Thursday, February 15 2018

One of the highlights of my job working with Project Undaunted is that I never know what I will find from one day to the next. The collection held by the Lloyd's Register Foundation (LRF) comprises survey reports, plans and correspondence that relate to specific ships that were surveyed between 1834 and the late 1960s. It is the most extensive collection of its kind with potential for ground breaking maritime study and research. These reports relate the condition, damage repairs, construction and modifications of the ships, as recorded by the Lloyd's Register (LR) surveyors during the course of their inspections. Project Undaunted aims to catalogue and digitise this vast collection with a view to making it accessible to the public.

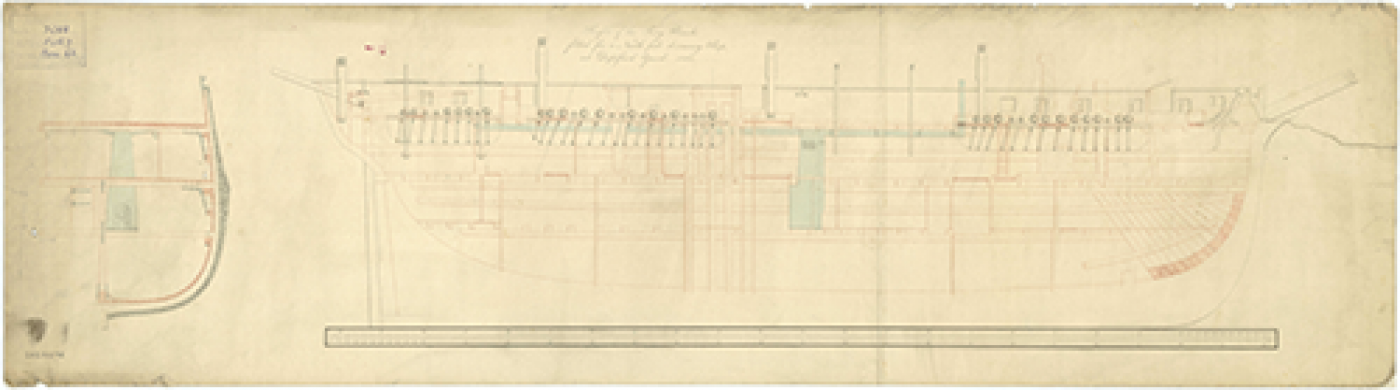

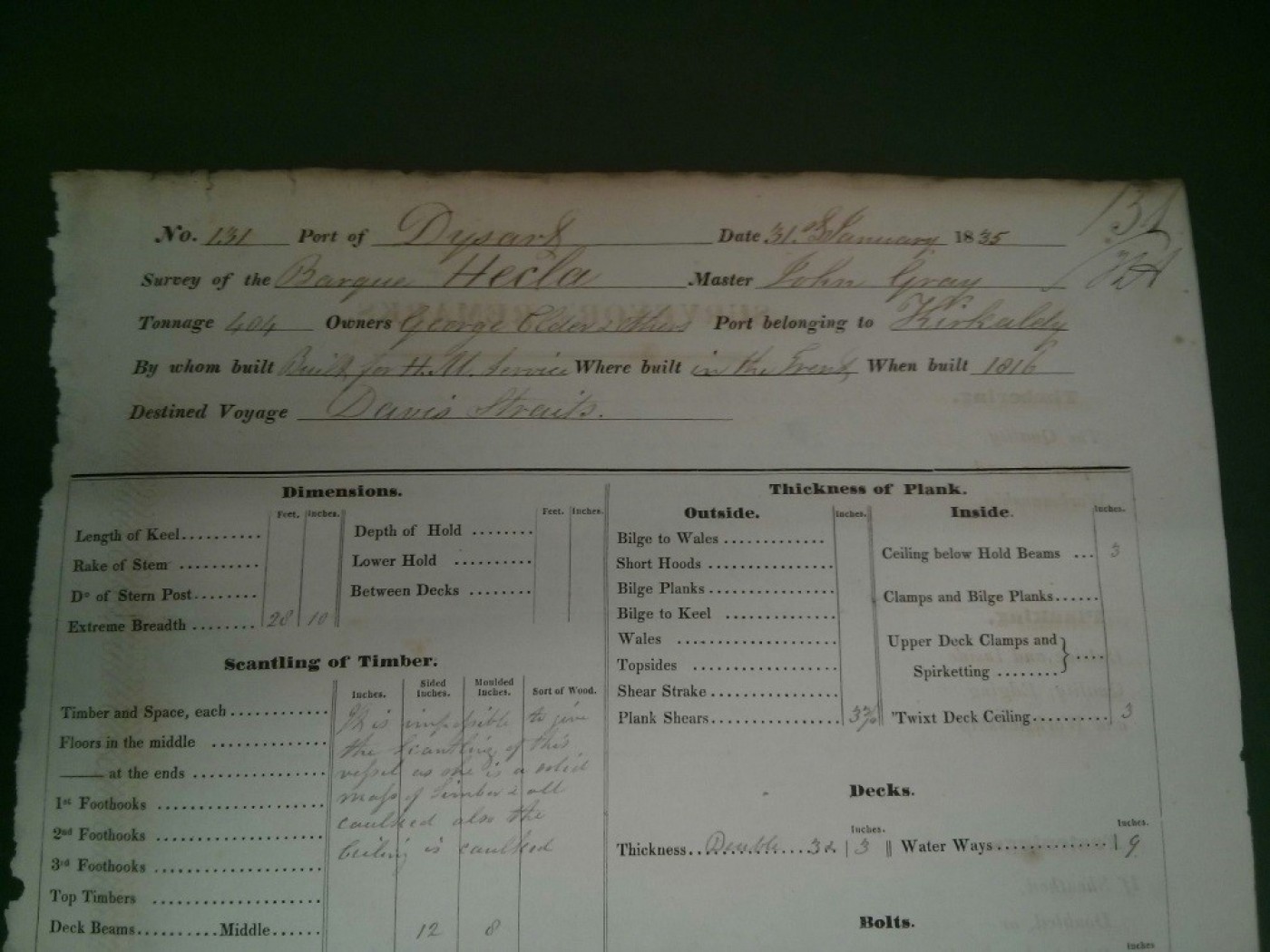

For quite some time I have been cataloguing the earliest LRF records for the port of Leith. As the principal port for the city of Edinburgh and the southeast of Scotland, it has been fascinating to document the shipping history of Leith through the eyes of Lloyd's Register's long serving surveyor, Walter Paton. It was on one of these days digging through a mass of correspondence and survey reports that I came across an entry for a particularly remarkable ship. When Paton visited this ship at Dysart in 1835 he wrote ‘This is without exception the strongest I have met with.’1 Paton found he was surveying one of the most well-known and celebrated vessels of her time. Famous throughout the world for her voyages of discovery to the Arctic in search of the fabled Northwest Passage; she had been sold into private hands and slipped into anonymity, her fate unknown. This article recounts the complete story of the ship Hecla, better known as HMS (His Majesty’s Ship) Hecla.

Third Voyage to the Arctic 1824-1825

When Hecla returned to Britain in 1823 her exploits had captured the attention of the British public and her reputation was firmly established. Prior to her departure on 8 May 1824 over six thousand people visited her at Deptford as she was fitted out for her next voyage.[1] Once again she was to seek out the fabled Northwest Passage, this time entering Lancaster Sound and turning south to explore any gaps in the coastline of Prince Regent Inlet. This time Parry chose to return in Hecla with Commander Henry Parkyns Hoppner in Fury. Having been a lieutenant on both Griper and Hecla, Hoppner’s Arctic service record and skills as a draughtsman made him the perfect choice for a command in Parry’s third voyage. After a rousing concert and dance attended by over three hundred on the decks of Hecla, the two ships bid farewell and departed once again for the Arctic.[2]

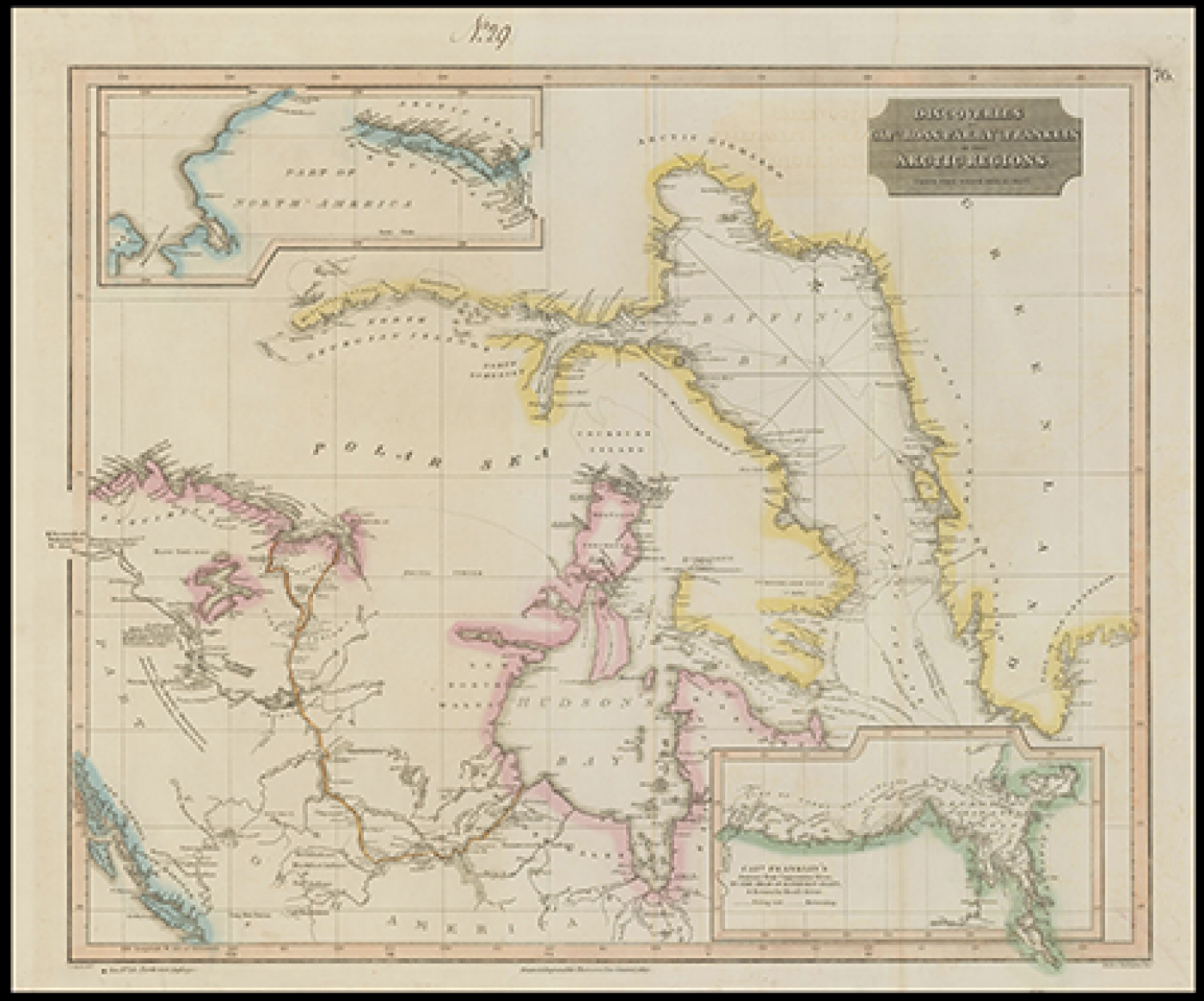

One month after leaving England ice was spotted, an unexpected and regrettable sight. Not long after, Hecla’s quartermaster descended below decks as Parry gave Sunday service, to inform him that land had been spotted dead ahead. Finishing his sermon Parry was able to narrowly avert disaster before turning his attention to reaching Prince Regent Inlet before winter. Nonetheless 1824 was to prove colder than anticipated, the ice lingered and for the next two months the two ships struggled to break through Baffin Bay. Reaching Prince Regent Inlet a little while later, hopes of open waters to the south were shattered as they met impenetrable ice. Unwilling to push on through the ice and risk becoming trapped, Hecla and Fury were forced to turn back as far as the entrance of Lancaster Sound and set up winter quarters at Port Bowen. Once these quarters were secured Parry turned his attention to keeping the men busy. ‘Every attention was, as usual, paid to the occupation and diversion of the men’s minds, as well as to the regularity of their bodily exercise.'[3] One such entertainment was a suggestion from Commander Hoppner; a masquerade ball, with the crew dressed as Turks, Quakers, chimney sweeps, rag-and-bone men and Parry playing the part of a one legged marine begging for halfpennies, it proved a roaring success and was continued every month.[4] Beer was also brewed on board Fury and a tavern created below her decks named ‘The Fury, No 1 Arctic Street’ to which sailors purchased tickets. As well as providing entertainment for the crew the expedition also yielded significant scientific research over the nine months spent at Port Bowen. Parry oversaw the work of Lieutenant’s Ross and Foster as they studied gravity, geomagnetism, astronomy and the meteor showers that occurred throughout December.[5] Efforts were also made to capture and preserve the variety of Arctic fauna that they came across. With the coming of spring in 1825 two sledge expeditions were launched to scour the coastline to the north and south.

On 20 July 1825, Hecla and Fury departed Port Bowen. Heading towards the entrance of Prince Regent Inlet, the two ships crept along North Somerset and eagerly gazed out in search of a passage along the coastline and four hundred foot high cliffs. Despite hopes of a passage through North Somerset’s sheer cliff coastline, great icebergs still restricted the movement of the two ships. Rather than turn back out of Prince Regent Inlet and abandon the expedition Parry decided to push on, navigating between the shallow beaches at the base of the cliffs and the shifting ice floes. This proved to be a decisive mistake, and the fortunes of the expedition took a turn for the worse with the rising of the wind.

Parry recorded: ‘This wind, which was always troublesome to us, soon brought the ice closer and closer, till it pressed with very considerable violence on both ships, though the most upon the Fury, which lay in a very exposed position.'[6] Not long after, as they continued south, both ships were thrown onto the beach unable to move. As Hecla began to move off from the beach with the rising of the tide Parry received word from Hoppner that the Fury had been severely “nipped” and had begun to leak at a rate of four inches an hour.[7] In steering away from the ice floes that began to encroach on their path Hoppner had struck the low-lying beach hard. Though the crew took to the pumps non-stop for forty-eight hours it rapidly became clear that the ship’s fate rested on hauling her up, examining her hull and making any necessary repairs as quickly as possible. The two ship’s companies attempted to prepare an ice dock to expose her bottom but this was quickly destroyed by the fierce winds. With a makeshift repair carried out using her sails Hecla was tasked with towing Fury to a safer inlet further along the coast. For four days Hecla navigated a slow laborious passage through the ice before Fury was purposefully beached by Hoppner for examination and her supplies removed and placed on the shore. Within minutes Parry, Hoppner and the officers quickly came to the conclusion that Fury was beyond repair. Stacking her supplies, anchors, boats and provisions on the beach, Parry gave the order for the men of Fury to collect their belongings and prepare their sleeping arrangements on board Hecla. With Hecla now accommodating the two ships’ companies and supplies running low, Parry took the decision to abandon the expedition. ‘I was, therefore reduced to the only remaining conclusion, that it was my duty, under all the circumstances of the case, to return to England…'[8] Leaving Furybehind on what became known as ‘Fury Beach’, those supplies left on the shore were to be of vital use to the survival of Sir John Ross’ expedition (1829-1833). Though the fate of the Northwest Passage was still undecided, by the time they arrived back at Peterhead in October 1825, Hecla had successfully battled her way home without a single loss of life. This was to be the last time that Parry was to make an attempt for the Northwest Passage.

Voyage to the North Pole, 1827

When Parry returned from his third voyage he did not anticipate a return to the Arctic, and became a hydrographer for the Navy, settling down with his wife Isabella not long after. Since Franklin’s expedition of 1818 many championed the prospect of a voyage to the North Pole across the frozen Arctic Sea. In 1826 Sir John Barrow privately sent Parry a copy of Franklin’s proposition urging him to put his name forward. Much to his delight Parry was eager for a break in hydrography and once again began drawing up a proposal to the Admiralty. With Royal Society backing, Parry proposed a trip by boat and sledge across the Arctic Sea to the North Pole with a fully planned scientific programme. By July 1826 Parry’s plan of action was approved by the Admiralty and he was left with instructions to pick his ship’s company, and prepare Hecla once again for the Arctic. To give the expedition an even greater incentive Parliament also pledged a £1000 reward to any British subject that reached 83˚ north.

With instructions to hoist a flag at the North Pole stitched by his wife, Parry weighed Hecla’s anchor and left Deptford on 26 March 1827. Not long after they departed the ship’s company sustained a casualty near Northfleet on the River Thames; the seaman John Gordon. Gordon had tragically become caught in chain cable and dragged to the bottom of the river while laying an anchor that threatened to turn over one of Hecla’s boats. The expedition held a service to Gordon before continuing out of the Thames estuary and into the North Sea, putting in at Hammerfest, Norway a few weeks later. There Parry purchased the reindeer that were to carry the sledges over the ice and oversaw the training of the crew for walking on skis and making camp in the snow. After purchasing any final provisions for the trek across the ice Hecla left Hammerfest and sailed north, arriving at Spitzbergen (Svalbard) on 21 May. Fierce winds and fast moving glaciers trapped Hecla amongst the ice floes and impressed upon Parry the need to secure a safe harbour for the ship. It was to be twenty four days before the ship was freed from the ice.[9] Cutting through the ice and heavily delayed Heclasuccessfully moored at Treurenburg Bay in mid-June as Parry readied the two boat sledges.

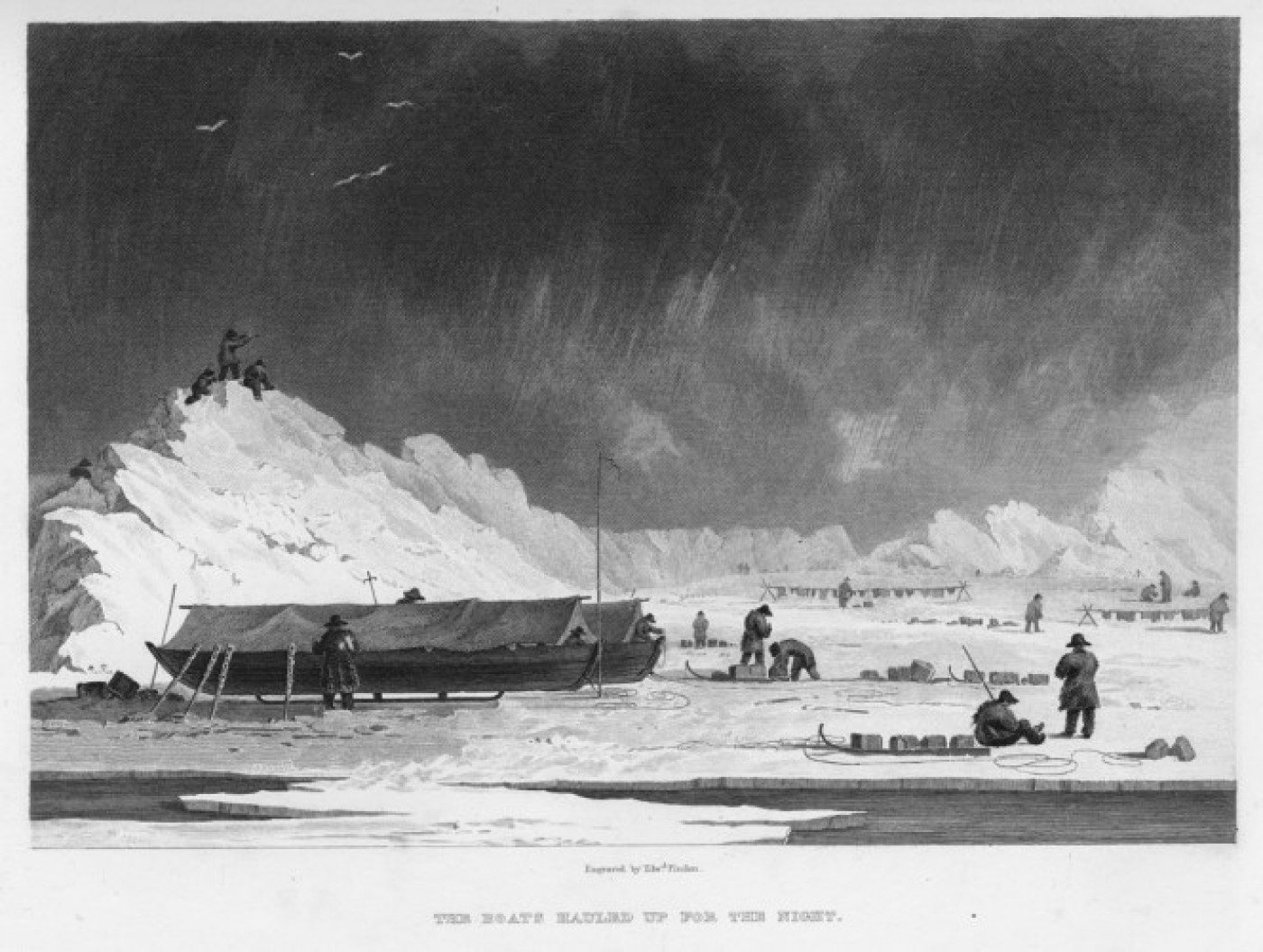

Two boat sledges each 20 feet long had been specially crafted for use on the journey to be pulled by both reindeer and men, fashioned out of oak and Norwegian fir and to seat up to 14 with room for supplies.[10] Duly named Enterprise and Endeavour Parry set out with the two boat sledges, leaving Hecla under the command of Lieutenant Foster and confirming a rendezvous point with her on Walden Island. Reaching the ice sheet on 21 June Parry and his men ventured out in search of the North Pole. Over the next two and a half months the sledge crews travelled by night struggling through snow blindness, uneven terrain and against the shifting of the ice sheet drifting ever southwards away from their purpose. On 27 July at their encampment Parry calculated their position to be 82˚ north, twenty miles from their destination and the £1000 reward. Suffering from fatigue and dwindling supplies the sledges had travelled a total of 580 miles and were 172 miles from Hecla in the depths of the Arctic wilderness.[11] To the disappointment of Parry and his men the search for the North Pole was abandoned. Hoisting the ensign at 82˚ north, the crew made one final toast to the health of the king, to Mrs Parry, and to his father-in-law Sir John Stanley before they began the long trek back to the rendezvous point. By the time they finally reached the coast and returned to Hecla on 21 August, Parry was informed that she had run aground, been refloated and subsequently beached to protect her from the ice floes. A short while later Hecla set a course for Britain, reaching Peterhead in October.

Parry disembarked from Hecla, leaving her under the command of Ross as he hurried back to London for an appointment and debrief at the Admiralty. To his surprise the Admiralty congratulated him on his performance and for breaking the furthest north record; a record that was to remain his for the next forty nine years. As Hecla made her way to Deptford, Ross prepared her for a final visit from the Lord High Admiral, the Duke of Clarence, later William IV, before she was paid off and officially taken out of Arctic service on 1 November. Heclawas to be Parry’s last command at sea and he was never to return to the Arctic again. By the time of his death in 1855 Parry’s reputation as a British hero was firmly established; the most southerly and northerly points of the globe still bear his name to this day.[12] Parry had decisively made his mark in the history and geography of the world, and what’s more, he had done so in His Majesty’s Ship Hecla.

Shortly after Hecla’s triumphant return up the River Thames, it was decided that she was to put out to sea for the purposes of science and exploration, this time on a far smaller scale. In December 1827 she was placed under the command of Captain Thomas Boteler and tasked with surveying the western coast of Africa. In this venture Captain Boteler and a large portion of the ship’s company perished toward the end of 1829 after an outbreak of yellow fever. Commander F Harding succeeded Boteler. Despite this, between 1827 and 1831 Hecla was again performing valuable work in cartography and contributing to a greater understanding of the African continent. With a successful job completed the Admiralty recalled Hecla to England in 1831 for the last time.

At the ripe age of 15 years old HMS Hecla was formally decommissioned and sold in April 1831 for £1,990, just shy of £100,000 in modern money. The naval historian E C Coleman writes that by the time of her sale she was the most experienced polar explorer in the world.[13]

After the Navy

Here the known naval records for Hecla end. However, just as her naval service drew to a close, she was granted a new lease of life with the beginning of a varied but little known chapter, her merchant career. Unlike many of her sister ships Hecla was to keep her name throughout her commercial life, a testament to her fame and reputation and a source of pride to her owners. Purchased by Sir Edward Banks, the famous builder of London, Southwark and Waterloo bridges, she was sold not long after to an Aberdeen based trader, Thomas Bannerman for one season. It is here in 1832 that she first appears in the Lloyd’s Register of Ships, captained by an R Jumson with an LR classification of E1. The surveyors at Lloyd's Register would have inspected these ships and completed their reports with a recommendation for class which was deliberated formally by a Committee of Classification. The first character refers to the condition of the hull, ranging from 'A', 'AE', 'E' or 'I', and the second figure of class denotes the condition of her equipment, either '1' or '2'. Once awarded a class with the society, each vessel became eligible for entry into the Lloyd’s Register of Ships, an annually updated alphabetical list of every ship surveyed by LR. The Registercontains information relating to the owner, master, tonnage, place of build, date of build, port of registry, voyages, and most importantly their class. With a class of E1, Hecla had seen better days. Her first entry in the Register also shows that she was travelling to St Petersburg and Savannah, Georgia in 1832 and 1833 respectively.[14] Records then show that she was sold in 1834 to a professional whaling outfit by the name of George Elder & Co, registered to the port of Kirkcaldy and captained initially by a W Ellis and then a John Gray. On 31 January 1835, not long after George Elder had purchased Hecla, she put in at Dysart for a survey afloat by the Lloyd’s Register Surveyor for Leith, Walter Paton. It was here in conversation with Gray that he recorded in Leith survey report No 131 that the vessel had been converted for the purposes of whaling three years earlier. Under the section entitled 'Remarks' Paton confirms the identity of this ship, 'she was built originally for a bomb, but afterwards fitted out for Captn. Parry's Northern expedition.' Without this single affirmation I, or any other individual, may never have recognised the importance of this document in identifying Hecla. However, what is particularly noteworthy is that she was undergoing repair for a voyage to the Canadian Arctic Circle, specifically the Davis Strait. Though it is commonly believed that Hecla never ventured to the Arctic after her sale, the Lloyd’s Register of Ships proves that she was to return every year. Ironically Hecla was to hunt in the exact area she had opened up to whaling and explored in 1819. Her last record appears in the Lloyd’s Register of Ships for 1840. The previous year her classification reads ‘wants repairs’; perhaps indicating that damage had been sustained on her trips to and from the Arctic. The final record for Hecla in the Register indicates that her last voyage was to the Davis Straits and that she was wrecked in 1840. Basil Lubbock in The Arctic Whalers records that she was ‘lost in ice’ that year...[15]

Though Hecla’s ultimate fate may never be known in entirety her legacy lives on in the annals of history and is forever etched into the Arctic; Hecla and Griper Bay, the Hecla and Fury Strait, and Hecla Cove to name only a few. The exploits of ships like Hecla were closely followed by millions across the globe and came to epitomise the spirit of enterprise, daring and fortitude that were to characterise British exploration. In short, these ships changed the world. Though Hecla’s life has been documented thoroughly since her voyages of discovery it is her life post-Navy that has proved elusive. Her tonnage had changed significantly from those of the naval records, her date of build was mistakenly recorded as 1816 instead of 1815, and the restrictions of printing space only afforded her place of build to be listed as the River Trent in the Register Book. Though these may have given clues to identifying her, it is only with the survey report, the diligence of the surveyor, Walter Paton in recording this vital piece of information, and through the work of Project Undaunted that her identity could have been confirmed.

The Project Undaunted team have worked tirelessly to catalogue and examine LR’s expansive collection of survey reports and correspondence. It is hoped that through the work of Project Undaunted LR will inspire academic and social interest in this wide-ranging collection; the oldest and largest of its kind. Working as a part of this project and with such a varied and extensive collection, it is a joy to be able to contribute to the rediscovery of ships like HMS Hecla and to the study of maritime history. In the coming days and weeks I look forward to the next discovery that Project Undaunted will yield. At this stage we have only begun to scratch the surface.

- [1] Ships of Discovery and Exploration, Lincoln P Paine, pg. 78

- [2] The Royal Navy in Polar Exploration from Frobisher to Ross, E C Coleman, pg. 245

- [3] Journal of a Third Voyager for the Discovery of a North-West Passage from the Atlantic to the Pacific, Captain William Edward Parry, pg. 62

- [4] The Royal Navy in Polar Exploration from Frobisher to Ross, E C Coleman, pg. 247

- [5] The Royal Navy in Polar Exploration from Frobisher to Ross, E C Coleman, pg. 247

- [6] Journal of a Third Voyager for the Discovery of a North-West Passage from the Atlantic to the Pacific, Captain William Edward Parry, pg. 104

- [7] Journal of a Third Voyager for the Discovery of a North-West Passage from the Atlantic to the Pacific, Captain William Edward Parry, pg. 106

- [8] Journal of a Third Voyager for the Discovery of a North-West Passage from the Atlantic to the Pacific, Captain William Edward Parry, pg. 131

- [9] The Royal Navy in Polar Exploration from Frobisher to Ross, E C Coleman, pg. 289

- [10] The Royal Navy in Polar Exploration from Frobisher to Ross, E C Coleman, pg. 289

- [11] The Royal Navy in Polar Exploration from Frobisher to Ross, E C Coleman, pg. 292

- [12] The Royal Navy in Polar Exploration from Frobisher to Ross, E C Coleman, pg. 294

- [13] The Royal Navy in Polar Exploration from Frobisher to Ross, E C Coleman, pg. 294

- [14] Lloyd's Register of Ships, 1832

- [15] Lloyd's Register of British and Foreign Shipping from 1st July 1840 to 30th June 1841