This article was written for the Rewriting Women into Maritime inititative by Jennifer Robertson, Project Curator at Liverpool's Maritime Museum.

Eliza Plimsoll (1830-1882)

Campaigner for Seafarers

On the 22nd July 1875 the wife of a Liberal MP is challenged by a doorkeeper in the Houses of Parliament about the large bag she’s carrying. She explains her husband expects to be away from home and she has brought his night things. They allow her to proceed up to the Ladies’ Gallery with her bag. [1] Nothing about Eliza Plimsoll registers as a threat.

The Ladies’ Gallery in the House of Commons was separated from the chamber by a grille, designed to prevent the men becoming ‘distracted’ by the ladies and symbolising well the women’s exclusion from the seat of political power.[2] Not all women though would remain observers. Eliza may never have registered as a threat, but she was a force to be reckoned with and there was more than just her husband’s nightclothes in her bag.

Eliza’s husband was renowned campaigner for seafarers, Samuel Plimsoll. He’s best memorialised in the Plimsoll Line, the safe loading line he campaigned passionately for, and which bears his name. Yet, as one of his biographers said of Eliza:

“Without her there would surely be no such thing as the Plimsoll Line.” [3]

In an era when many cargo ships (grimly but accurately termed ‘coffin ships’) were sent out dangerously overloaded, a load line that would reveal if the ship was sitting too deep in the water to be safe had the potential to save thousands of merchant seafarers’ lives. It was Eliza who encouraged Samuel to take up this campaign.

By that day in July 1875, years of work had led to repeated frustrations attempting to get a bill through parliament that would ensure, among other things, a safe load line on ships. Another Merchant Shipping bill was due to be debated but neither of the Plimsolls could have been optimistic, there had been too many prior setbacks and plans had been laid should the bill be thwarted.

Plimsoll medallion, front view showing the profile of Samuel Plimsoll with the date of his and Eliza’s protest in parliament, 1875. © Maritime Museum, National Museums Liverpool collections. 52.111.1

Plimsoll medallion, reverse view showing a ‘coffin ship’ struggling in rough seas. © Maritime Museum, National Museums Liverpool collections. 52.111.1

From the Ladies’ Gallery Eliza must have watched with frustration as Prime Minister Disraeli declared there was no time to debate the bill before summer recess and it would have to wait. Any delay meant more loss of life, more seafarers who would never return home to their loved ones. She would have seen her husband take to the floor of the Commons to deliver a rebuke to the government, (and unsympathetic members of his own party), that breached both parliamentary protocol and good manners. He shouted and shook his fist in a display of rage and disappointment that feels too genuine to have been entirely pre-planned. What had been pre-planned though were Eliza’s actions that followed. The Press Gallery was directly below, and she pulled printed copies of a written protest from her bag and scattered them down through the grille.

Their actions in parliament swayed public opinion behind them, which helped to finally pass a bill the following year, but it was Samuel's face alone on the medallion that was struck to commemorate the day. Eliza’s part in this story is often mentioned as a sideshow to her husband’s performance. However, they were in this, as in their married life, a double act. Dramatic as Samuel’s actions were, it was not often that the Press Gallery had found political statements literally raining down upon them, impossible to ignore, and they long remembered Eliza’s role that day.

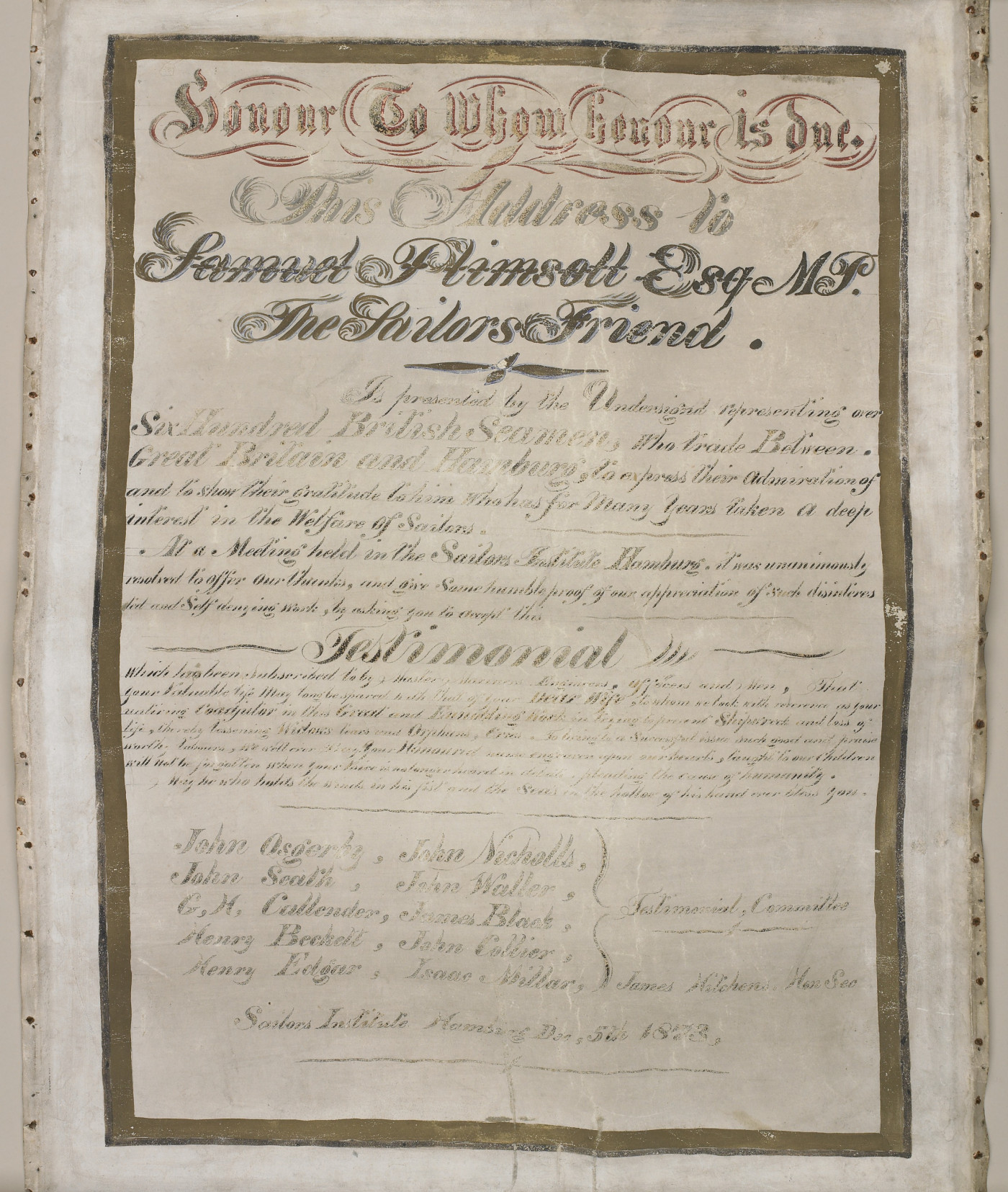

Testimonial from the Sailors’ Institute in Hamburg, 1876. © The Archives Centre, Maritime Museum, National Museums Liverpool collections. DX/1110

Eliza didn’t make public speeches, always preferring Samuel to speak for her. He deeply valued her thoughts and opinions. His speeches are full of her words; he would quote her verbatim. However, Eliza’s actions also spoke for her, and seafarers of the time saw in her the same devotion as her husband. In a beautiful testimonial address from the Sailors’ Institute in Hamburg they speak of her as his ‘untiring coadjutor.’

On the surface Eliza appeared to be a typical Victorian wife - quiet, supportive, remaining out of the limelight. In reality she was a driving force, not just in Samuel’s life but in his work that would help enshrine in law the safe load line concept still used today.

“Hers was the philosophy of patience and mature deliberation, whereas he imported into public matters the precipitancy of an impassioned earnestness.” [4]

It was a perfect partnership; he brought all the passion and showmanship to drive their cause forward while Eliza brought staunch good sense and the calm needed to keep him on course.

Eliza wasn’t the only woman vital to the campaign. She was honorary secretary to the Ladies’ Plimsoll Committee, a group of intelligent and well-informed women who were every bit as important to the cause as the men associated with it, but far less well remembered. We tend to remember the loudest voices, often men, but there are a plethora of quiet, dedicated people like Eliza without whom reform may never have come about.

Back to the exhibition home page.

- [1] The Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser, Saturday 14th October 1882 p. 4

- [3] Nicolette Jones, The Plimsoll Sensation, p. 37

- [4] The Rotherham Advertiser as quoted in George Peters, The Plimsoll Line, p. 148