A Marine Protected Area (MPA) is a conservation mechanism that aims to protect an area of ocean from human activity. There are over 16,000 marine protected areas worldwide. An MPA, which is self-established by states and other authorities, can take many forms. Most allow human activity; there are very few “no-take” zones that ban all human extraction and fishing. Last year, countries at the 2022 United Nations Biodiversity Conference (COP15) agreed to aim for protecting 30% of the ocean by 2030. MPAs currently cover 6% of the ocean.

In March 2023, Member States at the United Nations reached an agreement on a new instrument under the 1982 Law of the Sea Convention for the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity beyond national jurisdiction (BBNJ Agreement).

Pernille was with Thærie but Thærie disappeared, so Pernille found Konrad and they made babies. They were content for a season but then an interloper intruded, and Konrad was scared off. The bully moved in with Pernille, but she moved out and has not been seen since.

This underwater soap opera concerns ugly-beautiful wolffish. Beautiful, because of their grace in the water, their large bodies swishing as they move. Ugly, because have you seen their faces? These wolffish have names because of two facts: first, that they have chosen to live in the astonishingly beautiful and unique surroundings of Saltstraumen in northern Norway, a strait that is like no other in the world. The water flowing between inland Skjerstadfjord and outer Saltenfjord, combined with the depths and the width of the channel have made the world’s strongest tidal current. Every second, three metres3 of water hurtles through the 150-metre passage, sometimes at speeds of 20 knots. It produces the biggest maelstrom in the world. A maelstrom is a powerful whirlpool that sucks in objects.

In 2013, Saltstraumen became part of Norway’s 2,390 km2 of Marine Protected Areas (MPA) (out of a total sea area of 933,028 km2). MPAs are a method of ocean conservation that aims to limit human activity. There are 1,692 MPAs in European seas and ten times that number globally. Saltstraumen, an area of 24.7 km2 was proposed, according to the law setting it up, because it is “an area that has endangered, rare and vulnerable nature, represents certain types of nature and holds special scientific value.”

“MPA” is a label that conceals a massive amount of variability. Any government or authority can establish a Marine Protected Area. A good one is, in the words of marine conservationist Dr Callum Roberts, “leaky”. Protect the fish inside it, and they live longer and grow bigger and produce vastly more eggs, meaning more fish for everywhere. But in 2018, a paper by marine biologist Dr Boris Worm found that most MPAs were open to bottom-trawling, the most damaging form of industrial fishing. The following year, the conservation charity Oceana found that bottom trawling and dredging took place in 71 out of 73 of the UK’s MPAs. Professor Mark Costello, who ran the MPA workshop at Nord University, calculates that only a quarter of coastal countries have any marine reserves; and only 1% of the ocean is without fishing. In the Marine Conservation Society’s Marine Protection Atlas, Saltstraumen is in the “less protected/unknown” category, which designates “areas that afford some protection but allow moderate to extensive extraction and associated impacts”. This year, a paper by Veronica Relano and Daniel Pauly established a “paper park index”, using various criteria to decide whether a marine protected area was protected only on paper. They found plenty to populate their index.

Pernille (left) and Thærie (right)

Konrad guarding Pernilles eggs

For Borghild Viem and Fredric Ihrsen, who run the NORD&NE diving centre on the banks of Saltstraumen, their MPA is as flimsy as a paper park gets. In Saltstraumen, they tell me, only the kelp is protected. Fishing is allowed; underwater hunting is allowed; the discarding and abandonment of thousands of fish-strangling lines and hooks is allowed. The gathering up of the those hooks and lines though requires a permit which costs nothing except paper and hours of pointless bureaucracy.

I had met Borghild and Fredric the previous day, at a university workshop that launched a two-year EU project to establish the best methodology to decide the best places to site MPAs. Much of the day involved complex and technical science: Borghild and Fredric occasionally looked as mystified as I felt, and they were divers, the best underwater monitors we have, so I was drawn to them on both counts.

Nord&Ne divers over a kelp forest

A Nord&Ne diver collecting abandoned fishing lines and hooks

On the day I visit them at Saltstraumen, the weather is driving snow and cold. We are just above the Arctic Circle here, but this weather has surprised locals: they thought they were done with winter. I am pleased to be invited into the old wooden house that is the diving centre, to be given hot coffee and good dark chocolate, and to hear the story of the Saltstraumen wolffish who may be the salvation of this troubled MPA.

Wolffish – also known as catfish, devil fish and seawolves – are benthic bottom-dwellers, mostly they only move to eat, and although their faces are ones only a mother could love, their colours – a shimmering marine blue – are beautiful. And their behaviour is mesmerising, because once the female has laid eggs, the father guards them in his cave for 5 or 6 months, not eating and not moving. Carl Linnaeus named the fish after a wolf because of its impressive front teeth. They are long and muscular, and they are important predators because those teeth enable them to eat clams and the easily ubiquitous sea urchin, which I saw all over the sea floor in the Bay of Dakar because there are no fish left to eat them.

But wolffish are also tasty and in Saltstraumen underwater hunters come to fish them, usually stabbing them to death because they are large and stationary and literally sitting targets. This is why Borghild and Fredric decided to launch the wolffish soap opera. “We want to personify the MPA,” says Fredric, “so we make stories. The wolffish has been the red thread through the stories.” Their first wolffish was named Thærie, after a famous Henrik Ibsen poem. He initiated their wolffish education. “We suddenly met this, wow, it's a wolffish with eggs. Then we started to follow him.” By simple observation over time, Fredric and Borghild discovered a fact that had eluded marine biologists; wolffish mate for life, or at least try to. “We saw that it was the same lady who came back and then the next summer the same lady again.” They became experts on the lifecycle of Anarhichas lupus. Love-making in late autumn; in November, the eggs were laid, and then the “lady” leaves, no-one knows where. Thærie would stay put, barely moving, wrapped around the 5,000 or so eggs, until late April. “When the eggs are hatched,” says Borghild, “I guess Thærie is quite bored just lying in the cave, so he usually leaves, and the cave is empty. In June, he goes to and fro a bit, fixing the house, and in July the lady comes back. They stayed together four years. Year after year after year.”

Divers are meant to leave underwater wildlife in peace. You don’t touch, you don’t disturb. You only leave bubbles. So, it may be ironic that I come to think of Borghild and Fredric as being the most hands-on of environmental protectors. They understand that people will protect what they have come to love and often they love what they know, so after Thærie, they began to name their fish couples after Saltstraumen villagers from history. Pernille was a midwife; Konrad was a one-legged sailor who was custodian of the lighthouse. Parelius and Ida, another couple, were named for the village ferryman and his wife. (A bridge was built in 1978 to reduce the danger of the crossing.)

Pernille and Thærie’s love story ended in 2021. “Suddenly all the wolffish were gone,” says Borghild. There were underwater hunters in the area, and for a week all the wolffish caves were deserted. In the UK, the fish is called Scarborough Woof, and sometimes used in fish and chips. In the United States, the Atlantic wolffish is a species of concern; Canada calls it a “species at risk.” In the UK, using as a measure how many are caught as bycatch, wolffish have declined by 96% since 1889; in the US, the number of wolffish landed by commercial fishers dropped 95% from over 1,200 tonnes in 1983 to just 64.7 tonnes in 2007. There are no formal wolffish fisheries. Mostly they get trapped as by-catch: their bottom-dwelling habits make them prey for any trawling. A bottom-trawl is a sweep not a selection. Wolffish are vulnerable not just because they stay put but also because they mature relatively late and only breed after the age of seven or so. This means stock that is depleted takes longer than other populations to recover. A Scottish NGO (Non-Governmental Organisation) named Coastal Communities writes: “The wolffish therefore faces the worst of all worlds: It is being hunted to extinction by accident, and — unlike the tiger or the panda or the snow leopard — isn’t cute enough to have attracted any humans passionate enough to save it.”

A cod caught in fishing line

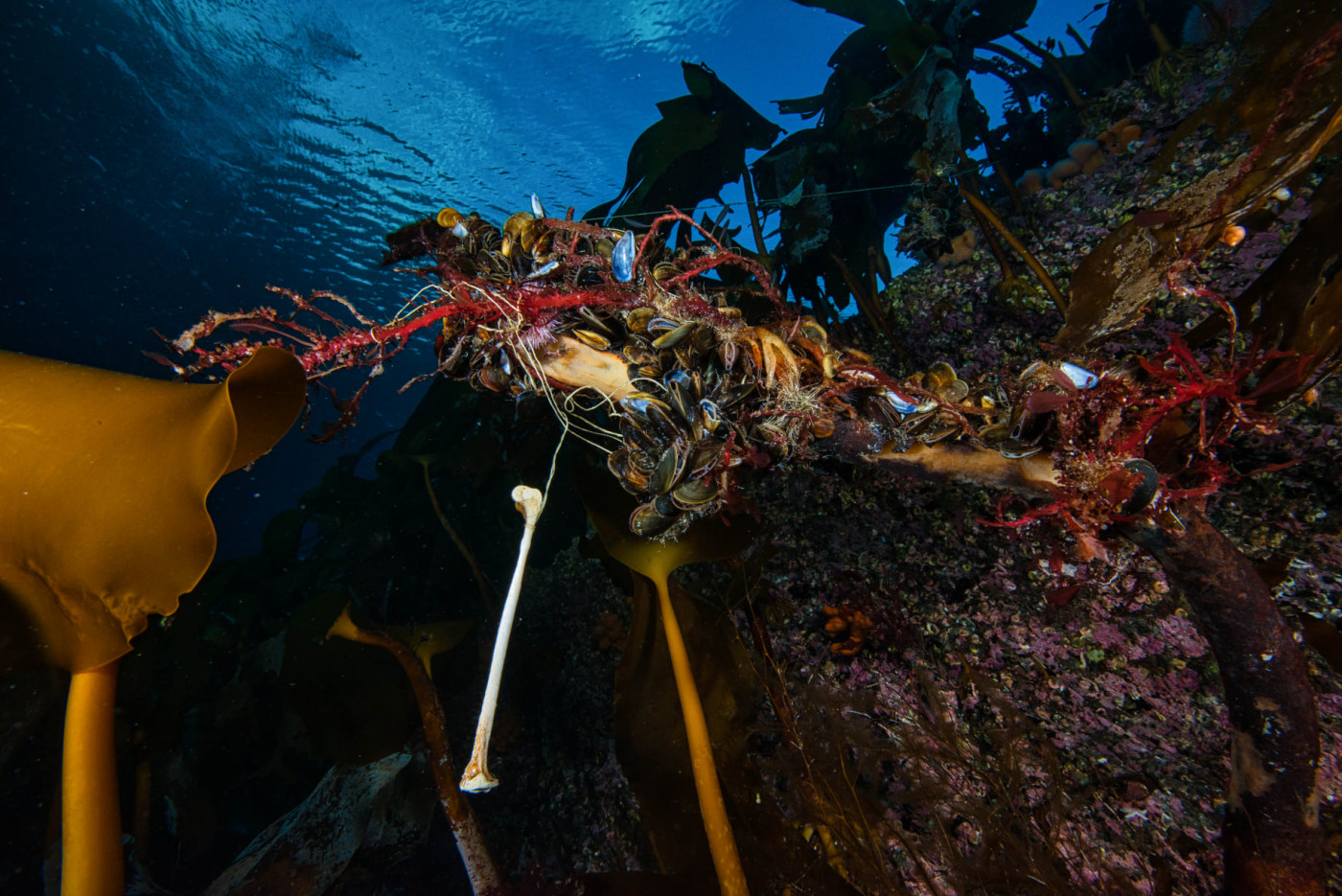

Discarded fishing lines entangled in a kelp forest

Until Borghild and Fredric and Borghild’s ex-husband Vebjørn, who takes most of the photographs they use. In her presentation, Borghild has come to what she calls “the bad pictures.” Kelp forests strewn with fishing lines. A fish trapped by a lost hook and stuck to the sea-bottom, wrapped in and entangled by fishing line. It is a horrible sight. Of course, Borghild freed him, but she thought it was hopeless. “We thought, OK maybe he's dying but we'll give him a last swim and the next day Fredric was diving in the same place and the same fish, with the same scars, came up to him. ‘Look at me! look at me!’”

No permit is required to hunt or fish in this marine protected area. The only thing preventing industrial fishing is the force of the water. But the richness of the underwater world attracts fishers and hunters, and there is nothing to be done about it, even though the establishing law states that “animal life with a connection to the seabed shall be protected from harm and destruction,” and “littering is prohibited.” Under Section 4, exemptions from the protective provisions of section 3, “harvesting of wild marine resources in accordance with the Marine Resources Act, excepting harvesting of vegetation, including seaweed, kelp and other marine plants.” So Borghild and Fredric are right: their beloved wolffish may hang out in caves and on the seabed, they may be benthic, but a kelp plant is more protected than they are.

At Statsforvalteren i Nordland, the regional authority that oversees the MPA, a senior officer tells me that clean-ups are done by professional companies and “local divers,” and that “cleaning up garbage under water in the MPA requires a permit if the cleaning up has a risk of harming conservation values. For example, when it is likely that seaweed plants will be harmed when you remove fishing lines. Otherwise, no permit is needed.”

Borghild is vivacious and cheery, but also gloomy. “More and more people are beginning to discover this paradise underwater. Most come from Denmark but there are also other Europeans. We have to stop this kind of fishing, we have to establish just a few places to fish and the government should pay to clean up the gear every year. But before, the pollution was in just a few areas and now it’s all over.”

Borghild can only hope that her wolffish soap opera makes locals want to protect their MPA as much as she does. As for the fishing tourists, all she can do is “talk, talk, talk”: to the local hotel, to the people who rent fishing boats. “They are trying to make people fish outside the current, not always fish in the current in the protected area. But we want them to say, ‘don’t fish’. Instead, they say, ‘don’t fish more than one or two wolffish inside the current.’” Borghild sounds tired. It is hard work, but it must be done. “Pressure, pressure, just tell people what’s happening. We need to take care of this place. It’s so beautiful and so special.”

Perhaps enough people will be interested in the love life of Pernille and Konrad, or Konrad’s replacement, that they will pay attention to the whole environment of Saltstraumen and perhaps they will sign up to the Facebook group Saltstraumen Marine Protected Area, where Vebjørn and Borghild post episodes of the soap opera alongside gorgeous pictures. As I write this in May 2023, I check out the latest and discover that “all the wolfish fathers in our little valley have now with success finished this season of guarding eggs.” The human guardians are “really looking forward to see the couples in their caves again when midsummer comes,” and meanwhile, “we wish the fathers a well-deserved holiday.”

Trawling and the Threat to Underwater Cultural Heritage

Foresight Review on the Future of Regulatory Systems

Foresight Review of Ocean Safety

Insight report on safety in the fishing industry

Can aquaculture supply chains increase demand for more OSH data?

Revealed: 97% of UK marine protected areas subject to bottom-trawling

Intergovernmental Conference on Marine Biodiversity of Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction