The term “Shipwreck” often prompts thoughts of crashing waves and formidable rocks against which a ship has broken itself to pieces. Britain’s coast is home to the remains of thousands of ships that endured this fate, or something similar. Sites like these are points of fascination. They form dramatic interruptions on beaches and coastal walks and offer windows into a past world.

In 2019 and 2021 the Lloyd’s Register Foundation (LRF) supported the investigation of two shipwreck sites (see Figure 1): the Ocean (Figure 2) on the East Winner Bank, Hampshire, and Rhoda Mary (Figure 3) in the Medway River, Kent. Work on these sites began with the remains of the ships and delved deep into the archive of the LRF’s Heritage and Education Centre (HEC).

The way the ships were approached acknowledged that their influence on the world does not end with their wrecking or discard (Bennett 2010:6). In the 19th century the records compiled by Lloyd’s Register are an example of this. Ships are rated or classed based on the perceived effectiveness of the technologies involved in their construction. They are given a certain number of years for their rating and at a set date they are rated again, provided their annual surveys and maintenance have been satisfactory. This raises the question, to what extent are those ratings influenced by technologies that have been effective before and what is the effect of something new and different?

It is important to recognise that ships can be considered as both individual artefacts and assemblages of multiple artefacts. Those “assemblages” include traditional (in an archaeological sense) material “things” and ideas that went into their creation, documents, people involved, and forces acting upon ships (Jervis 2019: 37). “Assemblage Archaeology” (Lucas 2012; Jervis 2019) when combined with the awareness of “process” advocated by Gosden and Malafouris (2015), recognizes the role of these components whether human, non-human, conceptual, or physical. Those components may not all play a single role, some may be material and functional, whilst others could be expressive (Hamilakis and Jones 2017: 79). Materiality, this study of things, is a process of forming connections and relations, those relationships are what matter (Lucas 2012: 167-8). This awareness of relationship between components of a ship is central to understanding the two sites investigated.

Impact Review 2022

Shipwreck Sites of Ocean and Rhoda Mary

Wreck of the merchant schooner Ocean

The hulk of the merchant schooner Rhoda Mary

Impact Review 2022

Shipwreck Sites of Ocean and Rhoda Mary

Wreck of the merchant schooner Ocean

The hulk of the merchant schooner Rhoda Mary

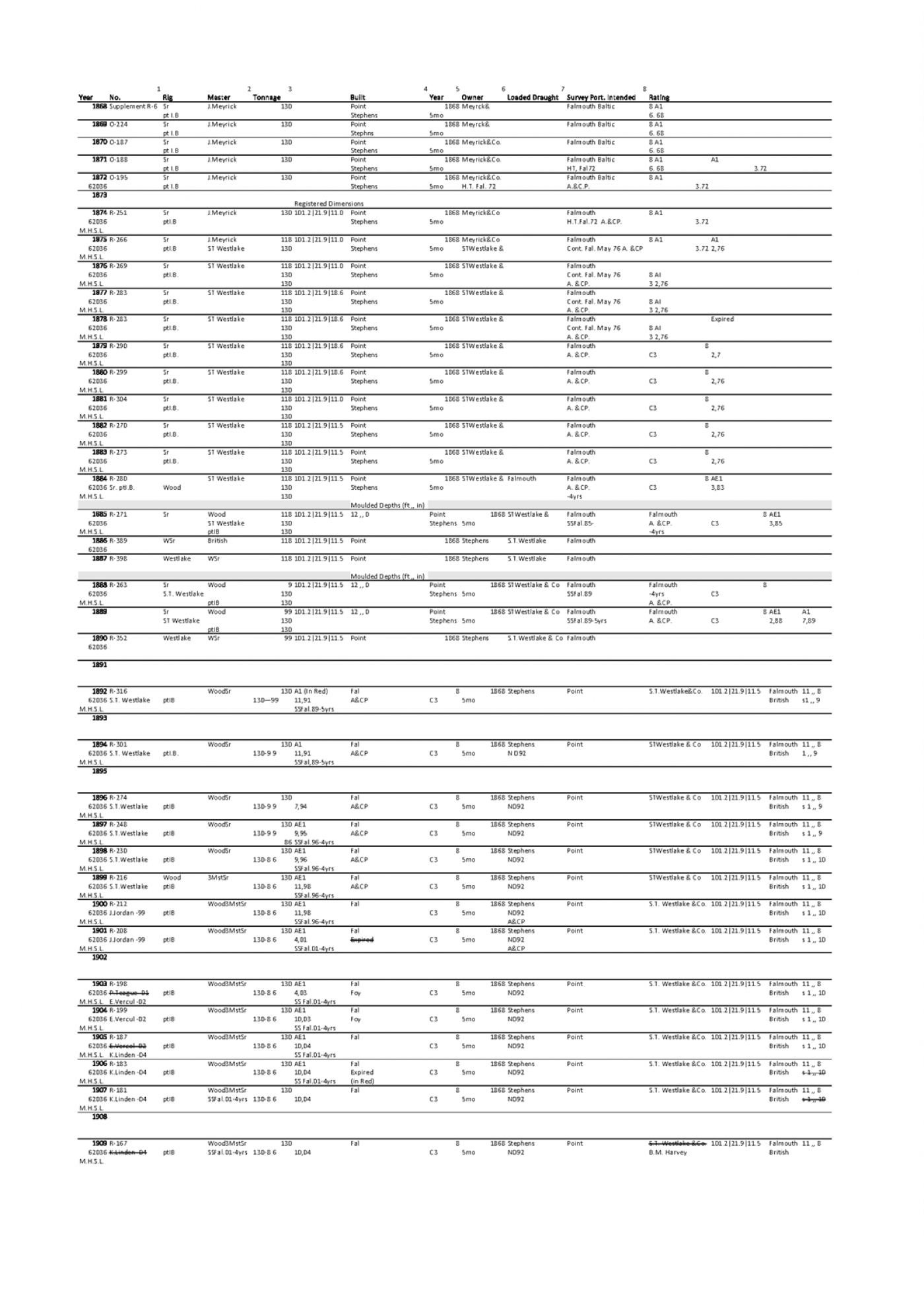

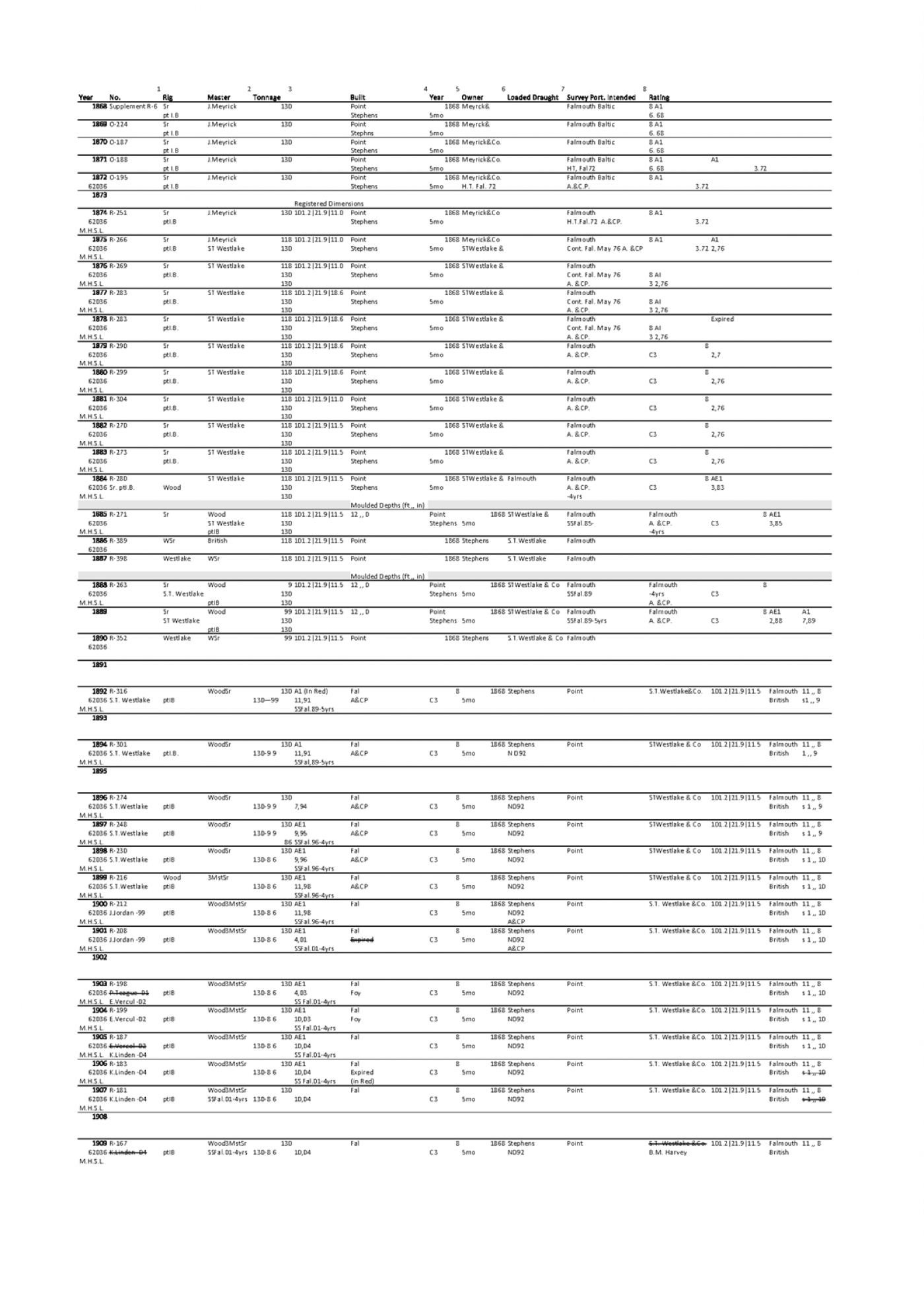

The resources within the HEC’s archive provide a depth and granularity that allows archaeologists to ‘see’ the past maritime world ships operated in. For example, the Lloyd’s Register of Ships (LRS) illuminates different milestones in a ship’s life, such as the destined voyage at time of publication, repair events, changes in ownership, and more. The entries from the LRS can be used to construct a lifeway table for each ship (e.g., Table 1). These records allow archaeologists to engage directly with the everyday life of a ship, and reach the people associated with it who otherwise may not appear anywhere in the historical record. Their inclusion returns a distinctly human element to the study of the bits of wood and metal that make up a ship (Dolwick 2008: 25 and 2009: 21-22). The investigation of those sites can then explore beyond the immediate area of the wreck itself and into the role of ships in past systems of trade or communication.

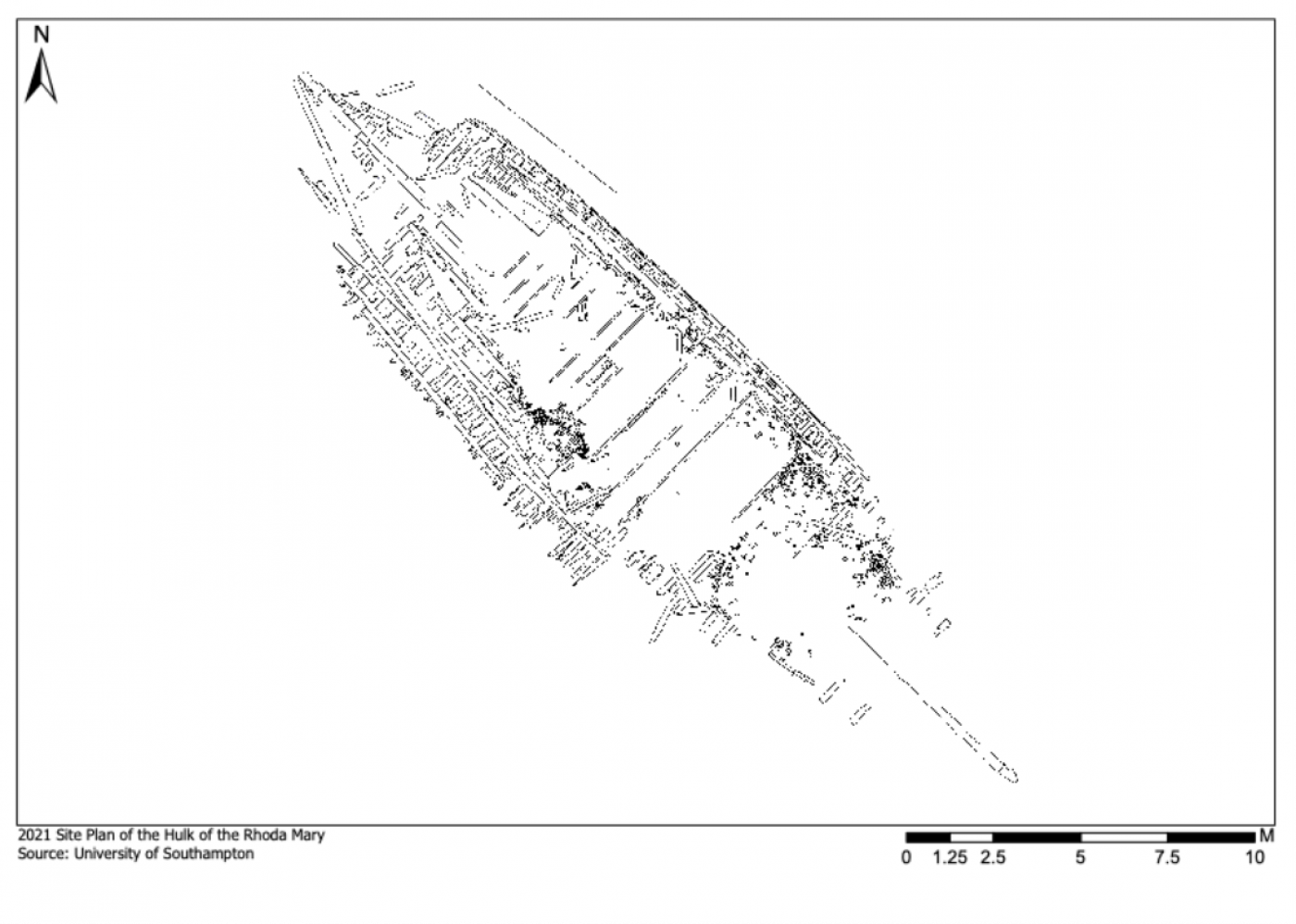

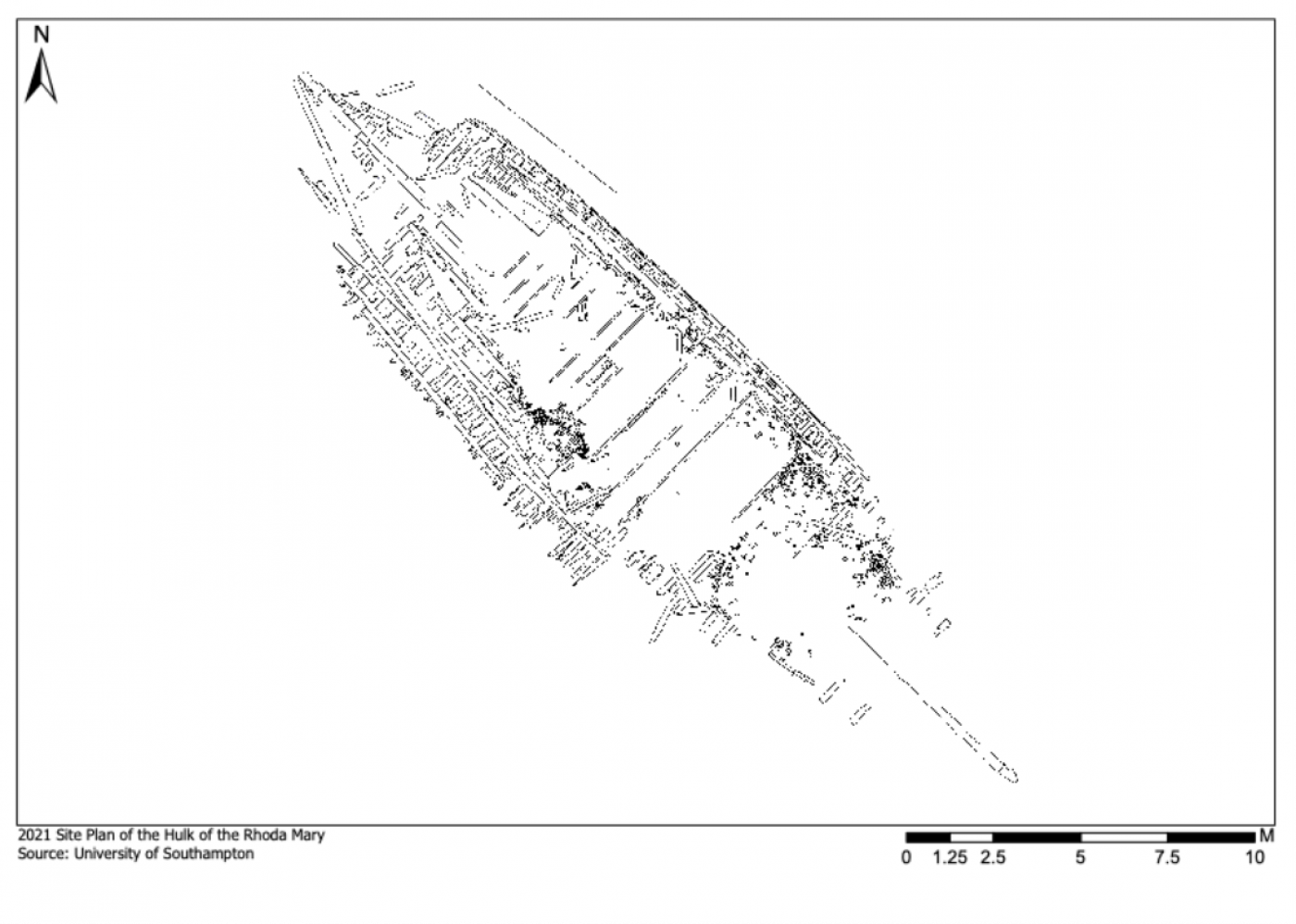

Work on sites like these cannot be undertaken alone. So, a team of archaeologists, from the University of Southampton’s Centre for Maritime Archaeology (CMA) deployed to explore each site. For Ocean in particular teamwork was essential because the site is only exposed for 40 minutes at extreme tides. We used tools that facilitated rapid study of the site to collect as much information as possible, including drone photography (Figure 3), ultra-high precision GPS systems, and photogrammetry. In other words, we generated a lot of data about the ships, from their size and location, plans of their shipwrecks (such as that for Rhoda Mary in Figure 4), to the technologies used in their construction.

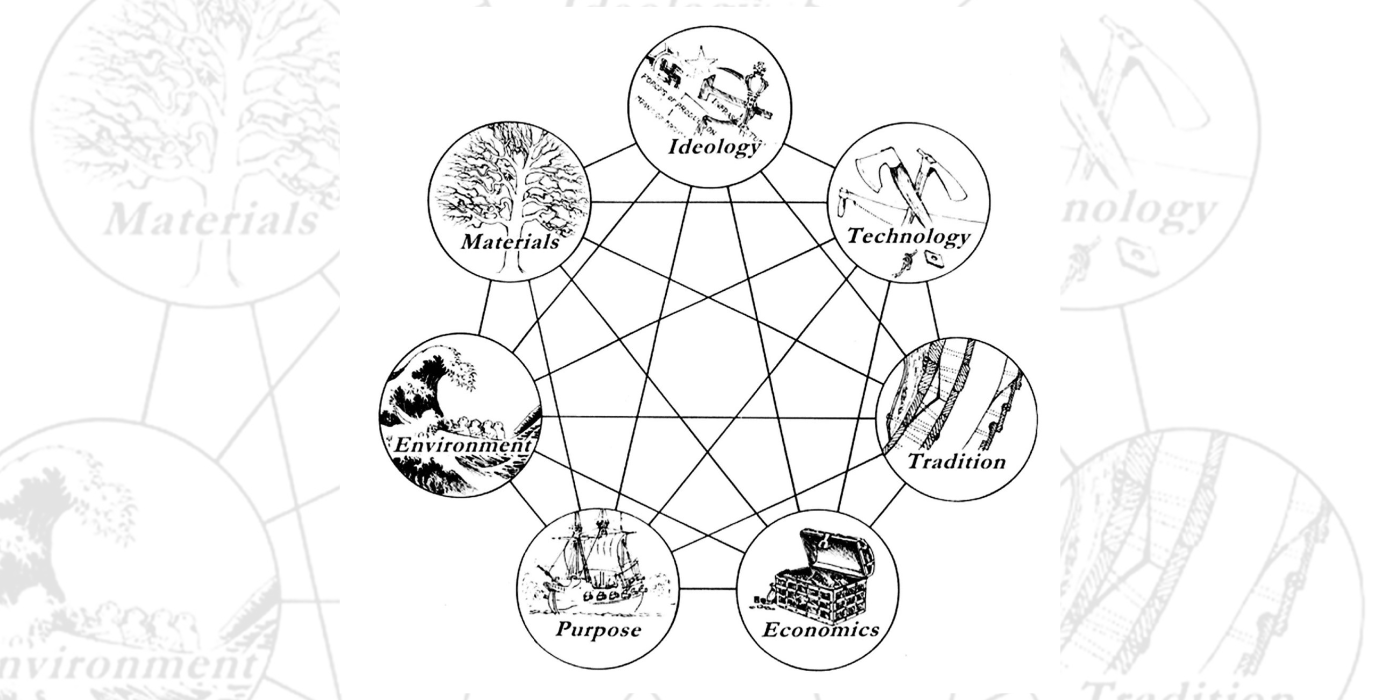

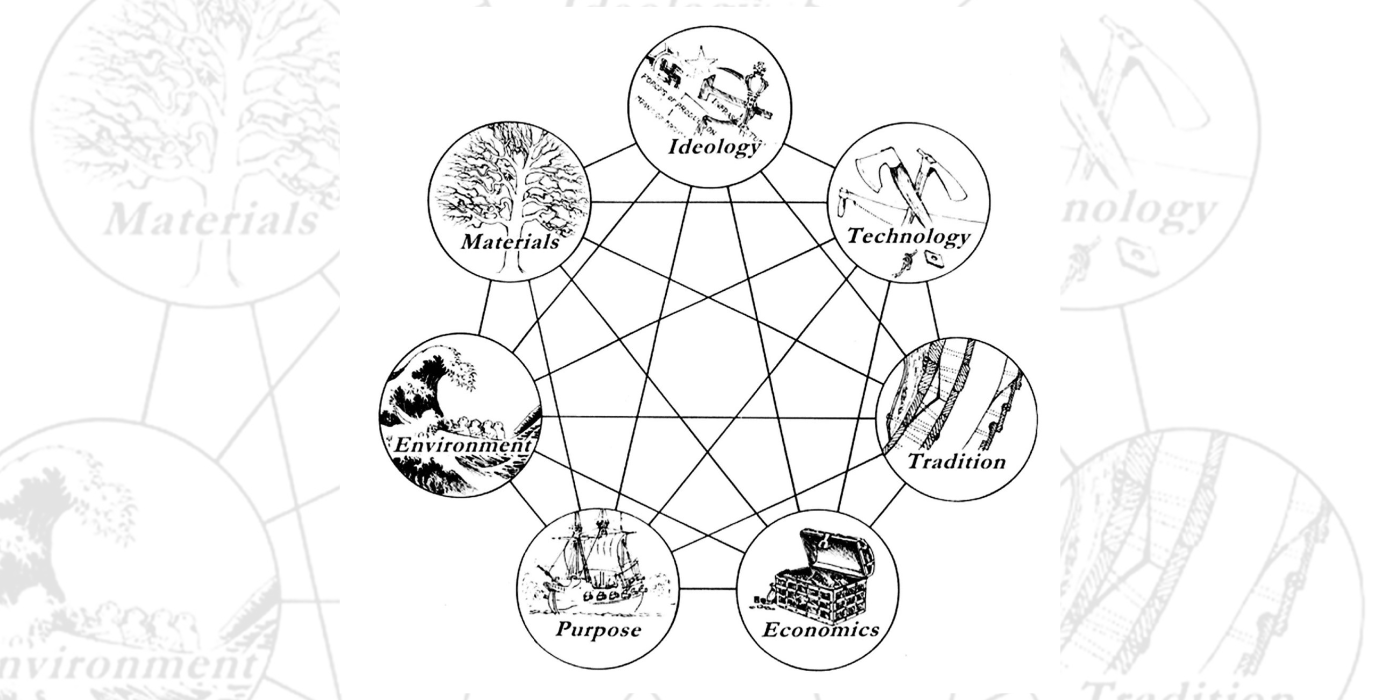

As archaeologists we know that specific components within shipwreck sites can illuminate a ship’s story, and specifically tell us where and when it was built and what choices were made in that process (e.g., Adams et al. 1990: 124-30; Ossowski 2008: 37; Whitewright and Satchell: 2011: 43-9; also see Olaberria 2018 for an excellent discussion on approaches to ship design). Combining this with the detail in the HEC’s archive unpicks even more about a ship’s story. From the key components identified in the archaeological investigation of a shipwreck (Figure 5) we can trace the life of a ship through the HEC records and specifically the LRS.

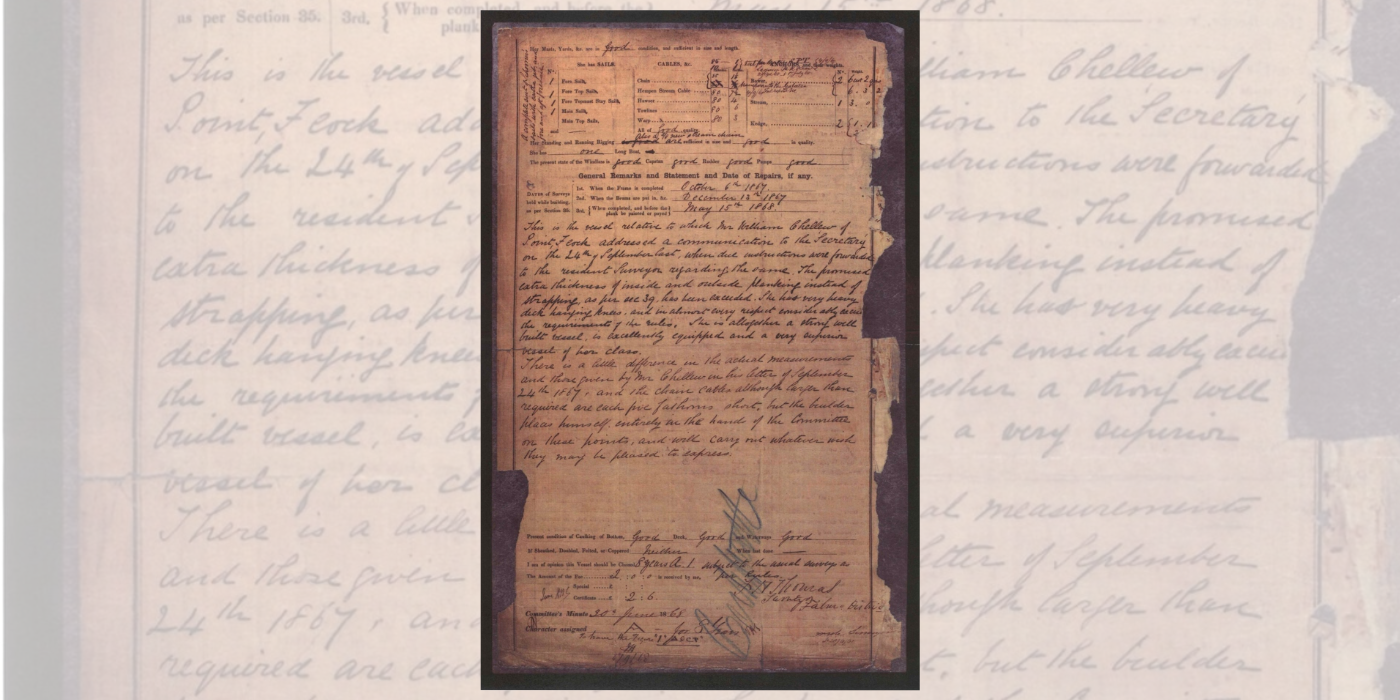

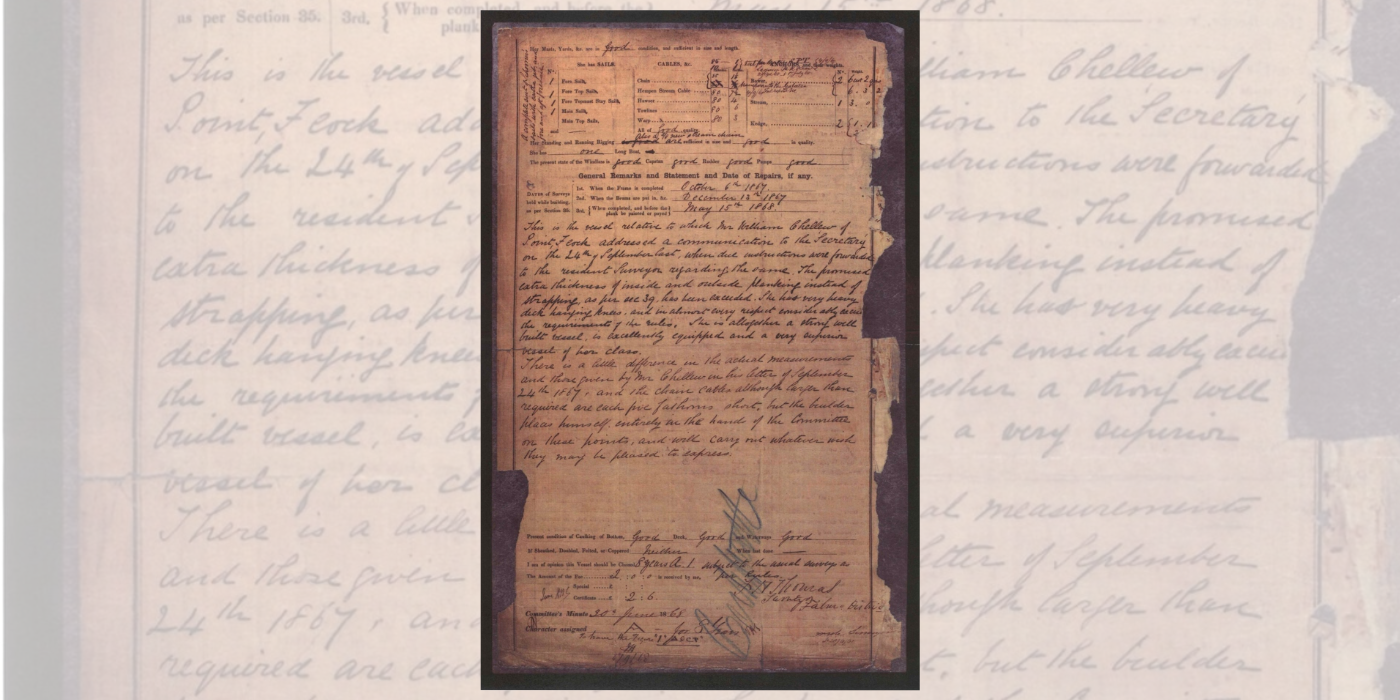

The choices being made when building a ship can be explored in much more detail by including material beyond the shipwreck site (Figure 7 and Adams 2001: 301 and 2013: 47-9). Further records from the HEC add more information, principally the ship survey reports conducted by the Lloyd’s Register (LR) surveyors. These allow unparalleled access into the process of shipbuilding and even the specific approaches of individual shipbuilders. The Survey Report for Rhoda Mary contains a fascinating account of correspondence between the shipbuilder and the LR General Committee, which authorised the ship’s classification and the record for that ship in the Register (Figure 8). These showed that the shipbuilder was actively pursuing the best rating possible from the LR surveyor ensuring the construction of his ship met or exceeded all Lloyd’s Register’s Rules for the Classification of Ships in use at the time. This shows that not only is the LRS an historic record, but it also acts as an active influence on processes and people. The LRS and the processes behind it are playing a meaningful role in decision-making.

A drone recording the shipwreck of Ocean

The lifeway table for Rhoda Mary

Archaeological site plan of the hulk of Rhoda Mary

Different factors that influence how watercraft come into existence

Rhoda Mary Survey Report

A drone recording the shipwreck of Ocean

The lifeway table for Rhoda Mary

Archaeological site plan of the hulk of Rhoda Mary

Different factors that influence how watercraft come into existence

Rhoda Mary Survey Report

Archives like the one held by the HEC enable archaeologists to undertake investigations that have not been possible before. This is primarily due to the HEC’s digitisation project which unlocked the potential of the Lloyd’s Register’s archive. The accessibility of the archive and the depth its material offers makes it an essential component in archaeological investigations of shipwrecks dating from the 19th century to the present. The work undertaken in these projects revealed stories of two shipwrecks, discussing everyday seafaring and merchant ships that formed the foundation of the global trade powering an Empire. These stories and the people within them would otherwise remain untold and may not appear in other investigations of the past or the maritime world.

Explore the Lloyd's Register Foundation Impact Review 2022, 'Together'.

Downloads