Thursday, February 01 2018

One of the highlights of my job working with Project Undaunted is that I never know what I will find from one day to the next. The collection held by the Lloyd's Register Foundation (LRF) comprises survey reports, plans and correspondence that relate to specific ships that were surveyed between 1834 and the late 1960s. It is the most extensive collection of its kind with potential for ground breaking maritime study and research. These reports relate the condition, damage repairs, construction and modifications of the ships, as recorded by the Lloyd's Register (LR) surveyors during the course of their inspections. Project Undaunted aims to catalogue and digitise this vast collection with a view to making it accessible to the public.

For quite some time I have been cataloguing the earliest LRF records for the port of Leith. As the principal port for the city of Edinburgh and the southeast of Scotland, it has been fascinating to document the shipping history of Leith through the eyes of Lloyd's Register's long serving surveyor, Walter Paton. It was on one of these days digging through a mass of correspondence and survey reports that I came across an entry for a particularly remarkable ship. When Paton visited this ship at Dysart in 1835 he wrote ‘This is without exception the strongest I have met with.'[1] Paton found he was surveying one of the most well-known and celebrated vessels of her time. Famous throughout the world for her voyages of discovery to the Arctic in search of the fabled Northwest Passage; she had been sold into private hands and slipped into anonymity, her fate unknown. This article recounts the complete story of the ship Hecla, better known as HMS (His Majesty’s Ship) Hecla.

HMS Hecla was originally built as a Hecla Class bomb vessel, ordered by the Royal Navy on 5 June 1813.[2] Designed by Sir Henry Peake and constructed by the master shipbuilders Barksworth & Hawkes, of North Barton, Hull, she was launched on 22 July 1815. Hecla was a three masted full rigged ship, on a builders’ measurement tonnage of 375 24/94 and measured 105 feet in length.[3] Her armament consisted of one 13 inch mortar, one 10 inch mortar, eight 24 pounder carronades, and six 2 pounder guns. [4] Bomb vessels like Heclawere designed to hammer fixed land positions with heavy long distance mortar fire. These vessels were never intended for fighting in close quarters, and supported the fleet with a combination of both regular and explosive shot. Like many of her sister ships of the same class, Hecla was named after a volcano, in her case the Icelandic volcano Hekla.

Originally commissioned for service in the Mediterranean under Commander William Popham, Hecla saw action only once in her naval career; at the bombardment of Algiers on 27 August 1816. Following the failure of British diplomacy, Lord Exmouth headed a joint Anglo-Dutch attack to finally put an end to piracy and the Christian slave trade in the Ottoman Regency of Algeria. It was with heavy mortar fire that Hecla and her sister bomb ships, Beelzebub, Infernal, and Fury successfully blasted the Algerian coastal defences. Having contributed to the day’s victory, Hecla returned to England via Gibraltar and put in at Deptford while her fate was discussed at the Admiralty. By 1817, after the victory against Napoleonic rule in Europe and the woeful state of Britain’s national debt, the British government was no longer willing to support a wartime navy.[5] With severe reductions in naval strength and manpower and the sale or demolition of British warships, the future of vessels like Hecla appeared uncertain.

In November 1818, Arctic explorers HMS Isabella and HMS Alexander returned to London after less than ten months. Headed by Commander Sir John Ross, the expedition had been launched with the intention of exploring Baffin Bay and finding a Northwest Passage to the Pacific. Despite his unblemished naval record Ross appeared unwilling to explore the various passages in the ice, and declared that a range of mountains blocked the way through the Lancaster Sound. These he dubbed ‘Croker’s Mountains’, after the First Lord of the Admiralty. Much to the frustration of the appointed astronomer, Edward Sabine, and the second in command, Lieutenant Parry, Ross cut his expedition short and returned to Britain. Widely criticised, Ross’ expedition was regarded as a failure; the very existence of ‘Croker’s Mountains’ contested publicly. With the possibility of a Northwest Passage still hanging in the balance, the Admiralty Board agreed to fund a new expedition; this time under the command of the gifted Lieutenant William Edward Parry.[6]

Bomb vessels like Hecla became a popular choice for polar exploration during this period. Built to withstand the recoil of heavy mortar fire and to carry explosive materials, the strength and durability of the bombs made them an ideal choice to navigate the perilous regions of the Arctic. It was on 22 January 1819 that the Admiralty Board appointed Parry Lieutenant and Commander of Hecla. Nine days later operations began at Deptford to convert her for the purposes of Arctic exploration, cladding her with an additional three inches of oak and reinforcing her bows and hold beams with iron plates.

First Voyage to the Arctic 1819-1820

Parry’s orders from the Admiralty Board explained that he was to proceed north towards Baffin Island, into Sir James Lancaster Sound, and if able to find any passage westwards, push through the ice and make his way to the Behring’s Strait. If successful he was to put in at Kamchatka, pass copies of his journal to the Russian governor there, proceed to the Sandwich Islands or Canton, and then report back to Britain as soon as possible.[7]

With Parry commanding Hecla, he was to be accompanied in his mission by the 180 ton former gun brig Griper, under Parry’s long standing friend, Lieutenant Matthew Liddon. The entire crew would be on double pay, each man provided with a wolf-skin blanket, and the ships had been victualled with 12,000lb of carrots, 9,600 quarts of vegetable soup, 5,000 cans of beef, a vast supply of lemon juice, and over 1,000 gallons of rum.[8] These provisions were expected to last the expedition for up to two years, anything else needed would have to be caught or hunted, or traded for with the Inuit. After goodbyes had been said and the crowds of well-wishers had departed, HMS Hecla and HMS Griper left Britain on 11 May 1819.

Once the voyage was under way, Parry made fast progress, passing through the Davis Strait and reaching the entrance to the Lancaster Sound a month earlier than Ross had. During this time, Parry had been impressed with the speed and strength of Hecla, referring to her in his journal as ‘a charming ship’. However, due to the unsuitability of Griper to the icy conditions, Hecla had been forced to keep an easy half sail, often having to tow Griper for lengthy periods. Having reached the Lancaster Sound, the entire expedition now rested upon locating a passage to follow to the Pacific. Dozens of whale pods were sighted in the Sound and noted in the journals by Captain Sabine of the Royal Artillery, a friend of Parry and the official astronomer assigned to Ross’ expedition. With a clearly westerly wind prevailing, the progress of both ships was impeded and Griper was falling behind. It was at this point that Parry made the decision to push on in Hecla and rendezvous with Liddon in the middle of the Sound at 85˚ west. Backed by a wind pushing her further into the Lancaster Sound, two shores could be seen, rocky and mountainous to the south, and another, smooth and lower to the north. ‘The sea was open before us, free from ice or land’.[9] Parry had decisively proved that ‘Croker’s Mountains’ did not exist, and on 2 August 1819, Hecla sailed straight through them.

After re-joining Griper the expedition continued to push westwards. Over the course of the next few days, Parry set about naming the many bays, inlets and islands they passed; the most important being Croker Bay, Navy Board Inlet, and Admiralty Inlet. For much of this period, Parry and his officers were employed charting shoal waters, recording sightings of Arctic wildlife, and transferring large quantities of ice to both ships for drinking water. Their advance yielded the discovery of one smaller island, dubbed Prince Leopold Island, and a large inlet just before it on the south coast of the Sound. Further on, news from Hecla’scrow’s nest reported to Parry that a great expanse of ice blocked their westerly passage past Prince Leopold Island. Turning his attention south Hecla and Griper explored the inlet they had spotted for over 120 miles before they were once again hampered by impenetrable ice. On the 12 August 1819, the birthday of the Prince Regent, Parry named the inlet in his honour before finally turning back towards Lancaster Sound. Naming the strait to the west after the Secretary of the Admiralty, John Barrow, it was here that they waited for a gap in the ice.

As luck had it Parry chose the right option, and the ships were able to head northwest through a breach in the icefields on 21 August. Once able to proceed, Parry was anxious to exploit his good fortune and drove Hecla and Griper as quickly as the passage would allow, believing the sea to be navigable for only six more weeks.[10] On his push westwards Parry discovered and named Beechey Island, Wellington Channel, Cornwallis Island, Melville Island, and the whole archipelago the North Georgia Islands, later to become the Parry Islands. On 5 September 1819, following the conclusion of divine service, Parry informed the men that His Majesty’s ships Hecla and Griper had crossed the 110˚ west meridian. In these vessels Parry and his men had ventured further west into the Arctic Circle than any other known people, entitling them to a reward of £5000 granted by the King’s Order in Council and enacted in an Act of Parliament known as the Longitude Acts.[11] [12]

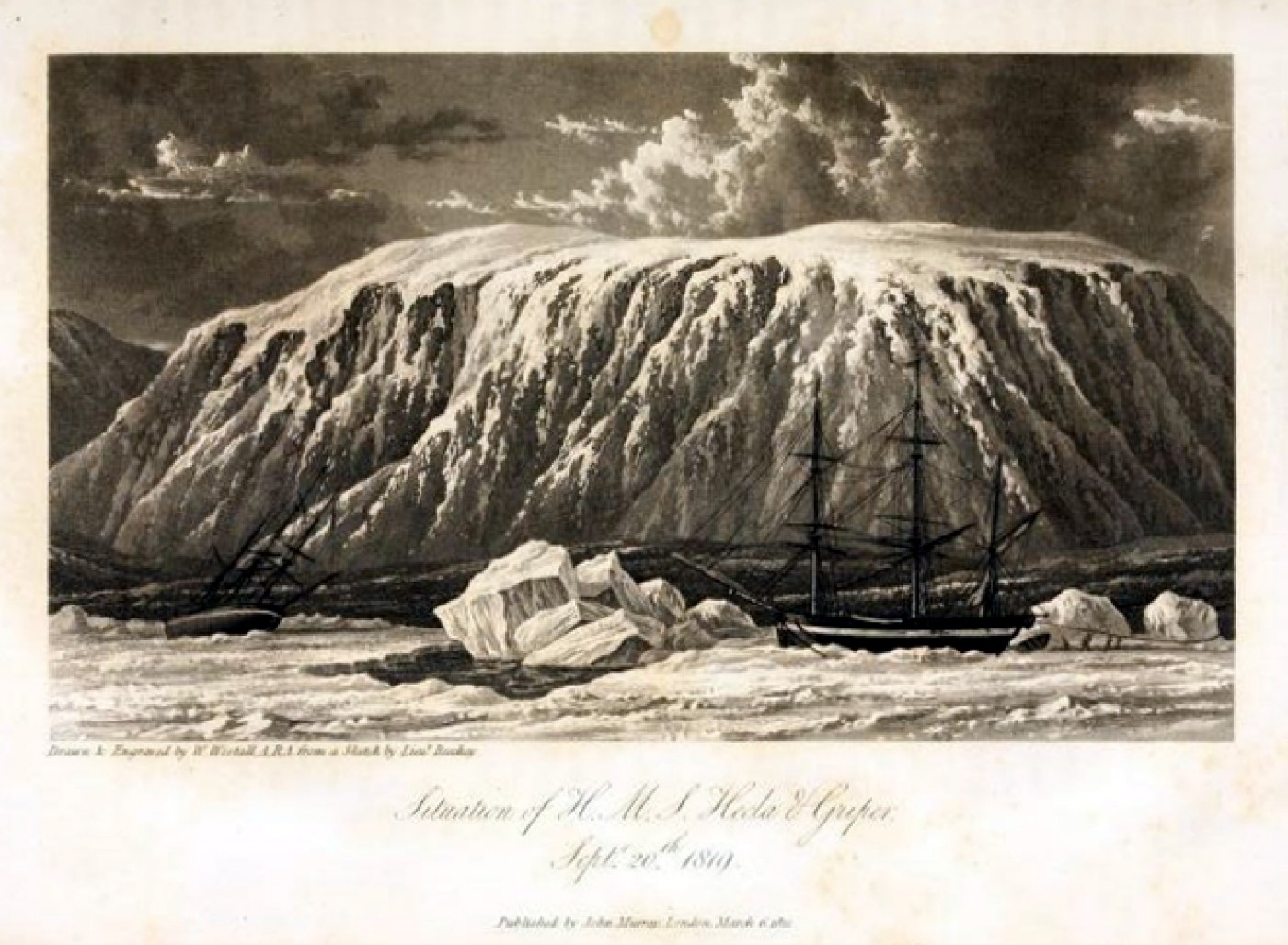

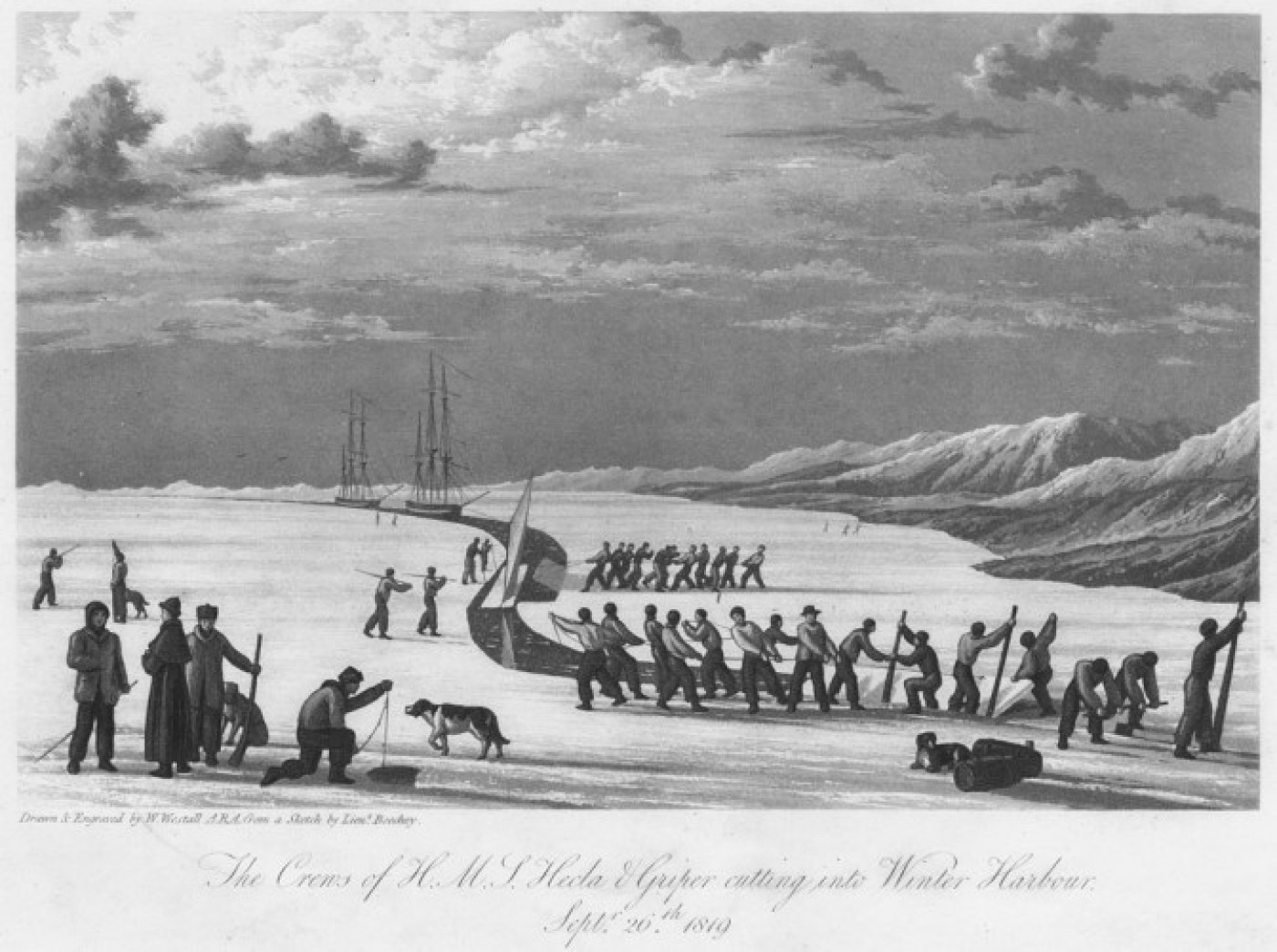

Spurred on by the reward, and the belief that the Northwest Passage could be navigated before the end of the season, the two ships ploughed on. As they progressed the strait became harder and harder to traverse, large sheets of ice increasingly blocking the path. After a small scientific excursion to the coast, Griper became stuck in the ice, trapped between the shore and a large ice floe that threatened to crush her. Parry began to make preparations for the removal of the crew and vital supplies, but thanks to the determination of Lieutenant Liddon they were able to extricate her. With navigation proving ever more perilous to the west and ice beginning to form on Hecla’s rigging, Parry took the decision to turn east and seek out winter quarters.[13] Winter approached far sooner than was expected and Heclaand Griper were forced to proceed eastwards as quickly as possible for fear of becoming trapped in the ice. In the search for a safe place to set anchor and wait out the long dark winter in the Arctic, Parry steered a course towards the south coast of Melville Island. Once again encountering a solid mass of ice blocking their way, with no other way to turn, the two crews set about cutting their way through towards what had been dubbed Hecla and Griper Bay. Having worked out a route the officers and men used saws to cut two parallel lines in the ice before cutting across and creating smaller and smaller slabs that could be pushed aside. In three days the two crews had created a canal nearly two and half miles long through seven inches of ice without incident.[14] By 26 September Hecla and Griper successfully anchored at Winter Harbour. In the fierce Arctic winter, this harbour was to be Hecla’s home for the next ten months.

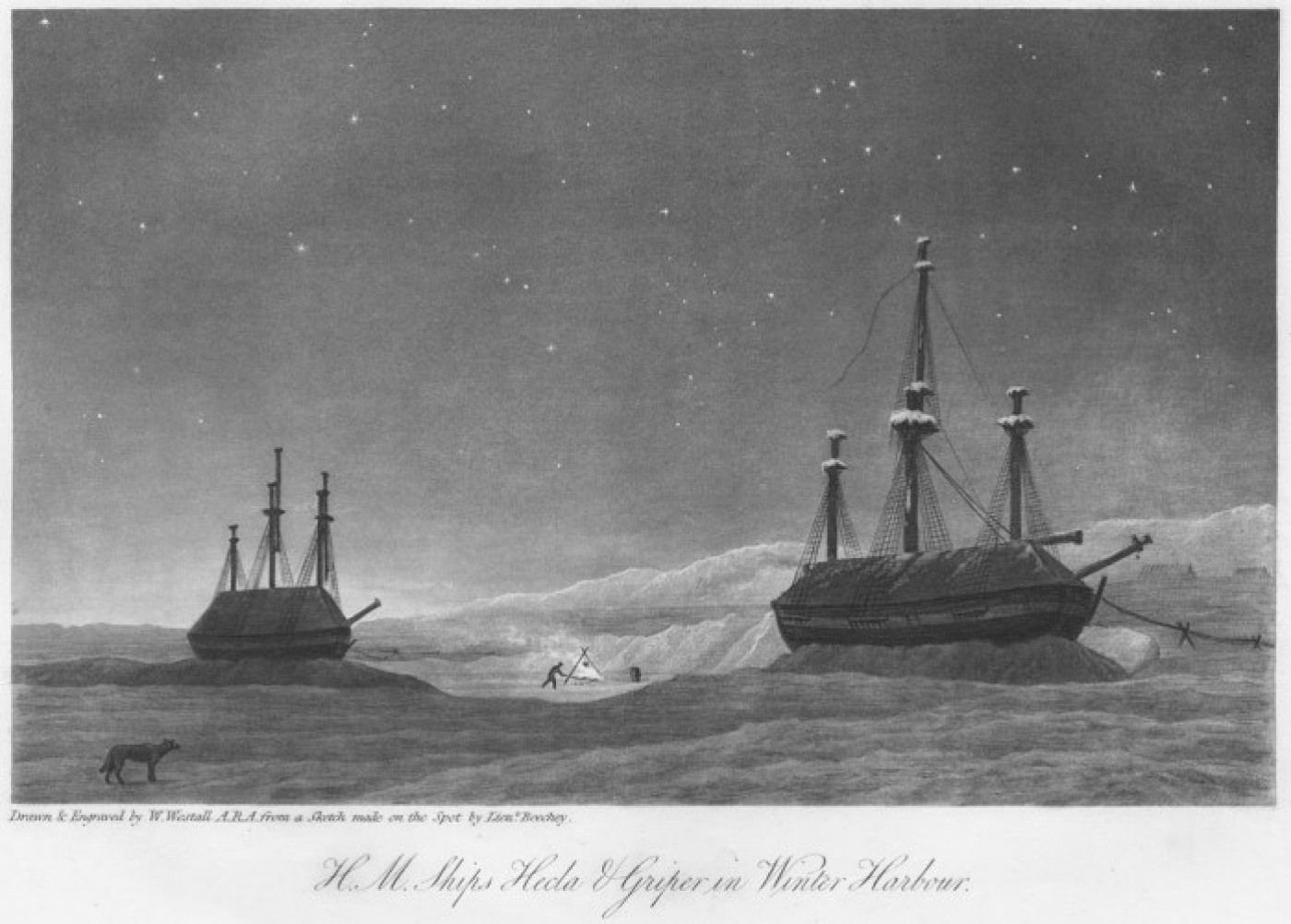

No other expedition had ever wintered with ships as far north as Parry was to attempt. Once docked the men set about securing the two vessels and preparing them for the long Arctic winter. Vital supplies, upper spars, rigging and boats were removed and safely buried in the snow, awnings were erected to cover the upper decks of the ships, and stove pipes were fitted for the circulation of warm air below decks. Rations were immediately reduced, procedures quickly put in place to keep clothes and bedding warm and dry, and weekly doctor’s inspections were arranged to check for early signs of scurvy. For the latter purpose daily rations of lime juice and sugar were issued. Trips to the shore were quickly organised for the purposes of securing fuel for the ships’ stoves, hunting game when the meat stores ran low, and for establishing vantage points for those venturing inland to find their way back to the ships. Work was also set about constructing a house for the expedition’s scientific instruments and an observatory for Sabine.

With frequent drills, hunting trips, and continual maintenance to Hecla and Griper the men were kept occupied. As Parry noted; ‘I dreaded the want of employment as one of the worst things that could befall us.'[15] Despite this steady routine the crew still had a great deal of free time, and with over ten months of winter, three of which in total darkness, Parry was determined to keep up morale. On the night of 5 November both crews were called to Heclafor the opening of the North Georgia Theatre and a performance of the play ‘Little Miss in Her Teens’ by Parry and his officers. A huge success, the decision was taken to perform a play every fortnight for the men, quickly adapting original writings from the crew when reading material became scarce. Just after the introduction of the theatre Edward Sabine began to produce an informative but light-hearted weekly newspaper, The North Georgia Gazette and Winter Chronicle. Relying on anonymous submissions, the paper boasted news updates, a theatre review, songs, poems and even adverts; all of which were copied into a book and circulated among the crew. Such entries recount the ‘distressing’ episode on board Hecla, namely ‘the non-cookery of our pies in proper time for dinner'[16] or ‘proposals for the eradication of snoring at night.'[17] Another common theme of the plays, poems and articles was the successful conclusion of the expedition; ‘when Behring’s Strait shall echo British cheers.'[18] In these amusing stories these pages show that the officers and men of Parry’s Expedition had not only survived the harsh Arctic winter, but also kept their good humour, retained their optimism, and thrived.

By February the sun was spotted and the temperature slowly rose, though it was another six months before the ice began to break and Hecla and Griper were ready to sail. During that time both ships’ companies carved a record of their stay on Melville Island on the landscapes only feature for miles around, a large boulder. Dubbed ‘Parry’s Rock’ it still stands today as a protected Canadian monument. After the lengthy stay at Winter Harbour Parry resolved to continue his push westwards; but to no avail. Navigating a treacherous path through ice floes that nearly crushed the two ships, halted at 113˚ 46’ 33” west Parry finally decided to turn back and search for another route to the south. On his return towards the Lancaster Sound Hecla sighted three whaling ships. Stopping to entrust one of them, Lee, with communications for the Admiralty, the Hecla and Griper learned of the coronation of King George IV, as well as news of Inuit sightings further east. Departing the area and heading towards the Inuit, it was not long before Inuit kayaks were spotted venturing towards Heclawith the intention of trading furs and whalebone for metal goods. After the conclusion of trade, the two vessels headed back towards Britain, crossing into the North Atlantic on 24 September. Strong gales on the way back to the Scottish port of Peterhead saw Hecla lose her bowsprit, foremast, mainmast, rigging and saw considerable damage to her sails.[19] Following the arrival at Peterhead, Parry left Lieutenant Beechey in command of Heclabefore departing for the Admiralty at London for presentation, only to discover that news from Lee of the expedition’s success had already reached them.

The Admiralty instantly promoted Parry to the rank of commander and the expedition was hailed a tremendous success. Though the Northwest Passage had not been discovered, HMS Hecla had successfully crossed the 110˚ west meridian, wintered at a latitude believed to be impossible, and had discovered over 850 miles of Arctic coastline. In Hecla Parry had achieved more than any other Arctic expedition, and it was not long afterwards that the Admiralty announced she was to be fitted out for a return voyage.

Keep your eyes on the Centre's social media channels for part two of our Hecla Rediscovered series!

- [1] Lloyd's Register Survey Report, Leith 131

- [2] British Warships in the Age of Sail 1793-1817, Rif Winfield, pg.377

- [3] British Warships in the Age of Sail 1793-1817, Rif Winfield, pg.377

- [4] Ships of Discovery and Exploration, Lincoln P Paine, pg.77

- [5] The Royal Navy Since 1815: A Short History, Eric Grove, pg.1

- [6] The Royal Navy in Polar Exploration from Frobisher to Ross, E C Coleman, pg. 169

- [7] The Royal Navy in Polar Exploration from Frobisher to Ross, E C Coleman, pg. 213

- [8] The Royal Navy in Polar Exploration from Frobisher to Ross, E C Coleman, pg. 214-215

- [9] Three Voyages for the Discovery of a North West Passage from the Atlantic to the Pacific, Sir W E Parry, Capt RN, pg.37

- [10] Three Voyages for the Discovery of a North West Passage from the Atlantic to the Pacific, Sir W E Parry, Capt RN, pg.61

- [11] Three Voyages for the Discovery of a North West Passage from the Atlantic to the Pacific, Sir W E Parry, Capt RN, pg.82

- [12] Granting of £5000 to the men of Hecla and Griper, 27/11/1820, RGO 14/1: 127r

- [13] The Royal Navy in Polar Exploration from Frobisher to Ross, E C Coleman, pg. 220

- [14] Three Voyages for the Discovery of a North West Passage from the Atlantic to the Pacific, Sir W E Parry, Capt RN, pg. 109

- [15] Three Voyages for the Discovery of a North West Passage from the Atlantic to the Pacific, Sir W E Parry, Capt RN, pg.129

- [16] North Georgia Gazette, Edward Sabine, pg.99

- [17] North Georgia Gazette, Edward Sabine, pg. 105

- [18] North Georgia Gazette, Edward Sabine, pg. 131

- [19] North Georgia Gazette, Edward Sabine, pg. 230