Of all the measures and devices for ensuring safety at sea, it can be argued that one of the most familiar to the general public is the life jacket, also known as a life vest. A simple foam or inflatable device that is secured around the shoulders and torso, it helps the wearer stay afloat in water, while its bright colours help in search and rescue. Because of its simplicity and effectiveness, the humble life jacket can be found anywhere from tour boats to airplanes, from kayaks to naval ships. Any time a person must be on water, one can almost guarantee a life jacket is on them or not too far from them. But how did such a ubiquitous safety device come to be? What steps did it go through to reach its modern form?

The first mention of something resembling a life vest comes in a 1763 treatise Tutamen Nauticum: Or, the seaman's preservation from shipwreck, diseases, and other calamities incident to mariners by John Wilkinson, M.D. Within it, he appeals to shipowners to take measures to preserve the lives of men aboard their ships. Among some of the things he proposes is a jacket lined with cork to enable a shipwrecked sailor to float for hours, even if the sailor could not swim 1. The last part was especially vital; at the time, few mariners knew how to. The cork life jacket is considered to be the first early model of life jacket and remained the standard material for the next 150 years.

While cork was standard, it was not the only option on the market. In 1806, Francis Columbine Daniel presented an inflatable life preserver to the Royal Humane Society. It consisted of a jacket which could be inflated with a silver tube. To promote his invention, Daniel arranged live demonstrations, in which people wearing his life preserver jumped into the water where they floated while doing such things as smoking a pipe or firing a pistol 2. However, these were more expensive than the simpler cork floatation devices. Furthermore, Daniel was a controversial man with many detractors who were quick to denounce him and his invention. Inflatables had to wait before they got their time in the limelight.

The next evolution of the life jacket came in 1854, when Captain Ward, an inspector for the Royal National Lifeboat Institute (RNLI) refined the cork life jacket. Instead of having the cork in one block, he divided them into narrow strips sewn into canvas. They were generally well-liked by RNLI crews and were quickly adopted 3 . RNLI lifeboats were thus manned by men wearing these jackets and carried spares to put on drowning victims to help them float. As proof of how good these cork vests were at saving lives, in 1861, when an RNLI lifeboat from Whitby capsized while out on rescue, there was a single survivor: Henry Freeman, the only one to wear a life jacket 4. It was a perfect demonstration for the effectiveness and need for such a device. This revaluation came independently to others, including lawmakers. Almost a decade before widespread use in the RNLI, in 1852, the United States Congress passed a law requiring all steamships to carry, among other things, enough life preservers for all passengers aboard the ship 5.

However, for all its good points, problems with the cork life jacket soon became apparent. They were bulky, heavy things that required regular replacement of the cork to stay buoyant. This was tragically demonstrated in the fire and sinking of the paddle steamer General Slocum in 1903, which killed 924 people. In an attempt to escape the fire, passengers grabbed life vests, only to find the cork inside had turned to dust, or worse, had been replaced with iron during manufacturing 6. The weight made such defects easy to hide. However, the biggest issue with cork life jackets, seen on board General Slocum, and later disasters such as the Titanic, is that when people were forced to jump from height into water, the cork could bob up so suddenly upon contact that it knocked out the wearer, leaving them vulnerable 7. As technology advanced, a better solution became possible.

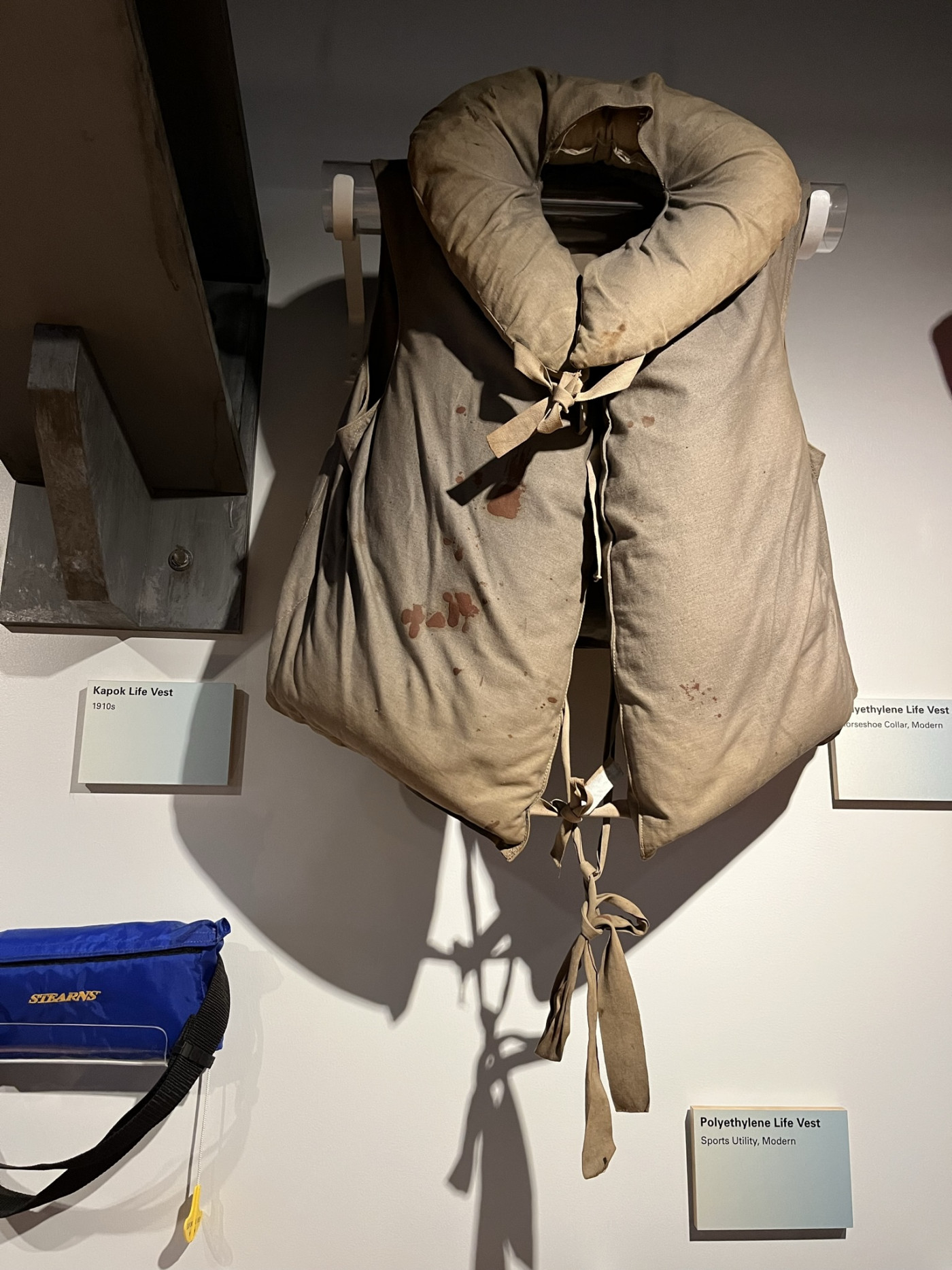

Kapok vest from 1910 on display the National Museum of the Great Lakes. Licensed under Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons. Credit to the original photographer user Mbrickn.

Orpheus Beaumont, a woman from New Zealand, created a jacket made from cotton filled with kapok, a lightweight plant fibre. She called it ‘Salvus’, and after refinement, it was accepted by the British Board of Trade in 1918 8 and became the standard life jacket until the Second World War. Kapok mainly came from Java, in the East Indies, and it became significantly more difficult to acquire during the war 9. The time had come for rubber inflatable life jackets to shine, especially in the Air Force, as pilots could store them easily in cramped cockpits and inflate them when needed. They were often nicknamed ‘Mae West’ as they made pilots wearing them look top-heavy, much like the voluptuous Hollywood actress of the same name 10. Their main advantage over a life belt was they kept the head above water, even if the wearer was unconscious; a common hazard for a crashing pilot.

Staff Sergeant Frank T. Lusic preparing for a bomber mission, 1943. Note the inflatable life vest as part of his flight gear. World War II In View, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

These inflatable jackets remain popular with some recreational boaters and on planes today. Pay attention to a safety demonstration on board any commercial aircraft; the yellow jackets with red toggles are an advanced form of the Second World War inflatable design. Inflatable life vests these days inflate automatically and are preferred by those who are not expected to be in water frequently.

Inflatables are not the only current option for life jackets, however. Developments in material science in the 1960s created a lightweight, flexible and highly buoyant foam. The RNLI, ever at the forefront of life jacket technology, began using the foam Beaufort life jacket in 19723. Foam is a more flexible material, and can be combined with inflatables, allowing life jackets to be made for children or even pets, increasing safety all around. The flexibility allows for greater freedom of movement in an emergency. At the same time, laws have also evolved. The United States, for example, mandates life jackets for all children under 13 on vessels in motion, while many states require life jacket wear while water skiing or sailboating 11.

Life jackets available for public use in Dinosaur Valley National Park, Texas, United States. Hu Nhu, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons.

It must be noted, however, that not all countries have such laws. In the United Kingdom, life jacket wear is only recommended. However, given how comfortable and easy to wear most modern life jackets are, it would be silly not to wear something that could save one’s life. We have come a long way from heavy cork and bulky kapok. Such innovation should be acknowledged and appreciated.

French bulldogs in the sea wearing life vests. Modern life vests are light and flexible enough for small dogs such as these. W. Carter; CC0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the Lloyd’s Register Group or Lloyd’s Register Foundation.

Footnotes

-

1

Wilkinson, John. Tutamen Nauticum: Or, the seaman’s preservation from shipwreck, diseases, and other calamities incident to mariners. 2nd ed., Messrs Dodsley, London., 1763. p.8. Accessed via Internet Archive https://archive.org/details/bim_eighteenth-century_tutamen-nauticum-or-th_wilkinson-john-md_1763/mode/2up.

-

2

Ellis-Rees, William. “The man who stole a knighthood: The story of Francis Columbine Daniel.” London Overlooked. 27 January 2019. https://london-overlooked.com/franciscolumbinedaniel/.

-

3

RNLI .“1854: First lifejackets.” Accessed 18 June 2024. https://rnli.org/about-us/our-history/timeline/1854-first-lifejackets .

-

4

Pickthall, Barry. A history of sailing in 100 objects. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2016. p.66.

-

5

The Library of Congress. “Acts of Congress relating to steamboats, collated with the rolls at Washington”. 1867. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, www.loc.gov/item/09011200/ p.13, section 5.

-

6

Houghtaling, Ted. “Witness to tragedy: the sinking of the General Slocum.” 24 February 2016. New York Historical Society. www.nyhistory.org/blogs/witness-to-tragedy-the-sinking-of-the-general-slocum.

-

7

Dunkirk 1940. “Life jackets.” Accessed 18 June 2024. https://dunkirk1940.org/index.php?&p=1_488

-

8

Holliday, John. “The history of Tiree in 100 objects - No. 64 The ‘Salvus’ life jacket.” An Tirisdeach. Accessed 18 June 2024. www.aniodhlann.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/object-no.-64-salvus-life-jacket.pdf

-

9

Holden, A. L., Lieutenant Commander. “Buoyant materials for navy life preservers in World War II.” October 1946. From Proceedings Journal, U.S. Naval Institute, Vol.72/10/524. www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/1946/october/buoyant-materials-navy-life-preservers-world-war-ii

-

10

National Naval Aviation Museum. “Mae West - vest.” Accessed 18 June 2024. www.history.navy.mil/content/history/museums/nnam/explore/exhibits/online-exhibits---collections/marine-corps-aviation-centennial/mae-west---vest.html

-

11

USCG Boating, U.S. Coast Guard. “Life jacket wear / wearing your life jacket.” Accessed 18 June 2024. https://uscgboating.org/recreational-boaters/life-jacket-wear-wearing-your-life-jacket.php.