This article was written for the Rewriting Women into Maritime inititative by Lily Tidbury, Visitor and Sales Assistant Manager at Royal Museums Greenwich.

Isabella ‘Bella’ Keyzer (1922-1992)

Weaver, welder and Dundonian shipwright

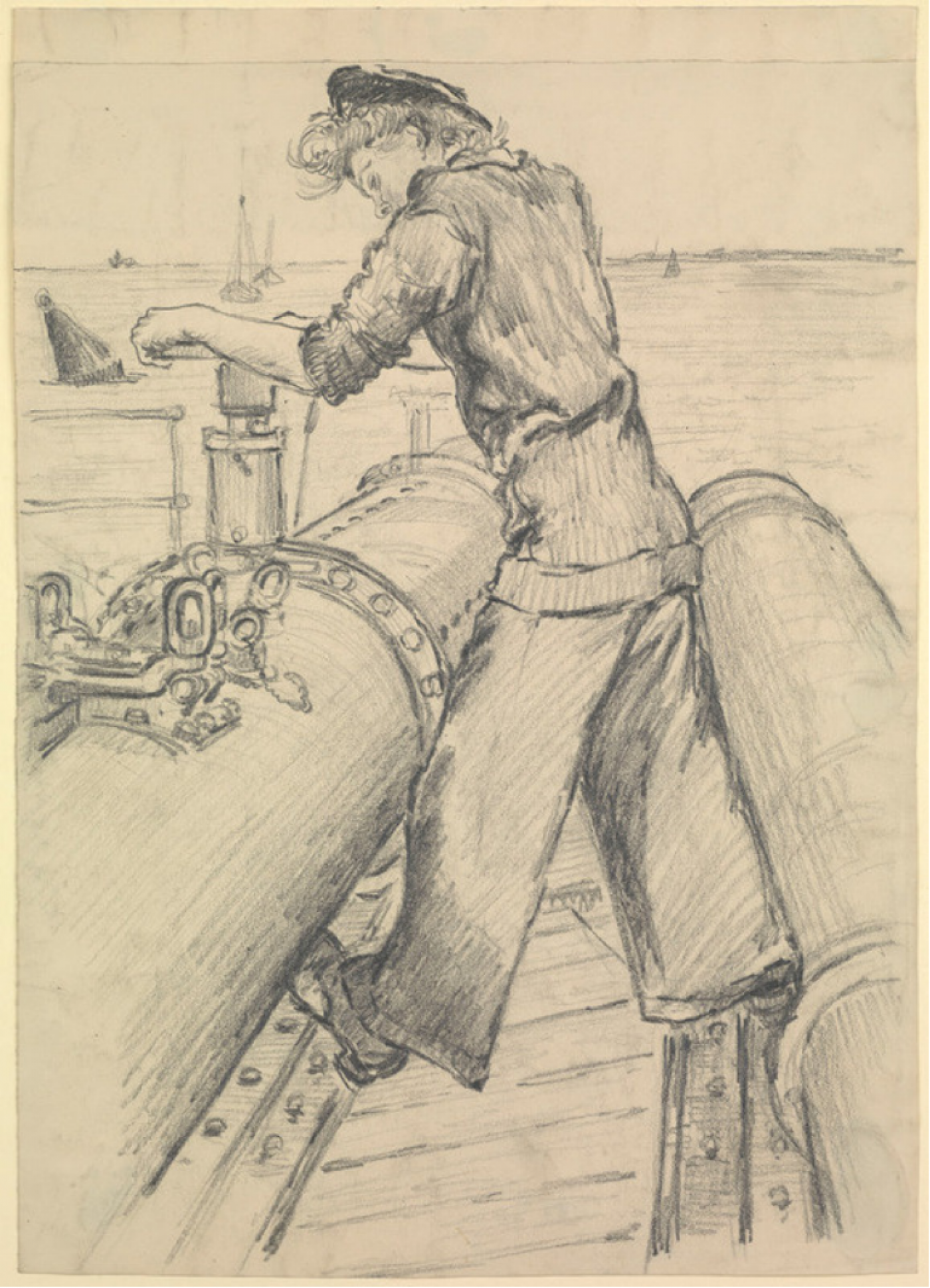

Sketch of Wren torpedo woman servicing torpedo tubes, by Gladys E. Reed, c.1943-44. © PY0090, National Maritime Museum

Statues in town squares, plaques on harbour walls; fathers, sons, brothers – almost every UK coastal settlement has stories of loss at sea, and memorials to go with them. Royal Museums Greenwich’s Maritime Memorials database is a crowdsourced encyclopaedia-style digital repository listing these commemorative sites for those lost at sea or in maritime endeavour. Although commemorating the dead is a timeless human process, the memorial landscapes of Western Europe and the US reflect dominant power structures and value-systems, nascent when widespread memorial construction emerged and persisting today.

In a database including every conceivable form of commemoration, those represented are overwhelmingly men. The Maritime Memorials project contains over 6000 entries. Around 25 of these - roughly 0.4% – memorialise women alone, not alongside male relatives. A further 0.1% of the entries commemorate women who perished directly because of their relationships with male seafarers – particularly wives of captains and surgeons, or family members travelling to men working in colonial administration. Memorials to women in the database are almost exclusively to passengers lost at sea – outliers including one yachtswoman and one W.R.N.S. member have been recorded, but thus far none to women in non-passenger commercial shipping. Regardless, the Maritime Memorials database shines a light on the lives and deeds of women working in maritime industries at a time when both their work, and appearance in the memorial landscape, was unusual.

Bella Keyzer, the youngest of three children, was born in Dundee in 1922. Raised in a well-read family of socialist ideals, with a brother whose middle name was Lenin, perhaps she was raised to challenge conventional wisdom about the possibilities her life would hold for her.

She met Dirk Keyzer, a chief engineer in the Dutch Royal Navy, at a dance in 1941 and became pregnant the same year. Having worked as a weaver in textile factories before the Second World War, factory work making munitions was not a sea-change for her when women’s wartime work began. She retrained as a welder in 1942 as the hours allowed her to spend more time with her young son, working at Caledon shipyard until 1945. There, she experienced some hostility from male colleagues, partly due to her son’s illegitimacy – Bella and Dirk had not married as he had been posted to the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia) before their child was born. Nonetheless, hard-working, straight-talking Bella was proud of her child and did not feel cowed by the stigma surrounding illegitimacy. She and Dirk married in November 1949 and moved to the Netherlands.

The Keyzer family returned to Scotland in 1957; Bella worked in assembly-line jobs but was dissatisfied with the lack of variety, skill, and pay. After training once again as a welder in 1976, she eventually secured a job with her old company. Over 500 ships were built in the Caledon yards from their opening in 1874 to closure in 1981. Victoria Drummond, the first female British marine engineer, had apprenticed at Caledon, finishing her apprenticeship there in 1920 – Bella, however, only secured a job there over 50 years later by applying as Mr. I Keyzer.

Bella Keyzer’s experience sheds light on the multiple threads and nuance permeating the struggle for women’s equality. As an individual, Bella’s story appears to challenge outdated dichotomies of feminine-coded and masculine-coded labour by balancing childcare and heavy industrial work – indeed, taking up welding for the sake of her son, burning through taboos and conventional gendered behaviours whilst reconciling this as part of ordinary economic and social life. Her example shows that individual pioneers of women’s equality could experience struggle against masculine norms as solitary, whilst simultaneously intuiting that these struggles are part of a broader tapestry of interconnectedness with family and community. Bella Keyzer’s experience as a multilingual welder, weaver, mother, and individual displays all the richness and nuance of women’s history and feminism that we must keep in mind going forward.

Bella expressed that her struggle for equal opportunity often felt isolating and that part of her drive was simply to make ends meet financially. In a 1985 interview with the Dundee Oral History project, she criticised the perception that women only became involved in trades once men were conscripted in the First and Second World Wars. Despite this, when describing her impact on women’s equality, she felt she threw a pebble in the water and made a wave, saying ‘it wis a very, very small wave, but it wis my wave’. An appropriately maritime metaphor – though understated - for a woman whose trailblazing path through Dundee’s shipyards elevated not only her own opportunities but those of women in maritime decades into the future. She received an award from Dundee District Council in 1992 for promoting women’s equality and is commemorated by a blue plaque near the Tay Road Bridge as part of the Dundee Women’s Trail.

Back to the exhibition home page.