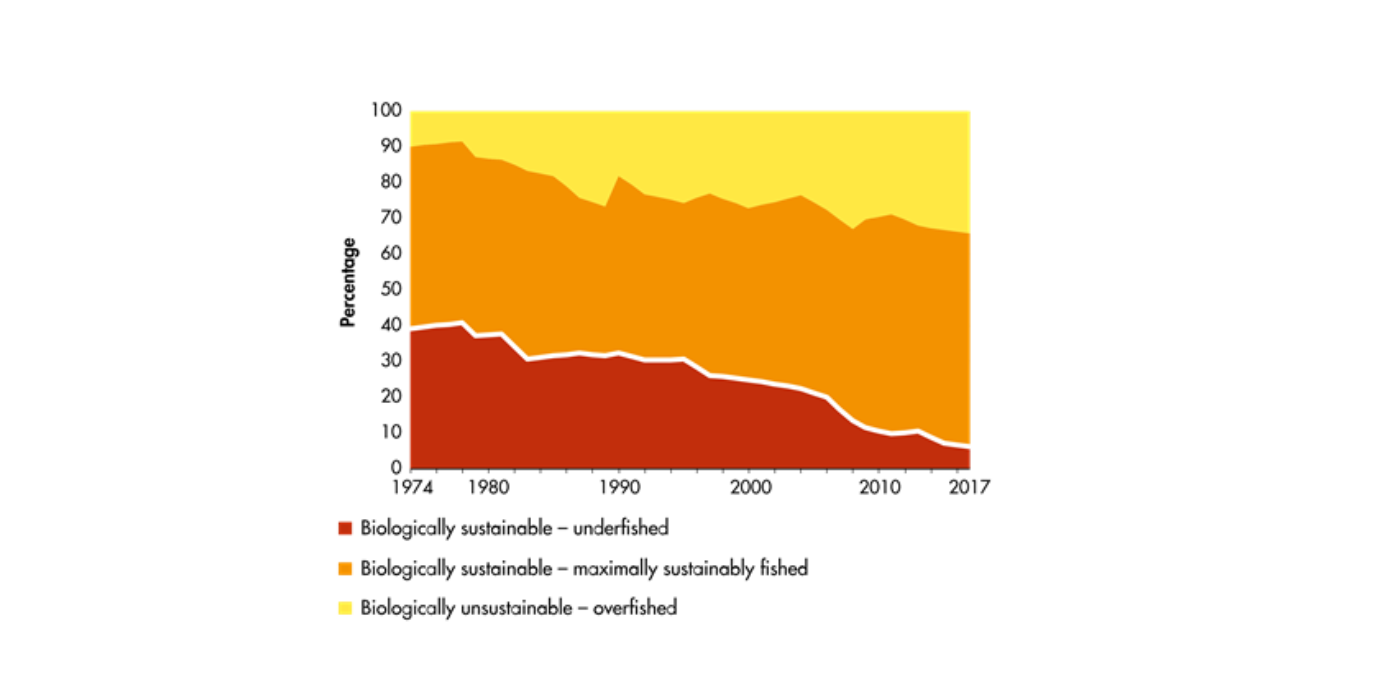

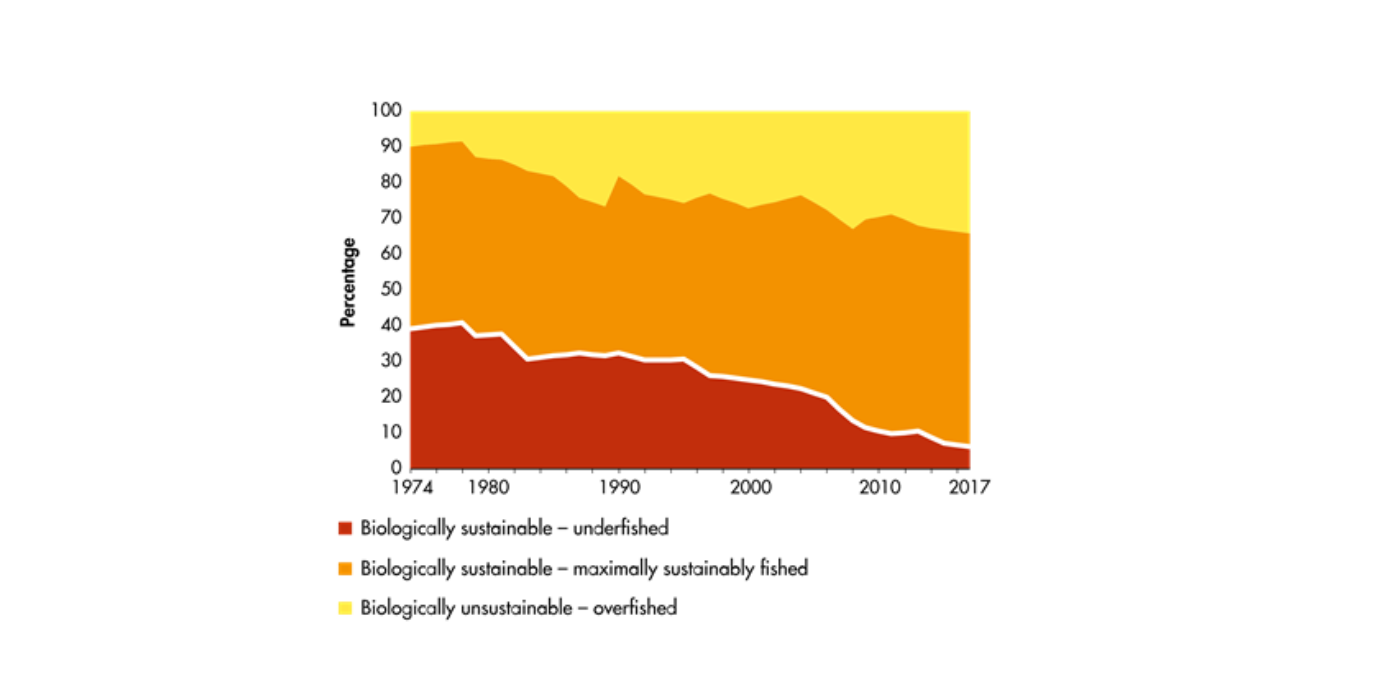

Overfishing occurs when more fish are removed from the ecosystem than can naturally replace themselves. For thousands of years, people have fished sustainably; with their level of technology, they could never catch anything approaching close to the replacement rate of the stock. That changed with the expansion and modernisation of fishing to become the commercial fishing industry. Enormous trawlers, better techniques for finding shoals, and nets miles long that catch many tonnes of fish at a time are the new, terrifying reality. According to the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), as of 2022, nearly a third of all monitored global fish stocks are overfished, and over 60% are fished to the maximum sustainable yield. 1

Global trends in the state of the world's marine fish stocks

Close-up cages used to contain farmed fish

Global trends in the state of the world's marine fish stocks

Close-up cages used to contain farmed fish

This unbridled exploitation leads to severe consequences, which we have already seen historically in the 1970s with the collapse of the herring fishery off the coast of Europe.

In the 1960s, the herring fishing around Europe was booming. New technology enabled more powerful boats to easily locate shoals. Furthermore, fishing was a free-for-all in open waters 12 miles from each country’s coastline. 2 As a result, in the 1970s, the fish population crashed drastically.

A total ban on herring fishing came into place in 1977, followed by a moratorium where only very limited quotas were permitted. All countries around the North Sea enforced this in their own waters, which they extended from 12 to 200 miles. Communities which had built their lives around the herring, such as the east coast of Scotland, Norway, the Netherlands, and Iceland, were devastated economically. For example, the Dutch fleet went from 50 herring trawlers to only 12 when the ban was lifted in 1983. 3 They had to adapt to new catches, such as mackerel or langoustines. It took 20 years for herring stocks to recover, and even now, they still have not reached the same heights as in the 1960s, if they ever will.

Much has been learned from the herring collapse of the 1970s. It takes a long time for fish numbers to recover, if they ever do, so prevention is much better than cure. There are now attempts to manage fisheries sustainably all over the world. This is done by both governments on a national and international level, through Marine Protected Areas (MPA) and non-profit organisations such as the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC). So, what is being done?

As previously mentioned, after the herring collapse, governments extended their maritime borders into exclusive economic zones of 200 miles from their shoreline, allowing them complete control of resources within those zones. This is codified in the third United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. 4 This, however, has potential to lead to conflicts and clashes of interest between governments, as seen when the United Kingdom (UK) and Iceland clashed over cod after Iceland set up an exclusive economic zone, barring UK vessels from fishing there. This also does not solve enforcement in true international waters, allowing continued exploitation of fish stocks there.

Fishing quotas, or total allowable catches (TACs) are another government-enforced method for managing fishing stocks sustainably. They specify how many tonnes of a certain species can be landed each year, and what the minimum size the fish needs to be to avoid targeting juveniles that have not yet had time to breed and replenish the stock. This is usually based on the results of scientific monitoring by organisations, such as the Scientific, Technical and Economic Committee for Fisheries, which sets the quotas for the EU.

However, these quotas only specify what can be landed, so any fish that is over quota or bycatch is discarded as waste, which is costly and does not solve the original problem.

It is also rarely popular with fishing communities, as they are- at best- limited in their economic growth, or- at worst- pushed out by corporations who snatch up the quotas. Furthermore, it relies on the science and monitoring being accurate, which is not always the case. This was felt strongly by Newfoundland in 1992, when the cod fishery collapsed due to overestimation of available cod stocks. 5 The local community was devastated, and the cod still has not recovered.

Bycatch from a shrimper in Belgium

Close-up cages used to contain farmed fish

Bycatch from a shrimper in Belgium

Close-up cages used to contain farmed fish

Government efforts have been significant, but non-profit organisations have also been hard at work. The Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) is a well-known non-profit which monitors fisheries and sets standards to which fisheries are independently certified as sustainable with a blue label check. 6 Any fish sold from these fisheries carries this mark, which combined with consumer awareness, pushes up demand. This works well for the fishing community too, as these higher prices incentivise them to continue their practices. Yet the certification is hard to achieve and limited in scope. With only 7% of world fisheries certified 7, there is a long way to go.

Farmed seafood takes pressure off wild stocks in theory by raising fish and other animals in captivity, allowing greater management. It has become a popular practice, with 49% of the seafood we eat coming from aquaculture. 8 Fish farming, however, can have environmental impacts without proper management. Forcing out wildlife from their natural habitat, pollution, and illnesses spreading from farmed fish to wild populations can all decimate fish stocks as much, if not more, than unsustainable fishing practices.

Sustainable fishing is a complex problem that requires multiple solutions and work across governments, organisations, and communities to properly work. The consequences of failing to do so are devastating, ravaging communities and ecosystems, and requiring even more extreme measures such as moratoriums and bans to work. We can all do a little to help prevent this fate by choosing to eat fish from sustainable fisheries certified by the MSC, or farmed fish with high welfare standards, and avoiding seafood whose origins are questionable.

With climate change and pollution placing additional burdens on fish, sustainability is a vital goal to work towards for preserving biodiversity, keeping the world fed, and communities with an income.

Dickey-Collas, Mark, et al. “Lessons Learned from Stock Collapse and Recovery of North Sea Herring: A Review” ICES Journal of Marine Science, vol. 67, no. 9, 2010, pp. 1875–1886.

FAO. “The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2022. Towards Blue Transformation” Rome, FAO, 2022.

European Commission, “Fishing Quotas”, https://oceans-andfisheries.ec.europa.eu/fisheries/rules/fishing-quotas_en

Gordon, Daniel V., and Rögnvaldur Hannesson. “The Norwegian Winter Herring Fishery: A Story of Technological Progress and Stock Collapse.” Land Economics, vol. 91, no. 2, 2015, pp. 362–85.

Hannesson, Rögnvaldur. “Stock Crash and Recovery: The Norwegian Spring Spawning Herring.” Economic Analysis and Policy, vol. 74, 2022, pp. 45–58

Hannesson, Rögnvaldur, et al. “The Collapse of the Norwegian Herring Fisheries in the 1960s and 1970s: Crisis, Adaptation and Recovery.” in Climate Change and the Economics of the World’s Fisheries: Examples of Small Pelagic Stocks, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, UK, 2006, pp. 33–65.

International Institute for Law of the Sea Studies, www.iilss.net

Marine Stewardship Council, www.msc.org

Myers, Ransom A., et al. “Why Do Fish Stocks Collapse? The Example of Cod in Atlantic Canada.” Ecological Applications, vol. 7, no. 1, 1997, pp. 91–106.

WWF, www.wwf.org.uk

Footnotes

-

1

FAO, “The Status of Fishery Resources.” www.fao.org/3/cc0461en/online/sofia/2022/status-of-fishery-resources.html

-

2

Hannesson, Rögnvaldur. “Stock Crash and Recovery: The Norwegian Spring Spawning Herring.” Economic Analysis and Policy, vol. 74, 2022, pp. 45–58

-

3

Dickey-Collas, Mark, et al. “Lessons Learned from Stock Collapse and Recovery of North Sea Herring: A Review.” ICES Journal of Marine Science, vol. 67, no. 9, 2010, pp. 1875–1886

-

4

International Institute for Law of the Sea Studies, “Exclusive Fishery Zones Meaning and Which Countries Have It?” IILSS, 13 Jan. 2023, iilss.net/exclusive-fishery-zones-meaning-and-which-countries-have-it/

-

5

Myers, Ransom A., et al. “Why Do Fish Stocks Collapse? The Example of Cod in Atlantic Canada.” Ecological Applications, vol. 7, no. 1, 1997, pp. 91–106

-

6

The MSC became very widely known following the release of Seaspiracy on Netflix in March 2021. Their response to this can be found here

-

7

WWF, “Making Fishing Sustainable.” wwf.panda.org/wwf_news/?199902%2FMaking-fishing-sustainable. Accessed 18 June 2023

-

8

FAO, “Global Fisheries and Aquaculture at a Glance.” Global fisheries and aquaculture at a glance (fao.org)