Thursday, February 08 2018

One of the highlights of my job working with Project Undaunted is that I never know what I will find from one day to the next. The collection held by the Lloyd's Register Foundation (LRF) comprises survey reports, plans and correspondence that relate to specific ships that were surveyed between 1834 and the late 1960s. It is the most extensive collection of its kind with potential for ground breaking maritime study and research. These reports relate the condition, damage repairs, construction and modifications of the ships, as recorded by the Lloyd's Register (LR) surveyors during the course of their inspections. Project Undaunted aims to catalogue and digitise this vast collection with a view to making it accessible to the public.

For quite some time I have been cataloguing the earliest LRF records for the port of Leith. As the principal port for the city of Edinburgh and the southeast of Scotland, it has been fascinating to document the shipping history of Leith through the eyes of Lloyd's Register's long serving surveyor, Walter Paton. It was on one of these days digging through a mass of correspondence and survey reports that I came across an entry for a particularly remarkable ship. When Paton visited this ship at Dysart in 1835 he wrote ‘This is without exception the strongest I have met with.’1 Paton found he was surveying one of the most well-known and celebrated vessels of her time. Famous throughout the world for her voyages of discovery to the Arctic in search of the fabled Northwest Passage; she had been sold into private hands and slipped into anonymity, her fate unknown. This article recounts the complete story of the ship Hecla, better known as HMS (His Majesty’s Ship) Hecla.

Second Voyage to the Arctic 1821-1823

In the final days of 1820, Secretary of the Admiralty, John Barrow informed Parry that he was to return to the Arctic Circle in search of the Northwest Passage. The next voyage would take a more southerly route. This time Barrow took inspiration from Christopher Middleton’s voyage of 1742 and presented Parry with orders to pass through Hudson’s Bay, into Fox’s Basin, and westwards through Repulse Bay where Middleton had been forced to turn back.[1] From there he would follow the coastline and attempt to reach North America via the Behring’s Strait. Hecla was commissioned for exploration under Commander George Francis Lyon and was once again to be serving alongside her sister vessel HMS Fury, commanded by Parry. Lyon had been chosen for his reputation and bravery in exploring the Sahara desert as well as for his proven ability as a sketch artist; his sketches of the Arctic epitomising the voyage.

Following the successful conclusion of the first voyage, Parry was showered with honours and decorations, as befitting an ‘Explorer of the Polar Seas’. Hailed as a British hero, he was made a fellow of the Royal Society in February 1821, given the freedom of the cities of Bath and Norwich, along with a box made from the wood of Hecla, and invited with his friend and fellow commander, George Francis Lyon, to a private audience with King George IV. Upon being told that Lyon would accompany Parry on his return voyage, the king replied ‘Yes, and to share in his honours.'[2]

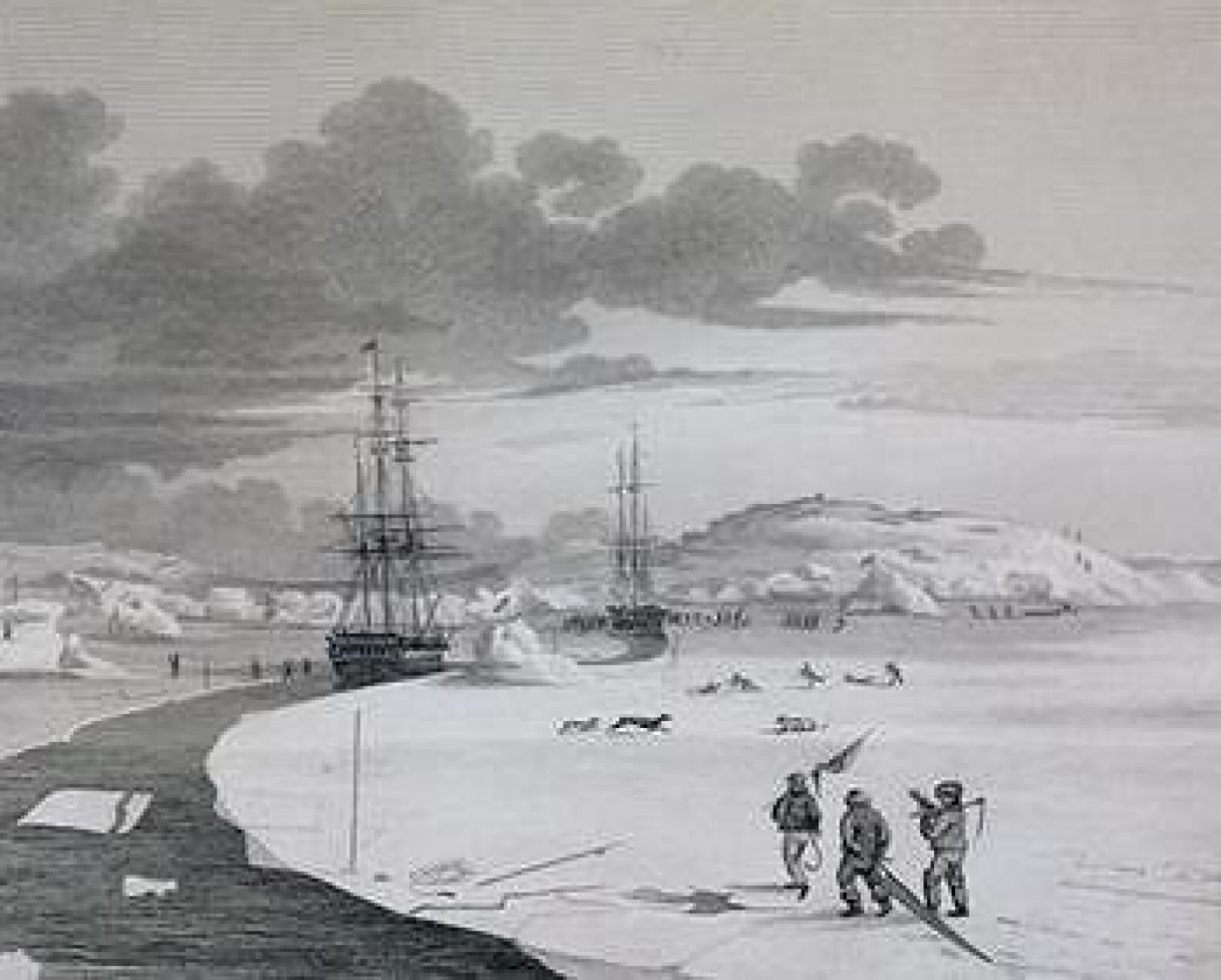

Fitted out with supplies to last three years, Hecla and Fury left London for the Arctic on 29 April 1821.[3] The two ships crossed the Atlantic without problem alongside the supply vessel Nautilus before transferring the stores at the mouth of the Davis Strait. Progress through the ice was slower than expected through Hudson’s Bay, but one month later the two ships reached the northerly tip of Southampton Island. Eighty one years earlier Captain Middleton had forced his way through the Frozen Strait and into Repulse Bay where thick impenetrable ice forced him to abandon the expedition and return to England. For many years debate raged on as to whether a route to the west lay through this bay and with this in mind Parry ventured in. For three weeks the two ships crept forward through dense fog behind the boats and leadsmen as they piloted a safe course between the ice floes.[4] On 22 August with visibility improving, Hecla’s Lieutenant Palmer reported that the passage terminated into a cove. ‘Thus was the question settled as to the continuity of land round Repulse Bay, and the doubts and conjectures, which had so long been entertained respecting it, set at rest forever.'[5]

After declaring that Repulse Bay offered no hope of a path to the Pacific Parry chose to head north, clinging to the coast of the Melville Peninsula and mapping his findings. After discounting an inlet and naming it after Commander Lyon, winter approached faster than anticipated and Parry took the decision to put in at Winter Island and quarter there for the season. Under Parry’s superintendence both crews quickly made arrangements to secure the ships as had been done the previous year, as were routine health checks. It was not long before the decision was taken to officially open the Royal Arctic Theatre, with a performance fortnightly on the decks of Fury. In addition Parry opened the Arctic Orchestra, headed by him on the violin. A school was also established between the hours of six and eight o’clock for the purposes of teaching illiterate seamen to read. By the end of this voyage it is believed that every man was successfully taught to read and write and Parry observed; ‘I have seldom experienced feelings of higher gratification than in this rare and interesting sight.'[6] An observatory was also established, the skeletons of polar creatures were preserved for the Royal Society, and several species of Arctic birds and foxes were captured as specimens for scientific classification. Months later in February 1822, Parry and Lyon were alerted that a group of ‘strange people’ were fast approaching the ships from out of the wilderness.

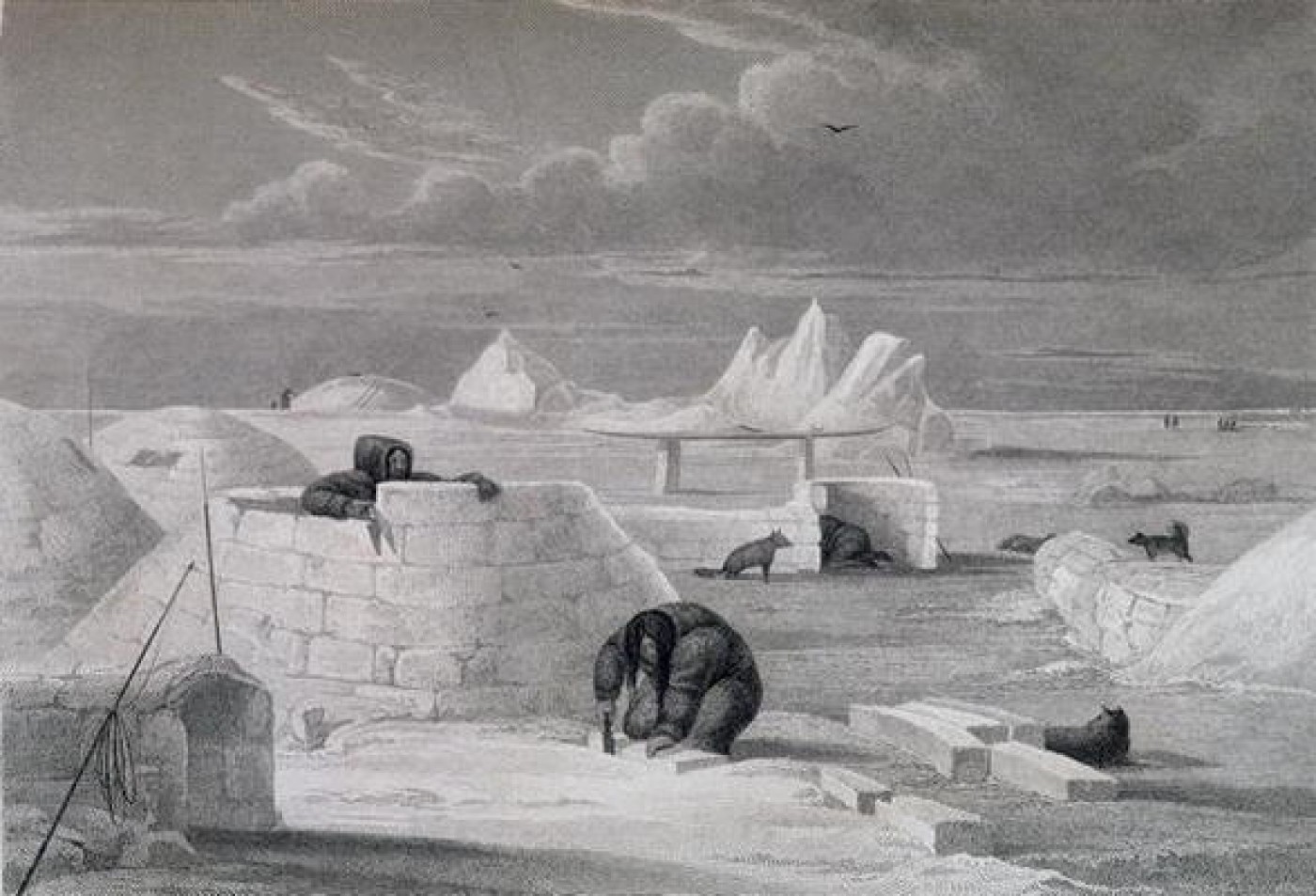

Journeying out from Hecla and Fury onto the ice, Parry, Lyon and a selection of the expedition’s company found that these ‘strange people’ were a party of Inuit. Hoping to trade strips of whalebone with the two ships, Parry and Lyon established friendly relations with the party. Exchanging small nails and beads for the whalebone, Parry and his men admired the patterns of some of the women’s clothes, before they began ‘to our utter astonishment and consternation to strip, though the thermometer stood at 23˚ below zero.'[7] Much to the relief of the officers, the women were wearing another layer of clothing underneath, and the party were invited to see the Inuit camp. Many of these scenes were immortalised in sketches by Lyon, and accounts of the Inuit way of life proved fascinating to anthropologists in Europe. As a gesture of goodwill, Parry invited the Inuit on board Hecla where the ship’s fiddler delighted them by playing them their songs; ‘they danced with the men for over an hour, and then returned in high glee and good humour to their huts.’ Over the course of the winter Parry and his men became accustomed to the frequent visits and encounters with the Inuit, using these experiences to record their customs and way of life. One encounter with an Inuit woman by the name of Iligliuk breathed fresh life into the expedition with a sketch of the coastline to the north. According to her, the Melville Peninsula ran steadily north before abruptly turning west to what was believed to be the edge of continental America. It was only in July 1822 that Hecla and Fury were finally able to free themselves from the ice and test this route.

Once again progress was slow and conditions proved harsh as the two ships battled their way north along the coastline. One of Hecla’s boats was destroyed by Fury’s bower anchor after the two ships collided, and Hecla almost caught fire from rope friction after an attempt to free herself from between two large ice floes. Discovering and naming Barrow’s River and passing an island referred to as ‘Igloolik’ Parry was faced with a channel westwards just as Iligliuk had sketched. To his dismay he was forced to turn back after being unable to find a clear path through the ice, but named this passage ‘Hecla and Fury Strait’. In September 1822 Lieutenant Reid undertook an overland 100 mile trek west along this strait before wintering at Igloolik with the intention of exploring the channel in the spring.

Once again interacting with the local Inuit, recording their culture, language and customs the two crews settled down for the long winter with the resumption of the theatre, study and cricket matches on the ice. In June 1823 Lyon attempted to cross the Melville Peninsula by dog sledge, the first naval officer to attempt a long distance journey in this fashion.[8] By the time he returned after thirteen days, Parry had made the decision to push forward through the icy strait without Hecla. However just a few days before Parry was set to depart from Igloolik disaster spelled the end of the expedition; Hecla’s ice master George Fife, died of scurvy. With fears of an outbreak among both crews and the ice offering no hope of further passage through the strait, Parry accepted the advice of the expedition’s surgeon, and set about his return to Britain. With the Arctic behind him Parry described the voyage as 'a matter of extreme disappointment.'[9] Reaching Lerwick in October 1823, the two ships were given a hero’s welcome as news of their exploits spread throughout the country and Parry learned by post he had been promoted to the rank of captain. He soon hastened to London and after a debrief with the Admiralty, Sir John Barrow once again requested Parry return to the Arctic. To the Admiralty’s delight, Parry accepted.

The third and final part of Max's blog will be posted next week. Watch this space!

- [1] Barrow's Boys, Fergus Fleming, pg.109

- [2] The Royal Navy in Polar Exploration from Frobisher to Ross, E C Coleman, pg. 233

- [3] Exploring Polar Frontiers: A Historical Encyclopaedia, Volume 1, William James Mills, pg. 504

- [4] The Royal Navy in Polar Exploration from Frobisher to Ross, E C Coleman, pg. 233

- [5] Journal of a Second Voyage for the Discovery of a North-West Passage from the Atlantic to the Pacific, Captain William Edward Parry, pg. 55

- [6] Journal of a Second Voyage for the Discovery of a North-West Passage from the Atlantic to the Pacific, Captain William Edward Parry, pg. 124

- [7] Journal of a Second Voyage for the Discovery of a North-West Passage from the Atlantic to the Pacific, Captain William Edward Parry, pg. 159

- [8] The Royal Navy in Polar Exploration from Frobisher to Ross, E C Coleman, pg. 122

- [9] Ships of Discovery and Exploration, LIncoln P Paine, pg. 78