The sight and sound of seabirds have always alerted mariners approaching land, but what is surprising is the link between seabirds, safety, shipwrecks, ladies’ hats, shooting and the 1869 Act for the Preservation of Sea Birds.

During the pandemic we embarked on a research topic that had long been of interest – the role of birds in social history. It was published as When There Were Birds: The Forgotten History of Our Connections.1Connections with the sea were plentiful, but what took us aback was that in the 19th century seabirds around the British Isles were so endangered that shipwrecks were caused.

In times past the raucous cries of thousands of seabirds generated comment by travellers. Gulls and other seabirds were abundant, far more than today, with a substantial increase in some areas during the breeding season. 2 In July 1769 the Welsh naturalist Thomas Pennant was in the East Riding of Yorkshire, and he described being taken in a small boat to view Flamborough Head from the sea:

The cliffs are of a tremendous height, and amazing grandeur ... the color of all these rocks is white, from the dung of the innumerable flocks of migratory birds, which quite cover the face of them, filling every little projection, every hole that will give them leave to rest; multitudes were swimming about, others swarmed in the air, and almost stunned us with the variety of their croaks and screams. 3

Sailing boats at Flamborough

Flamborough seabirds

When There Were Birds

Sailing boats at Flamborough

Flamborough seabirds

When There Were Birds

Seafarers relied on the sound of seabirds to warn them of dangers ahead, particularly when fog and mist enveloped landmarks and lighthouses. The Nautical Magazine in 1870 said of fog:

Buoys and beacons are of no use for they cannot be seen at all, and lights are only visible at short distances. The only remaining resource is sound ... On the rough Welsh coast are the homes of innumerable sea-birds, and on the extreme edges of the rocky ledges and cliffs these birds in vast numbers perch themselves and lift up their voices. Their shrill screams and cries are heard for miles out at sea, and even above the noise of winds and water their clamour is often heard. The strange shrieks of these wild birds are frequently very comforting to the navigator when his vessel is enveloped in mist. 4

Twenty years before, in 1850, John Wolley, a naturalist, had advised that anyone involved in coastal navigation should be concerned about seabirds, so that ‘one of the best kinds of beacons, the flight and clamour of birds, be preserved, to warn vessels in foggy weather of their approach to the dangerous headlands of our coast’. 5 He said that seabirds were valued at a few lighthouses, one of which was South Stack off the north-west coast of Holyhead Island, Anglesey. About a year earlier, Charles Frederick Cliffe, the owner and editor of the Gloucestershire Chronicle, was in north Wales and visited this lighthouse:

The sea in S.W. gales often dashes over the dwellings of the lightkeepers, when the scene is sublime. This coast is the resort, in the breeding season, of innumerable sea-birds––especially gulls, razor-bills, cormorants, and guillemots ... No one, by order of Government (Trinity House), is allowed to shoot the sea-birds, as in foggy weather they are invaluable to steamers and shipping, being instantly attracted round a vessel, or induced to fly up screaming, by the firing of a gun. 6

North Wales and Merseyside in 1856

South Stack lighthouse

North Wales and Merseyside in 1856

South Stack lighthouse

A newspaper in 1868 reported that visitors could see prodigious numbers of seabirds at South Stack, and they were always audible, whatever the weather conditions:

It has been ascertained that in thick weather, when neither light can be distinguished nor signal seen, the incessant scream of these birds gives the best of all warnings to the mariner, of the vicinity of the rock. The noise they make can be heard at a greater distance than the tolling of the great bell (at North Stack); and so valuable was this danger signal considered, that an order from the Trinity House forbade even the firing of the warning gun, lest the colony of the sea-fowl should be disturbed. 7

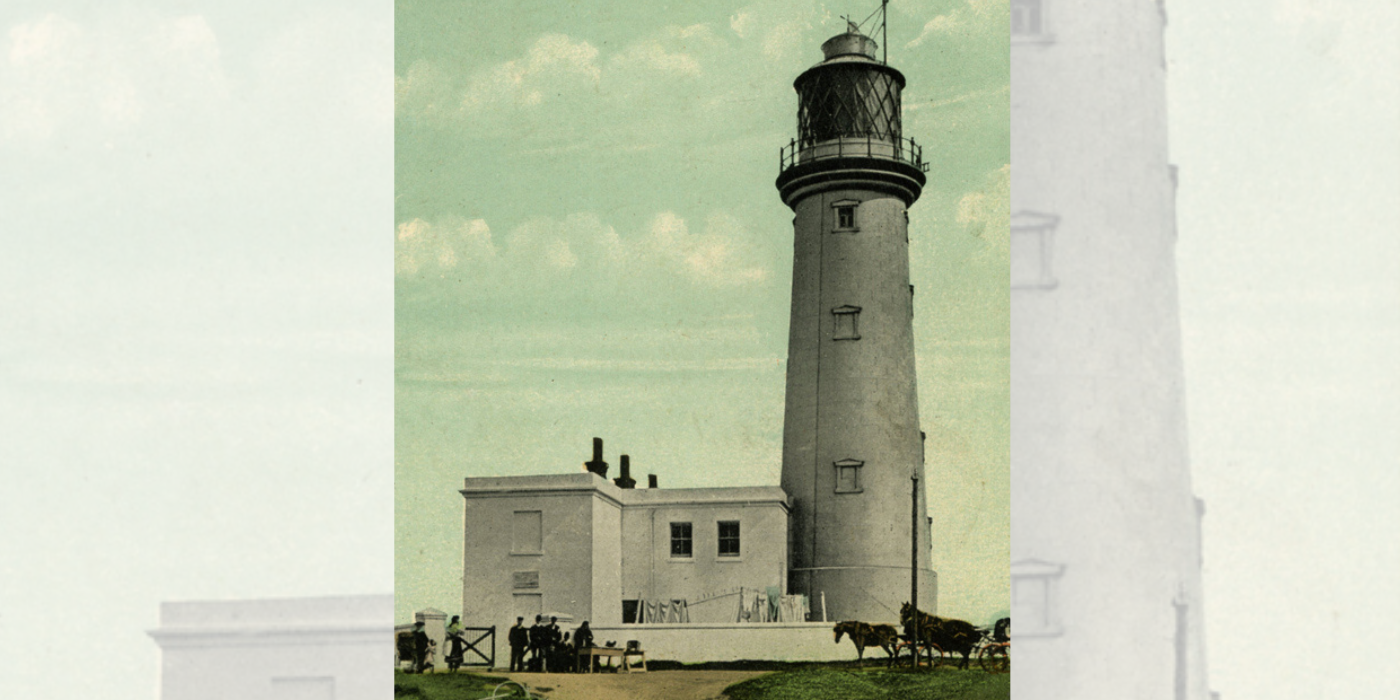

Jutting out into the North Sea from the East Yorkshire coast, Flamborough Head was a notorious hazard to coastal shipping, and according to one local naturalist, ‘Woe betide the unhappy sailors whose vessel is caught in the cruel fangs masked by those breakers. Their vessel is crushed like an egg shell in the grip of a giant, and they are hurled into eternity before any means of rescue can be devised’. 8 Francis Orpen Morris was vicar at nearby Nafferton from 1844, before moving further inland to Nunburnholme a decade later. 9 He was the son of a Royal Navy admiral, a naturalist, campaigner and prolific author, especially on birds. He explained that although a lighthouse at Flamborough Head had been built in 1806, gulls were nevertheless needed to guide vessels to safety in fog:

When the sea roke (the Yorkshire word for sea-fog or mist) closes in round the becalmed vessel which is helplessly drifting on towards the dangerous shore, and even the bright Flamborough revolving light cannot be seen, the harsh screams of ten thousand sea-gulls are as useful to the crew as the far-famed Inchcape bell, and they may well bless these ‘Flamborough Pilots’ and hail their cry. 10

Flamborough Head on a map of 1722

Flamborough lighthouse in 1909

Flamborough Head on a map of 1722

Flamborough lighthouse in 1909

Edward Anderson was brought up near Weaverthorpe in the East Riding and later at Kilham, a few miles from Flamborough, which he knew well. He spent his working life at sea and ended up as master of the Jemima, trading between London and Lisbon. 11 He later became a Methodist preacher and around 1803 published an autobiographical poem, which he subsequently expanded and republished as The Sailor. This later version mentioned Flamborough:

Oft in the night I careful hove the lead,

As we our course did steer past Flambro Head;

Thick weather, when afraid to come too nigh,

Then we observ’d which way the birds did fly;

When at a distance, and no land in sight,

The birds our pilots, they direct us right. 12

Heaving the lead was done with a line and lead weight and for generations was the only reliable method of checking the depth of water when approaching the coast. 13 It was also mentioned by Thomas Waller. Like Anderson, he too grew up at Kilham, but later became a schoolteacher at Greenwich, near London. In 1869, after reading about the threat to seabirds at Flamborough Head, he wrote letters to various newspapers, explaining why north-country seamen called seabirds ‘Flambro’ Head Pilots’:

The most dense fog and the darkest gloom make no difference to these birds in their flight, and it is by observing the direction of their flight, and the use of his lead, the bewildered mariner knows his exact position. During the spring months, when that truly dangerous headland is most frequently enveloped by the sea fog and its dangers increased manifold, at that very time a kind Providence has peopled it by those invaluable ‘Flambro’ Head Pilots.’ 14

Coastal and island communities had long treated seabirds as a resource, relying on them for meat, eggs, oil and feathers, and from St Kilda to the Isle of Wight men and boys collected eggs from the sheer cliffs to eat or to sell to collectors. Bird numbers declined when many more eggs were also gathered for the sugar and leather industries. 15 The advance in gun technology in the 19th century was especially damaging, while railways enabled countless sportsmen and tourists to reach the coast with ease and kill seabirds. Christopher Sykes, Member of Parliament for the East Riding, blamed the ‘thoughtless pleasure seekers ... who flocked to the coast in summer months, chiefly from the populous towns of the West Riding of Yorkshire and Lancashire’. 16 According to John Cordeaux, an ornithologist from Lincolnshire, the reckless and indiscriminate killing of seabirds was driven mainly by betting on shooting matches. 17

John Hodgson descending the cliffs near Flamborough, Yorkshire

Egg gatherers at Flamborough

John Hodgson descending the cliffs near Flamborough, Yorkshire

Egg gatherers at Flamborough

By the mid-19th century, huge quantities of birds were also being killed for the millinery industry. 18 The need for feathers for decorating ladies’ hats worldwide was insatiable, and in Britain kittiwake feathers were favoured, as Cordeaux explained: ‘The young kittiwake is particularly in request by these feather-makers, as the rich black markings on the plumage contrast favourably with the pure white of the under parts and pearl-gray of the back.’ 19 While visiting Flamborough in October 1867, he learned about the shooting:

Many hundreds of kittiwakes were seen about the headland on the 14th and 15th, and I was told that on the latter day upwards of one hundred were shot and brought in by one boat. I deeply regret to write that this graceful and trustful gull is threatened with speedy extinction at this famous breeding-place; thousands have been shot in the last two years to supply the ‘plume trade.’ The London and provincial dealers now give one shilling per head for every ‘white gull’ forwarded ... One man, a recent arrival at Flamborough, boasted to me that he had in this year killed with his own gun four thousand of these gulls. 20

In the 1860s it was firmly believed that the massacre of seabirds was contributing to an increase in shipwrecks, even though there may have been other factors. The Yorkshire Gazette on 1 March 1862 reported two disasters in fog:

The brig Isabella, Captain Whitton, of and bound for Hartlepool, from Dieppe, ran on the rocks, near the extreme point of Flamborough Head during a dense fog, on Saturday last, about four p.m. She drove up on the following tide and remains. She is considerably injured, but may possibly be got off, should the weather be favourable.—On the following morning, the billy-boy Metcalf, Captain Pakey, bound from Stockwith to Sunderland, ran on the rocks very near to the above vessel, it being very foggy. She is laden with oak timber, which is being salved. The vessel has received very considerable damage, and will probably become a wreck. 21

In October 1867 Cordeaux described another incident in fog at Flamborough after he had returned to his lodgings: ‘That night an 800-ton barque went on shore within a quarter of a mile of the light-house. It proved a fortunate circumstance for the fishermen, who got £200 for getting her off the rocks, which, thanks to the high spring tide, they did before morning, and £35 more for taking her to Sunderland.’ 22 The newspapers gave additional information:

The barque Oceola, Pearson, of Scarborough, from London for Shields, ran ashore at 11 p.m. 14th inst. on the south point of Flamborough Head, and was assisted off by Flamborough fishermen at 5 a.m. to-day. She lost her false keel, her boat was smashed, and she left three kedges and a broken warp, and has probably received considerable damage. 23

The Oceola wooden sailing barque under Captain T. Pearson was lucky to avoid being wrecked. Constructed in 1863 by Alfred Simey & Co. at Sunderland, she was classed as ✠A1 in Lloyd’s Register of British and Foreign Shipping, which also recorded a length of 108.5 feet, breadth 26.0 feet and depth 16.2 feet. The net tonnage (cargo capacity) was 289, and the vessel was registered at Scarborough. The Maltese cross prefix, introduced in 1853, showed that she had been constantly surveyed throughout construction under Lloyd’s Register Special Survey. The Register also indicated that the damage was repaired in late 1867. 24

In 1868 several clergymen, naturalists and landowners in East Yorkshire formed a committee to campaign against the seabird decline. Richard Wilton, rector of Londesborough, was inspired to write a poem, imagining how those on board a bark, approaching at night in the thick mist, are unable to see the revolving white and red lights of Flamborough lighthouse or hear the guns on shore. Suddenly, one of the crew hears the seabirds, a sign of nearby land:

‘The Flamborough pilots,’ is his cry;

Beware, beware: the rocks are nigh:

Turn the ship’s head, and seaward fly.

Wilton then compares these birds with angels, who save the helpless vessel. He ends his poem with the mist clearing at dawn, at which point several boats appear, filled with daytrippers who begin shooting the birds. By this folly, they directly cause even more shipwrecks at the foot of the chalk cliffs:

O cruel sound, O piteous sight:

The gentle pilots of the night

Are murdered with the morning-light.

And lo! for lack of warning call,

Ships lost beneath that white sea-wall,

Where now the ‘Flamborough pilots’ fall. 25

Francis Morris wrote to The Times in January 1869 about the slaughter of gulls around the coast, particularly at Flamborough, where he himself had witnessed numerous shipwrecks. He called for the massacre of gulls to be stopped.

Boatloads of men shooting birds at Flamborough

Rough Sea at Flamborough

Boatloads of men shooting birds at Flamborough

Rough Sea at Flamborough

In London the Daily News was one of many newspapers concerned about wildlife, and it reported how in 1867 an Act was passed on the Isle of Man to protect gulls:

The Manx authorities obtained a special Act of Parliament—not, indeed, to prevent ladies from wearing feathers in their hats, but to prevent the destruction of sea-birds on the coasts of the Isle of Man. And the reason they allege for desiring the preservation of the birds will perhaps seem to many as surprising as the cause of the birds’ destruction. It appears that the cries of the birds are a more effectual warning to seamen of the dangers of a rock-bound coast than light-houses or fog-bells. 26

In February 1869 an Act for the Preservation of Sea Birds was introduced to the House of Commons by Christopher Sykes. According to him, the Act was not simply for the welfare of the birds:

He appealed to the House also in the interest of our merchant sailors, for in foggy weather those birds, by their cry, afforded warning of the proximity of a rocky shore, when neither a beacon-light could be seen nor a signal-gun heard. He held in his hand a paper proving that with the decrease of those birds the number of vessels which had gone ashore at Flamborough Head had steadily increased. For the services they rendered to the mariner those birds had earned for themselves the name of the ‘Flamborough pilots.’ 27

On 10 March 1869 a meeting in London of interested parties discussed the provisions of the Act. The Honourable William Owen Stanley, Member of Parliament for Beaumaris and Lord Lieutenant for Anglesey, ‘spoke of the protection against shipwreck seabirds afforded on the coast, and read a letter in which the testimony of the brethren of Trinity House, to the same effect, was emphatically given’. 28 Stanley added that ‘if sailors of England were polled they would be found to be in favour of seabirds, on account of the warning of danger their presence often afforded’. The Act was passed later that year, in June 1869, making it illegal to wound, kill or attempt to kill various named seabirds, though only during the breeding season between 1 April and 1 August and excluding St Kilda. It was one of the earliest pieces of legislation to protect wild birds in the British Isles. 29

Two years afterwards, John Cordeaux returned to Flamborough and thought that the Act had satisfied most people, except for those in the millinery trade. Although the boatmen complained that shooters no longer hired their services, Cordeaux said that one boatman admitted to taking numerous visitors to see the breeding haunts of the seabirds:

My own opinion is that each year as the birds increase, greater and greater numbers of respectable people will be attracted to Flamborough for the pleasure of viewing the glorious scenery of the headland, with its countless feathered tenants. The element of rowdyism was too rampant in the old days of bird-slaughter to permit any real enjoyment of the fine coast scenery. 30

As bird numbers increased, shipwrecks must have been prevented. The actual number is impossible to state, but it was an invaluable lesson in taking care of the environment.

Welcome to Yorkshire: Discover Flamborough & Flamborough Head

Flamborough Head Lighthouse Visitor Centre

Flamborough Cliffs Nature Reserve

Footnotes

-

1

Roy and Lesley Adkins 2021 When There Were Birds: The forgotten history of our connections (London: Little, Brown), published in hardback, paperback, e-book and audiobook.

-

2

Ornithologists today tend not to use the term ‘seagull’, but simply ‘gull’, as many of them breed inland.

-

3

T. Pennant 1772 (2nd edn) A Tour in Scotland: MDCCLXIX (London: Benjamin White), pp. 15–16.

-

4

See pp. 569 and 572 of ‘Our Seamarks, No. 4.––Fog Signals’ in The Nautical Magazine and Naval Chronicle (1870), pp. 568–73.

-

5

See p. 117 of J. Wolley ‘Some Observations on the Birds of the Faroe Islands’ in William Jardine 1852 Contributions to Ornithology, 1848–1852 (London: Samuel Highley), pp. 106–17.

-

6

Charles Frederick Cliffe 1850 The Book of North Wales: Scenery, Antiquities, Highways and Byeways, Lakes, Streams, and Railways (London: Longman, Brown, Green, andLongmans; Bangor: W. Shone), p. 118. Trinity House is still responsible for safeguarding shipping and seafarers. Cliffe lived 1810–51.

-

7

The Christian Times 30 October 1868, p. 2.

-

8

See pp. 1–2 of E.W. Wade 1903 ‘The Birds of Bempton Cliffs’ in Transactions of the Hull Scientific and Field Naturalists’ Club 3 no. 1, pp. 1–26.

-

9

M.C.F. Morris 1907 Nunburnholme: its history and antiquities (London: Henry Frowde; York: John Sampson), pp. 128–31.

-

10

The Times 14 January 1869, p. 7. Francis Orpen Morris lived 1810–93. The Inchcape Rock, off the east coast of Scotland, is the site of the Bell Rock lighthouse.

-

11

Edward Anderson c.1803 Poems: A Description of a Shepherd; His going to Sea ... with observations on the town of Liverpool (Workington: W. Borrowdale), p. 4. Anderson lived 1763–1843. Kilham was roughly 12 miles from Flamborough.

-

12

Edward Anderson c.1804 The Sailor; A Poem. Description of his going to sea ... with observations of the town of Liverpool (Newcastle: M. Angus), pp.29–30. Another edition appeared in 1806 as The Sailor: A Poem, in five books (Liverpool: H. Forshaw) – see p. 35. See also Kentish Mercury 1 May 1869, p. 4 (where the poem’s date is incorrect).

-

13

I.C.B. Dear and Peter Kemp 2005 (2nd edn) The Oxford Companion to Ships and the Sea (Oxford University Press), pp. 312–13.

-

14

Kentish Mercury 1 May 1869, p. 4. Thomas Waller was born at Kilham in 1810.

-

15

Adkins 2021, pp. 206–9; Wade 1903, pp. 20–4.

-

16

Hansard HC Debate vol. 194, cols 404–6, February 1869.

-

17

See p. 2825 of John Cordeaux 1871 ‘Flamborough and the Bird Act’ in The Zoologist 6 (2nd series), pp. 2822–8.

-

18

Adkins 2021, pp. 324–8.

-

19

See p. 1010 of John Cordeaux 1867 ‘Notes from Flamborough’ in The Zoologist 2 (2nd series), pp. 1008–11.

-

20

Cordeaux 1867, pp. 1009–10.

-

21

Yorkshire Gazette 1 March 1862, p. 3. The Isabella was condemned, and probably the Metcalf as well, though the cargo was salvaged (Newcastle Courant 7 March 1862, p.6)

-

22

Cordeaux 1867, p. 1009.

-

23

Shipping and Mercantile Gazette 16 October 1867, p. 4.

-

24

Lloyd’s Register of British and Foreign Shipping. From 1st July, 1867, to the 30th June 1868. For tonnage see David B. Clement 2021 Square-Rigger Sunset: The Passages of the four and five-masted ships and barques volume 1 (Exeter: The South West Maritime History Society), pp. 72–3.

-

25

The poem was written in December 1868 and published in The Church of England Magazine vol. 6, 8 May 1869, pp. 319–20. It was reprinted in several other magazines and newspapers.

-

26

The Daily News 13 March 1969, p.4.

-

27

Hansard HC Debate vol. 194, cols 404–6, February 1869. Also reproduced in The Hull Packet and East Riding Times 5 March 1869, p. 6.

-

28

The Leeds Mercury 12 March 1869, p.3.

-

29

The Act for the Preservation of Sea Birds 1869 was 32 & 33 Vict. cap 17.

-

30

Cordeaux 1871, p. 2826