Royal Leith

On 15th August 1822 George IV stepped ashore at the port of Leith to roaring crowds, the first royal visit to Scotland since 1650. Living under a mile away on Portland Terrace was 33 year-old Leith-born ship’s master, Walter Paton. He would later serve as Lloyd’s Register’s Surveyor for Leith and the Firth of Forth for 29 years; his letters and reports reveal life in one of Britain’s biggest and bustling ports.

Early Life

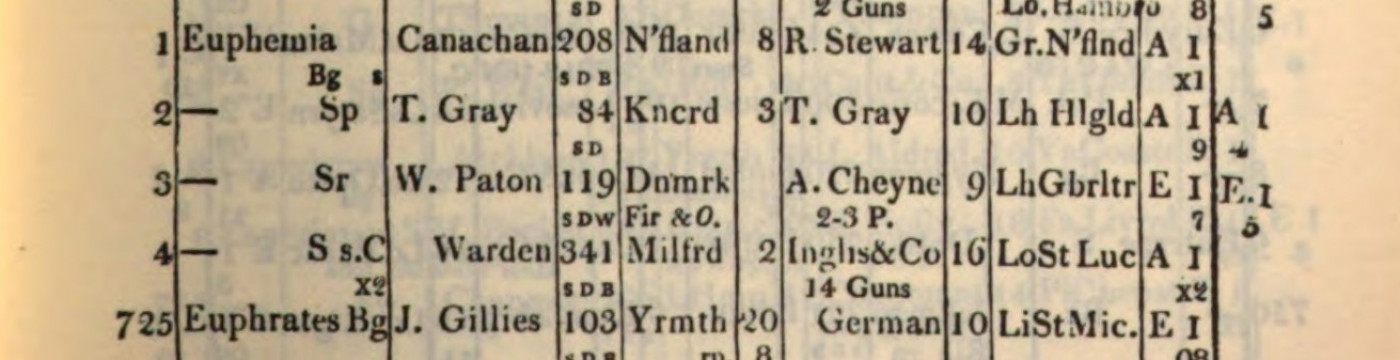

Walter Paton was born 2nd February 1789, to Ann Bell and Thomas Paton, a local ropemaker. The eldest of five, his early life remains unknown, though his father died when he was 11. Growing up not far from the docks that served the city of Edinburgh, Paton quickly ran away to sea. In 1813, a record of the 119-ton schooner Euphemia appears in the Register Book showing Paton as the ship’s master on a voyage between Leith and Gibraltar. He would go on to master three more ships that took him across Europe.

Becoming a Surveyor

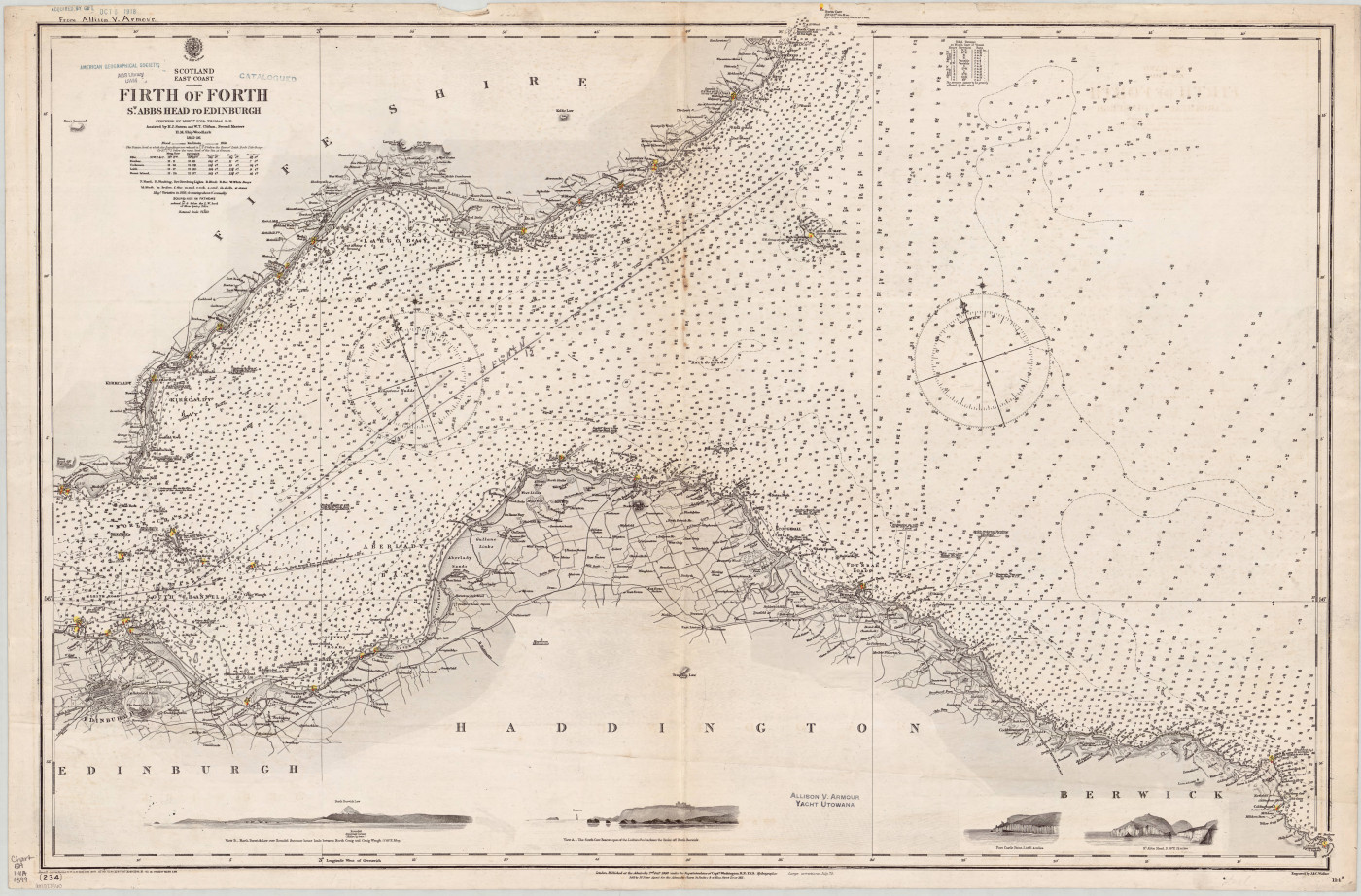

In 1834, 63 trusted surveyors were recruited across the UK. Of these, 13 were exclusive appointments to key ports; places like London, Bristol, Newcastle, Clyde, and Leith. These were men of sound practical experience, with backgrounds in shipyards or as ship’s masters, with proven skills in ship construction, and crucially, the trust to carry out their work in small, sometimes isolated communities. Paton was appointed Surveyor for Leith and the ports of the Firth of Forth. However, records show that he operated continuously between Berwick-upon-Tweed and Fife, as well as the ports of the Firth of Forth- over 120 miles!

Life in Leith

Upon Paton’s appointment at Leith, the population numbered roughly 27,000; nearly a third of which were engaged in shipping. A once great major port, Leith now struggled with two issues: chronic debt, and stiff competition from the Clyde. The City of Edinburgh declared bankruptcy in 1833; Leith became a fully independent burgh. To stave off bankruptcy, shipping bore the brunt, with heavy duties imposed on anchorage, flaggage, and pilotage- all before HM Customs had taken their cut. Subsequently, Aberdeen, Dundee, and Glasgow benefited. Maintaining a strong trade in materials like coal and timber, Leith also boasted success in fishing, and whaling.

Early Surveys

Carrying out his first survey on 10th May 1834, Walter Paton found himself inspecting the 1804 Chester built brig Diligence, bound for St. Petersburg. It’s precious cargo? Cheese.

As an officer of Lloyd’s Register, Paton was a familiar trusted face in the region. His letter books give a running account of all aspects of his work. In 1842, he complained of Leith’s harbourmaster, whose ‘bad language’ and ‘difficult behaviour’ made him a poor ambassador for the port.

In the case of surveying the schooner Allison, in June 1840, Paton records that the vessel had been built with timbers from another vessel wrecked 20 miles away. It had been at sea for just 15 hours!

Engines, Boilers, and Steam

Possessing a keen eye for risk, Paton was an early proponent of the need for greater regulation over machinery aboard ships, particularly boilers:

Leith, 18th March 1839

‘I inspected one of the steamers and found her to be a strong and substantial vessel. On inquiry I was informed they have occasional surveys on the engines and boilers…; but, in my opinion it is not such a survey as ought to be deemed sufficient, being made by the engineer and boiler maker, who do the work for this company, and, of course, not so impartial or independent as neutral persons may supposed to be.’

It was not until 1873 that engines, boilers and machinery would be considered a compulsory part of the survey.

At Work

Paton’s work made him a useful ally for shipbuilders and owners, though his letters also reveal that for the less scrupulous, surveyors posed a risk to business, with an emphasis on rules and high standards. On 9th June 1845 he wrote to the Chairman at London:

‘We have been using every exertion to trace out the writer of the anonymous letters and have offered a reward of fifty guineas to any one who will bring forward such proof as will lead to his conviction, in my mind I have now scarcely a doubt as to the individual.’

A Representative

Paton also advocated for local shipbuilders and owners. In October 1847, Paton intervened in the case of the newly constructed barque Marli, built by local shipwright, John Duncanson. Built on a contract, the ship required minor alteration to achieve the class needed to satisfy the buyer. The Society insisted alterations must be carried out before the class was awarded. Paton, bringing the Surveyor at Liverpool, and the Surveyor at Aberdeen to Alloa for their opinion, wrote a letter on Duncanson’s behalf, which included a character reference. Duncanson constructed ‘good sound ships’ and always had them surveyed. Sadly, he was at real risk of losing his shipyard; his wife, brother, foreman, and eldest son had all died within weeks of each other, leaving him alone with three small children. Receiving, three letters from different surveyors, the Society awarded the classification for free, provided that repairs were effected after the next voyage.

Last Survey

From 1862 onwards, Paton was increasingly assisted by fellow surveyors. The surveyor at Liverpool wrote that Paton was frequently fatigued by ‘long journeys and poor weather.’

In April 1863, Walter Paton carried out his last official survey on the Glasgow built iron screw steamer Triennial.

At the end of nearly 30 years, he had surveyed over 1200 ships and drafted 3114 reports and filling three archive boxes. Having trained the young Benjamin Martell as the Surveyor at Leith, his signature disappears. That was not however, the end of his story…

Retirement in Leith

A final letter from Walter Paton, dated 19th September 1864, responding to a request for his notes. He reports that he had only recently received the request, as he had been on holiday on the West Coast. After declaring that he had deposited all his letters, personal papers, and other ephemera with the office at London (which we retain to this day), he signed off.

Paton died in 1873 at age 84, whilst visiting his daughter at Greenock. Leith had changed dramatically since his birth; in terms of shipbuilding, owning and registering, the port had lost out to the great pioneering yards of the Clyde.

Yet, Paton left a legacy there. Serving as Master of Trinity House, Leith, 1856-1868, he sat for an oil painting, aged 73. It still hangs at Trinity House today, a reminder of his long service and commitment to ensuring safety at sea in his home port.