This article was written for the Rewriting Women into Maritime inititative by Dr Jo Stanley, on behalf of Nautilus International

Introduction to Officer pioneers of the 1970s, contributed by Nautilus International

When we think of women in the 1970s workplace, we might envisage put-upon secretaries with lecherous male bosses, or female factory workers whose skills with a sewing machine were less valued than those of a male welder.

Yet, for the first time in history, employment law was starting to be on women's side. In the UK, the Equal Pay Act 1970 had prohibited any less favourable treatment between men and women in terms of pay and conditions of employment.

So even in the notoriously traditional Merchant Navy, we started to see young women choosing to train as deck, engineer and radio officers – attending nautical colleges alongside young men, getting jobs at sea on the same terms as their male counterparts, and joining the same maritime trade unions.

The union known today as Nautilus International is the result of several mergers of maritime unions in the UK, Netherlands and Switzerland over 150 years. In 1970s Britain, ships' officers would have joined one of two Nautilus predecessor unions: the MNAOA (Merchant Navy and Airline Officers' Association) or the REOU (Radio and Electronic Officers' Union).

Nautilus here celebrates the 1970s gender diversification of these unions by telling the stories of three officers who stood out from the crowd.

Linda Forbes

Deck Officer

Linda Craig Forbes was Scotland's first woman deck officer, though not by design. 'It never crossed my mind that I'd be a pioneering woman on ships,' she said. But when she saw an advert for sponsored deck cadetships, it didn't say 'boys only', so she sent in an application and got an interview.

Born in 1957 in Inverness, Linda had done well at school and initially hoped to become a veterinary surgeon, but there wasn't the money for her to train, and she needed to find a career with funding, so a Merchant Navy cadetship fitted the bill.

She didn't know of any seafarers in her family circle, but there were two adventurous female role models. An aunt had been a rare naval nursing sister in the Kenya Emergency (1952-60) and a great-aunt had 'gone up the Amazon in her 80s.'

As well as inheriting this family spirit, Linda was equipped for the Merchant Navy with determination, experience in handling two younger brothers, and a practical mindset. 'I was never a girlie girl,' she noted. 'My standard rig was casual, with trousers'.

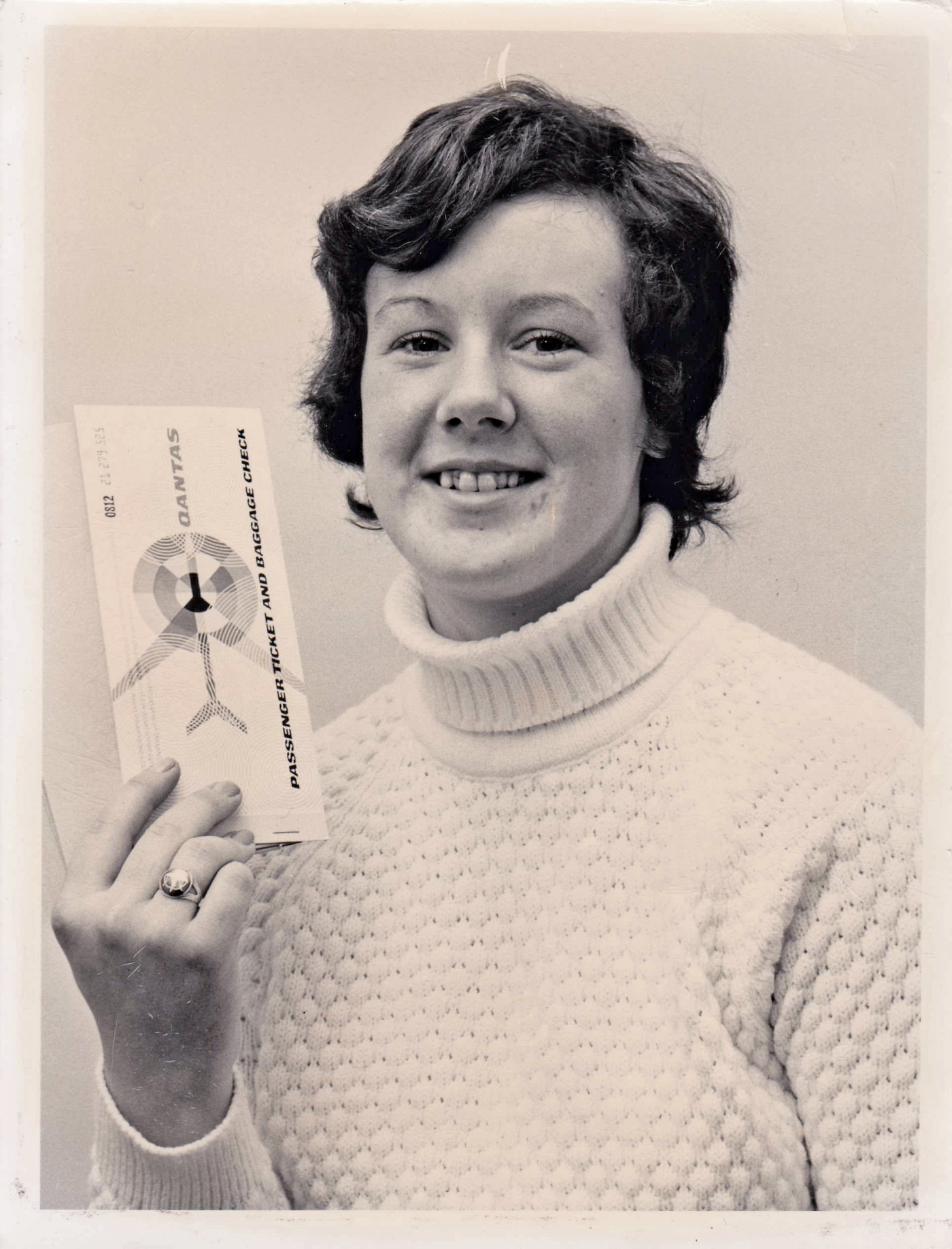

1970s deck officer Linda Craig Forbes with her airline ticket to Australia to join her first ship © Courtesy of Timothy Gascoyne

College and sea training

Linda's introduction to seafaring was at Glasgow College of Nautical Studies, where she was the only woman on her deck officer course and in the attached Sauchiehall Street hostel. She didn't recall any problems with her fellow trainees, but she had mixed feelings about being celebrated in newspapers as the 'first lady cadet in Scotland'.

Linda's first trip was with Scottish Ship Management Ltd on the new 14,651-ton grt Cape Grenville, which carried sand from Western Australia to Honolulu. Cadets were always treated as the lowest form of marine life and allocated the jobs no one else wanted to do. However, Linda felt 'I didn't get it any worse because I was a girl.'

She was happy to work on cargo vessels rather than passenger ships, not least because you could reach a higher rank more quickly. Usually the only woman onboard, she was joined occasionally by officers' wives.

Colleagues tended to be avuncular and helpful, especially if they were older men with daughters: 'If I was getting a rough deal at the hands of the stevedores, some of the crew would intervene to support me.'

Rising through the ranks

On qualifying as an officer of the watch, Linda served on Stephenson Clarke Shipping coastal bulk carriers, carrying coal to the London docks, and then worked for Turnbull Scott, and Dart (Canada) containers in the North Atlantic.

A career on all kinds of cargo vessels later saw her rise to second mate and chief mate. She funded her own training for the higher tickets. Her trade union membership card has gone by the wayside, but like all British deck officers of the time, she would have been a member of the Merchant Navy and Airline Officers' Association (MNAOA) – a predecessor of today's maritime union Nautilus International.

Challenges in the Middle East

She rarely had any problems getting crew to obey her orders, but her sea career ended partly because of gender. In the Persian/Arabian Gulf of the early 1980s, Linda found – like others before her – that the local men in the region often had trouble obeying women's orders, which meant that loading and unloading was expensively held up. Unfortunately, shipping companies saw that the fastest solution was to dispense with women deck officers rather than trying to change Arab men’s mindsets.

And the general recession didn't help. 'I think being female counted against me,' she reflected. Seemingly, shipping companies saw women as more expendable than men in times of trouble.

A productive life ashore

After leaving the sea in July 1981, Linda's careers included publishing and then renewables. She became procurement director for Scholastic, with a multi-million pound budget. She later held directorships of Caspium Ltd, Renewable Energy, Shelter & Environment Training Ltd, and Energency Ltd.

On top of work she gained a degree in engineering from the Open University, then two master's degrees in engineering and architecture.

In Orkney, she worked with the European Marine Energy Centre on marine renewables. She helped to set up Stromness Community Garden and was a valued board member of Orkney Housing Association. She was also a Passivhaus designer.

A member of the Women's Equality Party, she set up the Southport and West Lancashire group of the Fawcett Society in 2021. Her interests included bird watching, arts and crafts and genealogy, and she discovered to her surprise that one of her great-grandfathers had been a seafarer.

Strong to the end

Linda died aged 65 in December 2022, of cancer, in Southport's Queenscourt Hospice. She was annoyed that she would not reach 66 to be entitled to the state pension she had paid into for 49 years! Respecting her wishes, there was a private cremation. She left behind a partner, Timothy, and her memorabilia is being donated to appropriate archives.

Back to the exhibition home page.