely censured by the Marine Board of New South Wales for recklessly attempting to enter a dangerous port without a pilot 10.

Berbice’s wrecked hull soon became a popular attraction for visitors to Stockton Beach. Nobbys Head is visible in the background right of the photograph. Image: University of Newcastle Library Special Collections.

History repeated itself – under somewhat different circumstances – seven years later, when Durisdeer approached the entrance to the Hunter River on the night of 22 December 1895. The barque had voyaged from Simon’s Town, South Africa to Newcastle in ballast, and was being towed towards the port by the tug Stormcock, which had picked it up off Sydney Heads the prior afternoon. Foul weather and a heavy sea pounded the two vessels as they rounded the south breakwater, but it appeared Durisdeer would make the entrance when it was struck by a sudden squall that caused the towline to part. As the barque was carried towards the Oyster Bank, its captain, John Webster, ordered a bower anchor dropped. For a moment, it appeared crisis was averted, but a sudden jerk as the anchor became fouled caused its cable to part with a resounding bang. A second anchor was quickly let go but it was too late: Durisdeer struck the Oyster Bank and was forced across it as the crew looked on in horror as it passed the wreck of the steamship Colonist, which had been lost in nearly the same location the previous year 11.

Durisdeer aground at Stockton Beach on 23 December 1895. Image: Newcastle Regional Library.

As Durisdeer traversed the Oyster Bank, the force with which its hull crashed against the seabed steadily increased in violence until the crew were unable to remain on their feet. Incredibly, the second anchor cable held, but the anchor itself dragged until the cable parted around 4 am on 23 December. Huge seas carried Durisdeer towards Stockton Beach, where it eventually grounded broadside to the shoreline and was struck by waves that broke completely over the hull. The barque’s crew had launched rockets and burned blue lights as soon as Stormcock’s towline parted, and while the signal station lifeboat was unable to safely reach the wreck, Stockton’s Rocket Brigade was able to deploy a breeches buoy from the beach and save all 18 men in just over 30 minutes 12.

Within days of wrecking, Durisdeer had fallen over on its port beam. Image: Newcastle Regional Library.

Although apparently undamaged during the wrecking event, Durisdeer began heeling steadily over to port in the surf, and by the afternoon of 24 December had fallen on its beam ends and started to break up. By the following weekend, the wreck had become a popular attraction, with scores of people cramming ferries to Stockton to see it firsthand. The town’s Carlisle Street, which had only recently been constructed, allowed these visitors easy access, and the more courageous were able to walk almost all the way to the barque’s crippled hull 13.

Like that of Berbice seven years earlier, Durisdeer’s wrecked hull became a popular drawcard for visitors to Stockton Beach. Image: Newcastle Regional Library.

An area as densely populated with historic shipwrecks as the Oyster Bank and Stockton Beach can create problems when it comes to the identification of specific wreck sites. As noted above, multiple shipwrecks are known to have occurred in the immediate vicinity of the locations where Durisdeer and Berbice were lost. In other locations, such as parts of the Oyster Bank, the density of accumulated shipwrecks was so great they literally piled on top of one another. This is perhaps best represented by the French barque Adolphe, which was swept onto the bank on 30 September 1904 during inclement weather and grounded on the wrecks of Lindus (1899), Wendouree (1898), Colonist (lost in 1894 and the same wreck observed by Durisdeer’s crew when it struck the Oyster Bank), and Cawarra (1866).

The French four-masted barque Adolphe aground on the Oyster Bank, October 1904. The mizzenmast of the wrecked iron barque Regent Murray (1899) is visible in the foreground. Image: University of Newcastle Library Special Collections.

Ultimately, these and a multitude of other wrecked vessels that extended out to sea in a rough line from Pirate’s Point formed the ‘foundation’ of the northern breakwater that now borders the entrance to the Hunter River 14.

Several shipwrecks, including Adolphe (far left), the hulk Elamang and Regent Murray (far right), formed the ‘foundation’ of the northern breakwater at the Hunter River’s entrance. Image: University of Newcastle Library Special Collections.

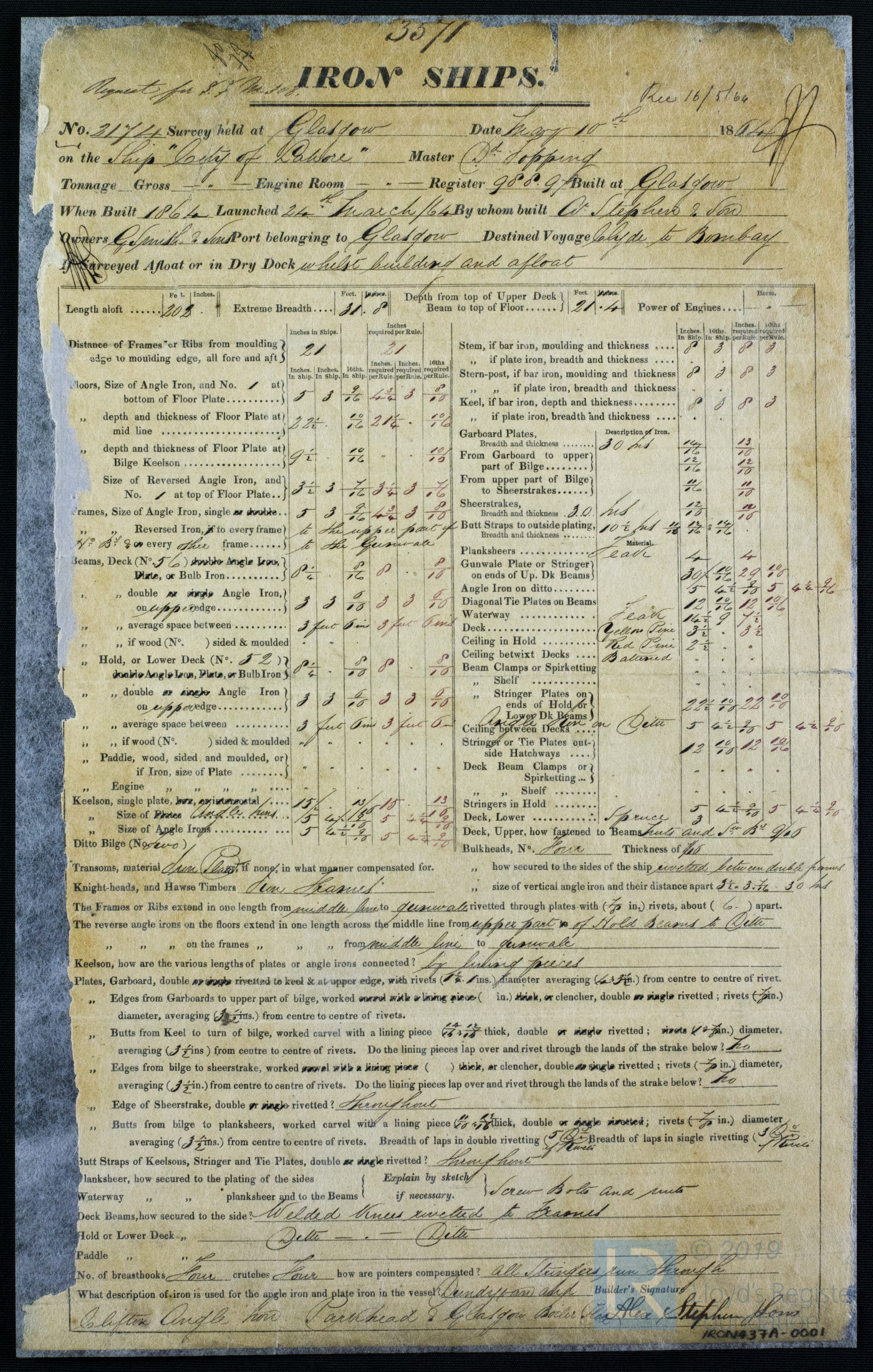

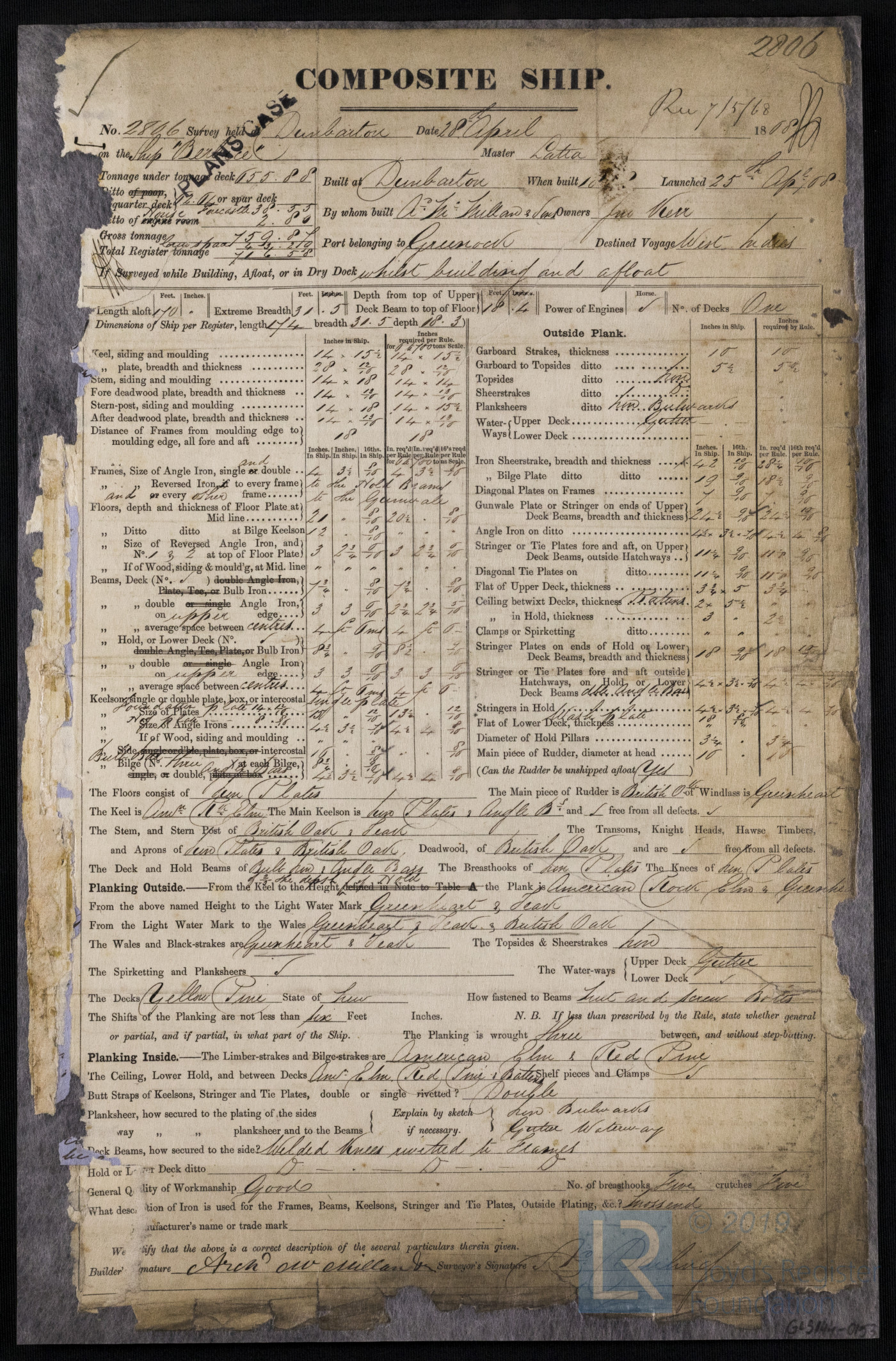

With so many vessel losses of similar vintage in such a small geographical area, historical information constitutes a critical resource with which to identify specific shipwreck sites. Fortunately, in the case of Durisdeer and Berbice, the Lloyd’s Register Foundation has digitised and posted a sizeable collection of archival documents online, including first survey records that contain specific details about their respective design and construction. This information – which includes scantlings (individual measurements for hull timbers and iron architectural components), identified timber species used to construct various hull components, and notations about repairs and modifications – can be compared with hull measurements, timber samples and other archaeological data recovered from shipwreck sites to aid in their identification.

The Lloyd’s first survey report for City of Lahore (later Durisdeer) contains invaluable data that could be compared with the shipwreck site. Image: Lloyd’s Register Foundation.

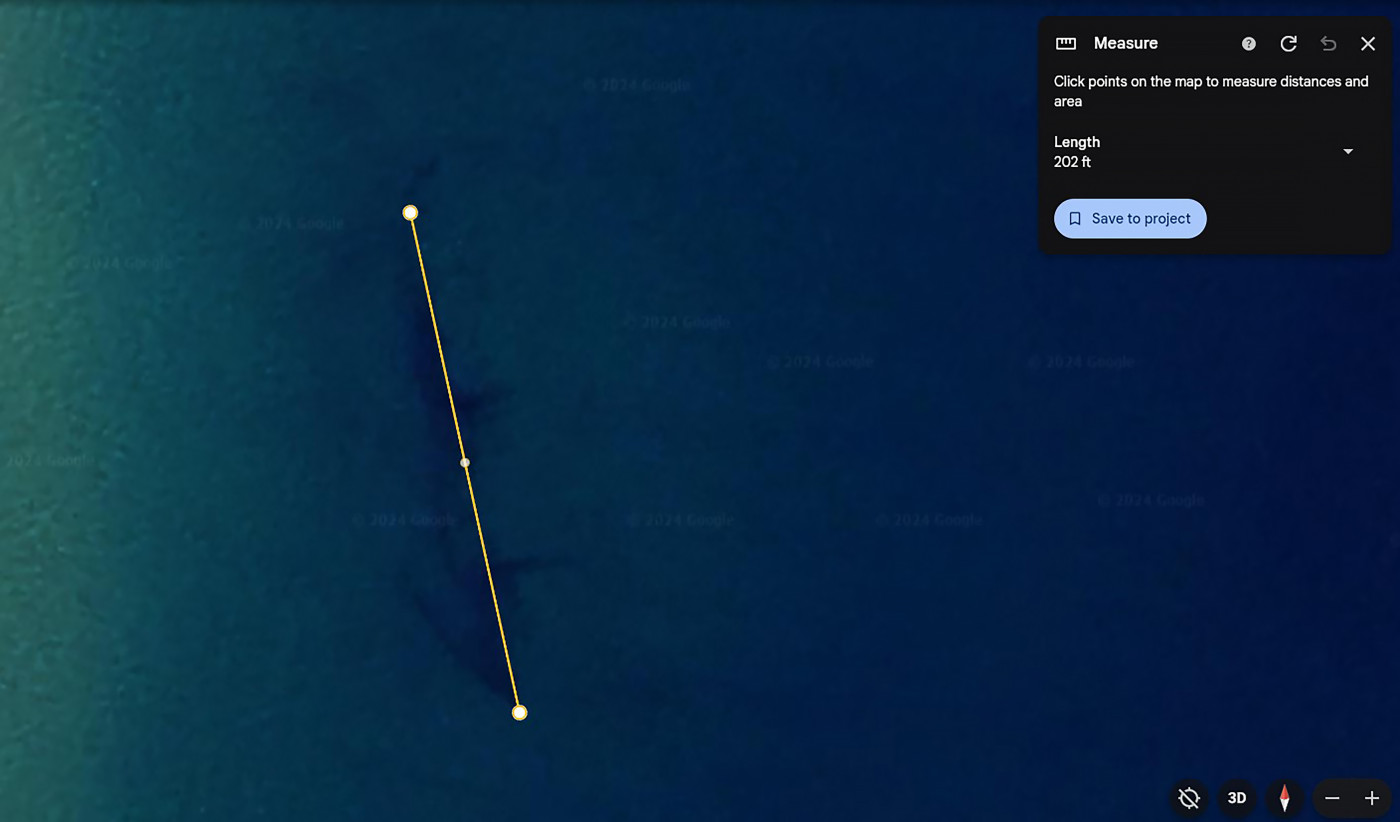

While Durisdeer and Berbice have yet to be archaeologically investigated, information available in Lloyd’s Register’s survey documents correlates well to observations collected by recreational divers, who have visited both shipwreck sites, as well as data derived from open access tools such as Google Earth. For example, Durisdeer’s recorded overall length of 61.6 m in Lloyd’s Register’s first survey report aligns exactly with the overall exposed length of the shipwreck when measured in Google Earth. Recreational divers have noted the wreck site lies heeled far over on its port side and its visible surviving hull is manufactured entirely of iron, as are the lower sections of the foremast and mainmast, which remain stepped in their original positions. These attributes of the hull’s construction are noted in the first survey report, and the wreck’s orientation matches archival photographs and descriptions recorded in the wake of Durisdeer’s loss.

Google Earth satellite image of the Durisdeer shipwreck site. The overall length of the exposed hull remains (202 ft, or 61.6 m) correlated exactly to Durisdeer’s ‘length aloft’ recorded in the Lloyd’s first survey report. Image: Google Earth.

While there is little doubt about the identity of the Berbice shipwreck site, given its location and composite construction, detailed documentation of its surviving hull would yield data to further solidify the conclusion. The Lloyd’s Register first survey report provides comprehensive scantling measurements that could be compared with those of the wreck’s surviving hull timbers and iron framing components. It also records diverse use of timber in the hull’s construction, including English oak (Quercus robur), teak (Tectona grandis), American rock elm (Ulmus thomasii), and greenheart (Chlorocardium rodiei). The latter two species, native to North and South America respectively, were used to construct Berbice’s lower hull planking ‘from the keel to the height of the hold’ and would be easily distinguishable from the British and European timber species more commonly used in mid-to-late 19th century ships built in Scotland. 15.

Intriguingly, Berbice’s first survey report also notes the ship was outfitted with an iron foremast and mainmast, and while these are not visible on site, they may have collapsed through the vessel’s timber hull and lie buried nearby off the wreck’s port side. Within the surviving hull, repairs and modifications noted in the ship’s 1882 survey – including the replacement of the ‘close ceiling’ (internal) planking with strakes hewn from ‘2 ½” pitch pine’ and the use of ‘earthenware pipes, fixed in cement…fitted at the limber holes at the middle line’ – could be specifically targeted and documented to establish additional evidence of the site’s identity 16.

The Lloyd’s first survey report for Berbice features unique construction, repair, and modification attributes that could be targeted and identified during an archaeological survey of the shipwreck site. Image: Lloyd’s Register Foundation.

The Australian National Maritime Museum plans to bring maritime archaeology to the Newcastle area by searching for and investigating historic shipwreck sites on the Oyster Bank and at Stockton Beach—a project that will include archaeological and 3D photogrammetric surveys of Durisdeer and Berbice. Updates on this initiative, including use of digitised archival material provided by the Foundation to secure identification of specific shipwreck sites, will feature in future posts. Stay tuned!

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the Lloyd’s Register Group or Lloyd’s Register Foundation.

Footnotes

-

1

Society for the Registry of Shipping. ‘City of Lahore’ (Entry No. 549), Lloyd’s Register of British and Foreign Shipping, 1865. Caledonian Maritime Research Trust. ‘City of Lahore’, Scottish-built ships: the history of shipbuilding in Scotland, 2024. https://www.clydeships.co.uk/view.php?ref=23486

-

2

Ibid.

-

3

Society for the Registry of Shipping. ‘Berbice’ (Entry No. 204), Lloyd’s Register of British and Foreign Shipping, 1869. Caledonian Maritime Research Trust. ‘Berbice’, Scottish-built ships: The History of Shipbuilding in Scotland, 2024. https://clydeships.co.uk/view.php?a1PageSize=75&year_built=&builder=&a1Page=119&ref=13780&vessel=BERBICE

-

4

Ibid.

-

5

W.J. Goold. ‘The Newcastle Lifeboat’ Royal Australian Historical Society Journal and Proceedings 31:3 (1945): pp. 164–195. Terry Callen, Bar Dangerous: A Maritime History of Newcastle. Newcastle Region Maritime Museum, 1986.

-

6

Callen, 1986, p. 20.

-

7

Callen, 1986; Cynthia Hunter. ”Shipwrecks about the entrance to Newcastle Harbour.” Coal and Community https://www.coalandcommunity.com/resources/Shipwrecks%20in%20Newcastle%20Harbour.pdf

-

8

Goold, 1945, p. 185.

-

9

Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners’ Advocate, 6 June 1888, p. 5.

-

10

Goold, 1945, p. 186. Callen, 1986, p. 142.

-

11

The Age, 24 December 1895, p. 5. Goold, 1945, p. 188.

-

12

The Age, 24 December 1895, p. 5. Callen, 1986, pp. 142–143.

-

13

Goold, 1945, p. 189.

-

14

The Argus, 4 October 1904, p. 5. Goold, 1945, pp. 192–193. Callen, 1986, pp. 134–136, 170–173.

-

15

Society for the Registry of Shipping. ‘First survey report: Ship Berbice (28 April)’, 1868. Lloyd’s Register Foundation Heritage & Education Centre https://hec.lrfoundation.org.uk/archive-library/documents/lrf-pun-gls144-0153-r

-

16

Ibid.