From the 1840s guano (bird manure) was highly prized for agriculture, especially that from Peru, but it was a perilous cargo for wooden sailing ships, causing fires, explosions, shipwrecks, a sickly odour, corrosion and timber decay, as well as spoiling other cargoes and harming the health of crews.

In order to enhance the fertility of the land, farmers had for centuries relied on the application of animal dung and materials like crushed bones and other recycled waste. Everything changed in the 19th century with guano (Spanish for manure) from Peru. 1 For more than 1,000 miles, countless small, rocky islands along its arid Pacific coastline were perfect breeding grounds for millions of seabirds, including petrels, penguins, pelicans, gannets and cormorants, who fed on the copious fish in the surrounding sea. Over the centuries vast deposits of guano formed on these barren islands, comprising bird droppings, dead birds, eggshells and fish remnants, and because it hardly ever rained, the guano was not leached of nutrients. Instead, it was rich in nitrogen and phosphorus, as well as ammonia. Long used by indigenous farmers, guano was little known in Europe until the early 19th century.2

Guano was commercially exploited in Peru from 1840, when millions of tons began to be exported, mainly from the Chincha Islands, 120 miles from the port of Callao, as well as the Lobos and Ballestas Islands. The trading company Antony Gibbs & Sons had substantial business interests in South America, and for two decades from 1842, they had a virtual monopoly in exporting guano from Peru. Much of the guano was purchased by farmers in Britain, because it gave remarkable results, especially when growing turnips and other root crops for animal feed. 3 William Gibbs became enormously wealthy and in 1843 purchased the estate of Tyntes Place near Bristol, which he renamed Tyntesfield and remodelled in the Victorian Gothic style (it is now a National Trust property). Guano was also obtained elsewhere across the world, but never on the scale or quality of Peru, though from 1843 hundreds of ships transported cargoes of guano from Ichaboe Island, off the west coast of Africa, until it was exhausted just two years later. 4 In the 1870s there was a shift to nitrates for fertilisers, by which time Peruvian guano was greatly depleted, though the industry continues today.

The Chincha Islands on a map of Peru in 1856

Guano deposits at the Chincha Islands, Peru

In 1849–50 Henry Mayhew, a journalist and social reformer, visited the Port of London when investigating the lives of London’s labouring classes for the Morning Chronicle. He learned about the wooden sailing vessels involved: ‘The South American traders are generally large ships, averaging from 500 to 800 tons, and carrying from twenty to thirty men, all told. The rate of wages is £2 a month. They sail at all times of the year, taking out cargoes of iron and general merchandise, and bringing back home hides, skins, tallow, horns, hoofs, bones, and guano.’ 5 Guano was known to cause problems, and so on arrival at Peru a ship was prepared to enable the cargo to be carried as safely as possible. Guano had an unpleasant odour, absorbed moisture (up to 20 per cent), overheated, produced gases, easily caught fire (which was difficult to extinguish), tainted other cargoes and stores, shifted, choked pumps, degraded ship timbers, corroded unpainted iron and steel and was a health hazard.

In 1858 Robert White Stevens, a printer at Plymouth and a Times correspondent, published On the Stowage of Ships and their Cargoes. He revealed what Antony Gibbs & Sons specified: ‘Owners find dunnage. Guano to be stowed so that a clear space may be left round the vessel, under the deck, for the purpose of examining the cargo and removing any water which may have been shipped.’ The hold was lined with dunnage (matting and pieces of wood) up to 2 feet thick to prevent the guano from absorbing moisture and to prevent decay to the ship’s timbers. He also recommended that the main deck should be caulked and coated with tar and that iron fittings should likewise be coated with tar to stop corrosion. 6

At the Chincha Islands, crews were not allowed ashore, but socialising nevertheless took place while the ships were waiting to load. John Remington Congdon, captain of the American barque Hannah Thornton, wrote in August 1853: ‘The fleet here is composed of 140 vessels, American, English, French, Russian, Italian, Dutch and Swede ... In our American fleet we have six ladies, captain’s wives; they visit each other often, and almost daily they are together on board of some ship ... We are all very neighbourly and help each other in all our troubles.’ George Washington Peck, a journalist and musician, was a passenger on board the American ship Albus, which arrived at the Chincha Islands in October 1853: ‘There are quite a number of ladies—the wives and daughters of captains in the fleet—and we make calls and visits and even have evening parties.’ On 1 November he compiled a list of 112 vessels waiting to be loaded, primarily from England and the United States. 7

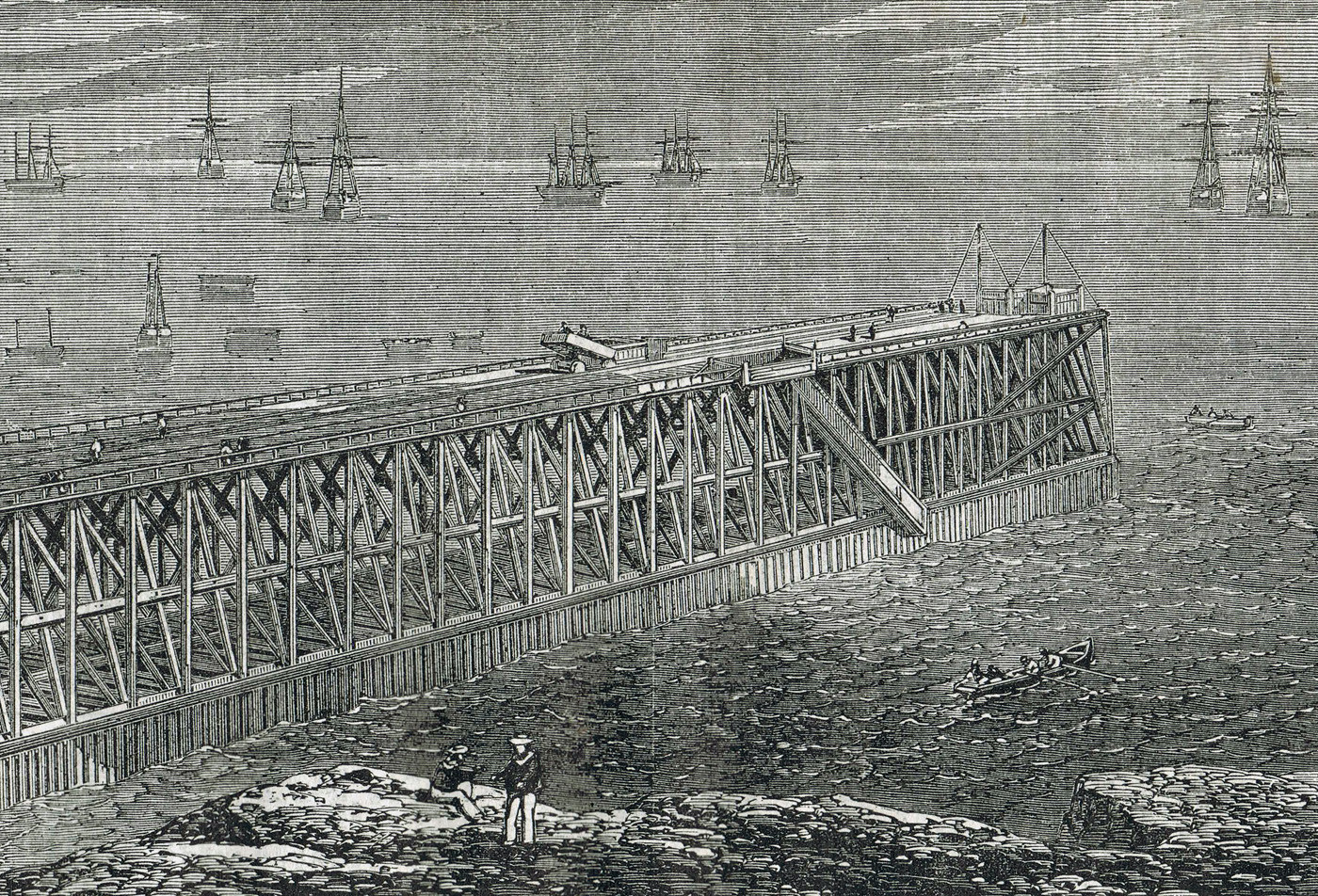

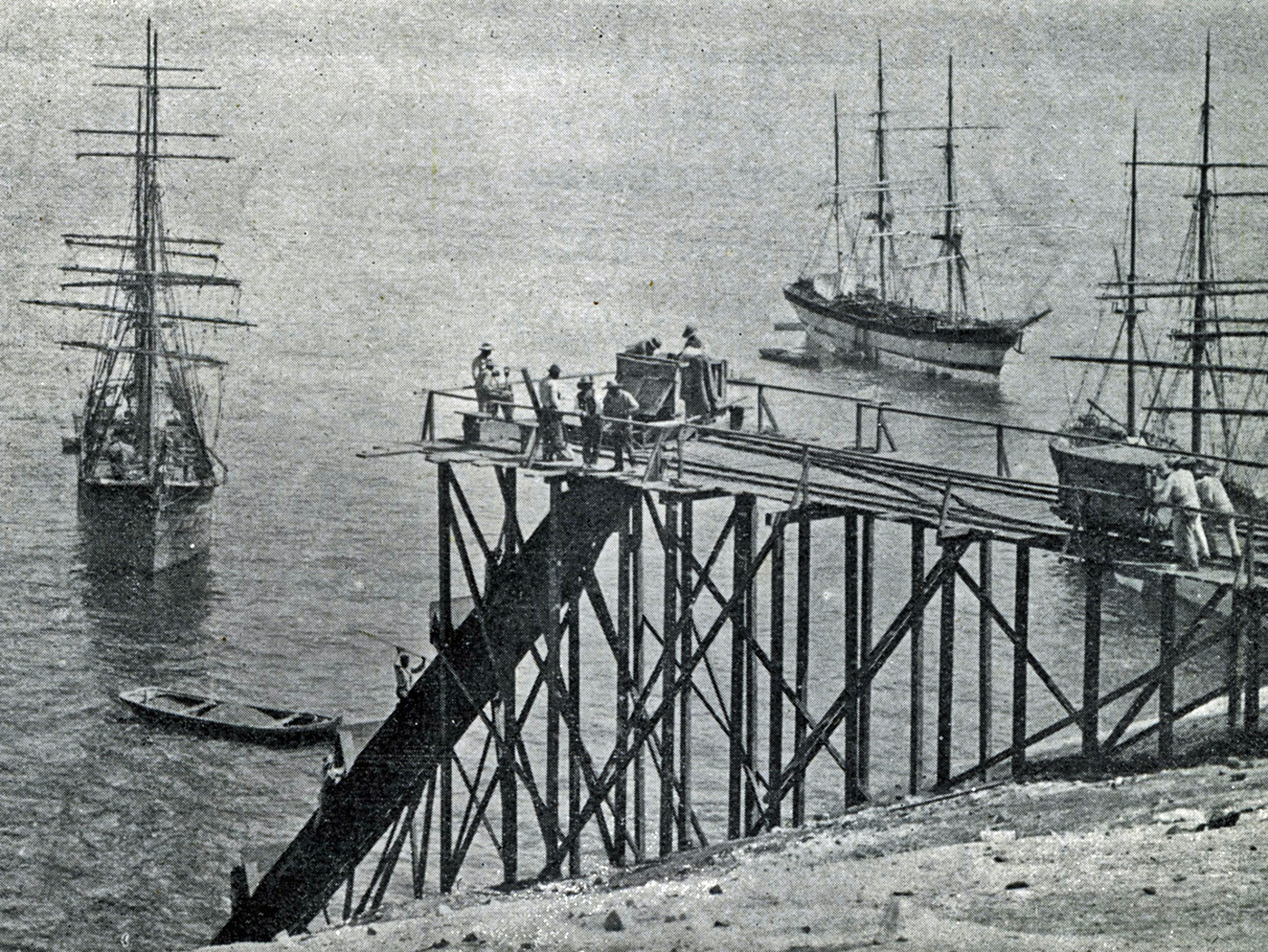

Ships waiting to load guano at the Chincha Islands in the early 1860s

Shipping at the Chincha Islands in 1862

In the intense heat, the digging and loading of guano, including the trimming of the cargo, were done by slave labour and later on by local Indians, convicts and thousands of indentured coolie labourers (effectively slaves, mostly from south China). Loading methods varied over time and in different locations and took up to three months, including a great deal of waiting. The first task was to remove much of the ship’s ballast. It was replaced with guano, which was brought to the cliff edge in wheelbarrows or rail trucks and tipped into boats or lighters, filling bags or sacks that were hauled aboard the merchant ships and down into the hold. Bags of guano were also stacked up the sides of a vessel as an additional protective lining. 8

A truck being loaded with guano in the early 1860s

Emptying guano into a chute from a railroad truck

The ship next moved towards the rocky shore and anchored beneath a timber and canvas chute or pipe (a ‘mangueras’), as was described in a first-hand account in the Leisure Hour for 1853: ‘Close to the face of the rock the water is deep enough to float the largest merchantman, and the steady constancy of the trade-wind, which rarely increases here beyond a pleasant breeze, enables the ship to lie in perfect safety in close contact with her two most dangerous enemies—a rocky island and a dead lee-shore.’ 9 Some years later, wooden moles (piers) were constructed, which jutted out into the sea and made the loading of guano somewhat easier.

Loading guano into boats in the early 1860s

A mole for loading guano at the Chincha Islands in 1862

Mayhew met one seaman at the Port of London who told him about the loading:

A shoot is made of canvas, equally square on all sides. The diggers bring the guano a quarter of a mile, to the shore ... There the diggers empty their bags, through an open place into the shoot which is spread below, and held by ropes. The shoot is then lowered down ... and the seamen who hold the ropes to regulate it must keep the lines a moving, to keep the guano from choking (going foul) in the shoots. We must regulate it by the pitch of the ship ... the shoot is emptied down the hatchways at a favourable moment. 10

Tons of loose guano poured into the hold, which was a wasteful method, as much fell into the sea, was carried away as dust or enveloped the ships, as Peck vividly recounted: ‘When a ship or launch is loading she is in a complete smother, as if ashes were poured into her ... you would hardly recognize some of the finest clippers, that before they left New York or Boston were praised in the papers.’ 11 Captain Congdon also commented on the dust: ‘Every part of the vessel is penetrated with this dust. It will go where smoke will ... The vessels are all of one color from truck to water.’ 12

Chutes for guano at the Chincha Islands in 1862

Loading guano into ships and boats using a chute

The Leisure Hour writer confirmed that dust got everywhere and was especially harmful to the workers:

The peculiar odour pervades the whole ship, the carefully tarred rigging becomes a dirty brown, while the snow-white decks and closely-furled sails assume the same dark hue ... the guano, after falling from so great an elevation, rises through the hatchways in one immense cloud, that completely envelops the ship, and renders the inhaling of anything save dust almost an impossibility. The men wear patent respirators, in the shape of bunches of tarry oakum (old rope), tied across their mouths and nostrils. 13

The loose guano needed to be carefully trimmed, distributing the weight fore and aft depending on the individual vessel, but the work was injurious, as Mayhew’s seaman observed: ‘It oft makes people’s noses bleed. The diggers on board and trimmers in the ship have to keep handkerchiefs round their noses, with oakum inside the handkerchiefs. It affects the eyes, too; no trimmer can work more than fifteen or twenty minutes at a time.’ 14 Sarah Everett, wife of the captain of the American clipper Kineo, wrote of her discomfort in a letter in January 1860: ‘If you should hold a bottle of hartshorn to your nose you can judge how our cabin smells. I can hardly get my breath, sometimes.’ She was referring to the commonly used smelling salts, or ammonium carbonate. As a vessel was loaded, Peck experienced an intense smell: ‘The ammonia is so strong that it is like entering a bottle of hartshorn to go into her interior—eyes and nose and lungs are all assailed at once.’ 15

Even in London, Mayhew was aware of the smell: ‘I may add that a cargo of guano was being unladen at the West India Dock on one of my visits there. It was hoisted out of the hold in bags, and had altogether the smell of very strong and unsound cheese. The whole atmosphere of the ship was cheesy.’ 16

According to Stevens, one way to improve conditions was to cover the surface of the guano: ‘A thin coating of gypsum or plaster of Paris moistened with sulphuric acid, laid over the top of the cargo, will, it is said, abate if not entirely remove the annoyance and danger of injury to the health of the ship’s crew; it can be removed again before discharging, and will readily sell for more than its cost.’ The effect on people’s health was not the only problem with guano. Cargoes of foodstuffs could become tainted, and Stevens gave an example of coffee berries: ‘The berries readily imbibe exhalations from other bodies, guano especially, and thereby acquire an adventitious and disagreeable flavour.’ 17

At the end of October 1857, the American barque Victor left the Chincha Islands with 600 tons of guano destined for Dunkirk in France. Although well prepared for carrying guano, the Victor started to leak after rounding Cape Horn. For six weeks the crew tried to save the vessel, but their pumps were constantly choked by guano dust. They then baled with canvas buckets, but these disintegrated owing to the corrosive nature of guano. The exhausted crew suffered terribly from ammonia, including burns on their hands. By good fortune on 7 March 1858, the sinking vessel was spotted in mid-Atlantic by the Enterprise brig of London. They were rescued and taken to Plymouth in Devon. A gold chronometer watch and chain were subsequently presented to the captain, with an engraved inscription: ‘The President of the United States of America to Capt. Isaac Heigho, of the British brig Enterprise, for his humane, zealous, and successful efforts in rescuing the master and crew of the American barque Victor from the perils of the sea. 1858.’ 18

Being prone to decomposing, heating and producing gases, guano was in danger of explosions and fires, which could not be readily extinguished with water, though barrels of water mixed with guano were prepared as a fire-retardant. Several vessels carrying guano were lost because of fire or suspected fires, amongst which was the Ann, a new barque from Sunderland, whose first voyage was to Ichaboe. Loaded with guano, she was almost home after sailing thousands of miles when on 8 April 1845 the vessel struck a sandbank off the Norfolk coast, close to Haisbro Sands. While trying to get off, seawater drenched the guano, setting off a fire, as recorded in the Hull Packet:

A volume of smoke rising through the hatchway warned the crew of this near danger, and induced their taking immediately to the boat without saving anything but themselves; and scarcely had they done so, when a tremendous explosion of the gas, engendered by the partially fired guano, blew the stern out of the vessel, which then filled, and sank in deep water. 19

Even if the fire had another cause, guano on board could still be catastrophic. On 11 March 1868, the Tudor was at Callao waiting to sail to Liverpool when a fire broke out. For three days, many vessels in the harbour tried to extinguish the flames, including HMS Mutine, whose commander, Henry M‘Clintock Alexander, described the events:

On March 11, at two a.m., a large merchant ship (the Tudor) took fire, and we had all hands at work to try to put it out, but without avail. The fire was bursting through her decks as she was towed on shore ... We were obliged to abandon her last night, and the sight was magnificent after dusk, as the flames rose to the masts, which soon fell over the side. She sank to-day and there is hardly a vestige to be seen of what was a magnificent ship, with 2,500 tons of guano. 20

Built at Quebec under Lloyd’s Register special survey in 1854, the Tudor was classed as A1. 21 She belonged to Samuel Robert Graves of Liverpool, a prominent shipowner, merchant, Member of Parliament and chairman of the Liverpool Shipowners Association. Her captain, Frederick Wherland, was also a lieutenant of the Royal Naval Reserve, and Commander Alexander of the Mutine commented: ‘The poor captain and his wife had lived on board ten years, and their grief was great’, before adding: ‘Had the fire not broken out when it did, in all human probability all hands would have perished.’ 22 If the Tudor had been at sea, she would have become just one of the many vessels listed as lost, with the location and cause unknown.

Ohlendorff’s Peruvian Guano

A fertile rural scene advertising guano

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the Lloyd’s Register Group or Lloyd’s Register Foundation.

National Trust Tyntesfield: https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/visit/bath-bristol/tyntesfield/history-of-tyntesfield

Bird guano: https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/62618

Visiting the Chincha Islands: https://www.audubon.org/news/holy-crap-trip-worlds-largest-guano-producing-islands

Footnotes

-

1

See Roy and Lesley Adkins 2021 When There Were Birds: The forgotten history of our connections (London: Little, Brown), pp 334–7. The word ‘guano’ originally derived from the Andean indigenous language Quechua, which refers to any form of dung used as an agricultural fertiliser.

-

2

Robert E Coker 1908 ‘The Fisheries and the Guano Industry of Peru’ Bulletin of the Bureau of Fisheries 28, pp 335–65; Robert E Coker 1920 ‘Habits and economic relations of the guano birds of Peru’ Proceedings of the United States National Museum 56, pp 449–511.

-

3

For the history of guano in Peru, see Gregory T Cushman 2013 Guano and the Opening of the Pacific World: A Global Ecological History (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press); Megan L Johnson 2017 ‘The English House of Gibbs in Peru’s Guano Trade in the Nineteenth Century’ All Theses. 2791 (https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/2791); Lesley J Kinsley 2019 Guano and British Victorians: An environmental history of a commodity of nature (University of Bristol PhD thesis).

-

4

James Miller 2003 Fertile Fortune: The Story of Tyntesfield (London: National Trust); Robert Craig 1964 ‘The African Guano Trade’ Mariner’s Mirror 60, pp 25–55. The trade became known as a white gold rush.

-

5

Morning Chronicle 11 March 1850, p 5.

-

6

Robert White Stevens 1858 On the Stowage of Ships and their Cargoes (Plymouth: Stevens; London: Longmans), p 72; Robert White Stevens 1871 (5th edn) On the Stowage of Ships and their Cargoes: with information regarding freights, charter-parties, &c &c (London: Longmans, Green, Reader & Dyer; Plymouth: R. White Stevens), pp 248–53; Mercantile Marine Magazine 8 (1861), pp 42–3.

-

7

John Remington Congdon 1853 ‘Chincha Guano Islands’ American Agriculturist 11, pp 99–100; George W Peck ‘The Chincha Islands’ The Working Farmer 6 no. 1, 1 March 1854, pp17–19.

-

8

Mercantile Marine Magazine 7 (1860), p 56; David B Clement 2021 Square-Rigger Sunset: The Passages of Four and Five-Masted Ships and Barques volume 1 (Exeter: The South West Maritime History Society), pp 171–82, 198; Cushman 2013, p 55; ‘A Visit to a Guano Island’ The Leisure Hour 7 July 1853, pp 433–6. For tiers of bags, see Stevens 1858, p 72 and 1871, p 250. For the workforce and guano production, see W M Mathew 1977 ‘A Primitive Export Sector: Guano Production in Mid-Nineteenth-Century Peru’ Journal of Latin American Studies 9, pp 35–57. For socialising, see Joan Druett 1998 Hen Frigates: Wives of Merchant Captains under Sail (London: Souvenir Press), pp 218–20.

-

9

See p 434 of ‘A Visit to a Guano Island’ The Leisure Hour 7 July 1853, pp 433–6.

-

10

Morning Chronicle 11 March 1850, p 5.

-

11

George W Peck ‘The Chincha Islands’ The Working Farmer 6 no. 1, 1 March 1954, pp 17–19.

-

12

Congdon 1853, p 99.

-

13

See p 434 of ‘A Visit to a Guano Island’ The Leisure Hour 7 July 1853, pp 433–6.

-

14

Morning Chronicle 11 March 1850, p 5. For trimming, see Clement 2021, p 111.

-

15

Maine Maritime Museum MS-478, cited in Druett 1998, pp 218–19; George W Peck 1854 Melbourne and the Chincha Islands; with sketches of Lima, and a voyage round the world (New York: Charles Scribner), pp 210–11.

-

16

Morning Chronicle 11 March 1850, p 5.

-

17

Stevens 1858, p 72; Stevens 1871, pp 127, 253.

-

18

Stevens 1871, pp 254–5 (who gives April, not March, for the sinking); Essex Standard 17 November 1858, p 2; Shipping and Mercantile Gazette 7 August 1858, p 4.

-

19

The Hull Packet 10 April 1845, p 4; see also Clement 2021, pp 171, 178.

-

20

The Army and Navy Gazette 25 April 1868, p 7.

-

21

-

22

The Army and Navy Gazette 25 April 1868, p 7