This article was written for the Rewriting Women into Maritime inititative by Sarah Robinson, Senior Journalist at Nautilus International.

Introduction to Officer pioneers of the 1970s, contributed by Nautilus International

When we think of women in the 1970s workplace, we might envisage put-upon secretaries with lecherous male bosses, or female factory workers whose skills with a sewing machine were less valued than those of a male welder.

Yet, for the first time in history, employment law was starting to be on women's side. In the UK, the Equal Pay Act 1970 had prohibited any less favourable treatment between men and women in terms of pay and conditions of employment.

So even in the notoriously traditional Merchant Navy, we started to see young women choosing to train as deck, engineer and radio officers – attending nautical colleges alongside young men, getting jobs at sea on the same terms as their male counterparts, and joining the same maritime trade unions.

The union known today as Nautilus International is the result of several mergers of maritime unions in the UK, Netherlands and Switzerland over 150 years. In 1970s Britain, ships' officers would have joined one of two Nautilus predecessor unions: the MNAOA (Merchant Navy and Airline Officers' Association) or the REOU (Radio and Electronic Officers' Union).

Nautilus here celebrates the 1970s gender diversification of these unions by telling the stories of three officers who stood out from the crowd.

Rose King

Radio Officer

Life is often a game of chance, and Rose King's maritime career is a case in point.

Born in Britain, Rose spent the latter part of her childhood in South Africa, and on leaving school in Cape Town, she took a job in a department store. 'It was boring and I wanted a change,' she recalls, 'so when I saw a job advertised at the Union-Castle Line office next door, I decided to apply for that instead.'

This one spontaneous decision was how Rose ended up with a lifelong career in the shipping industry. Her first job involved booking cabins for passengers on Union-Castle's ships, and later she moved to the company's accounts office in London.

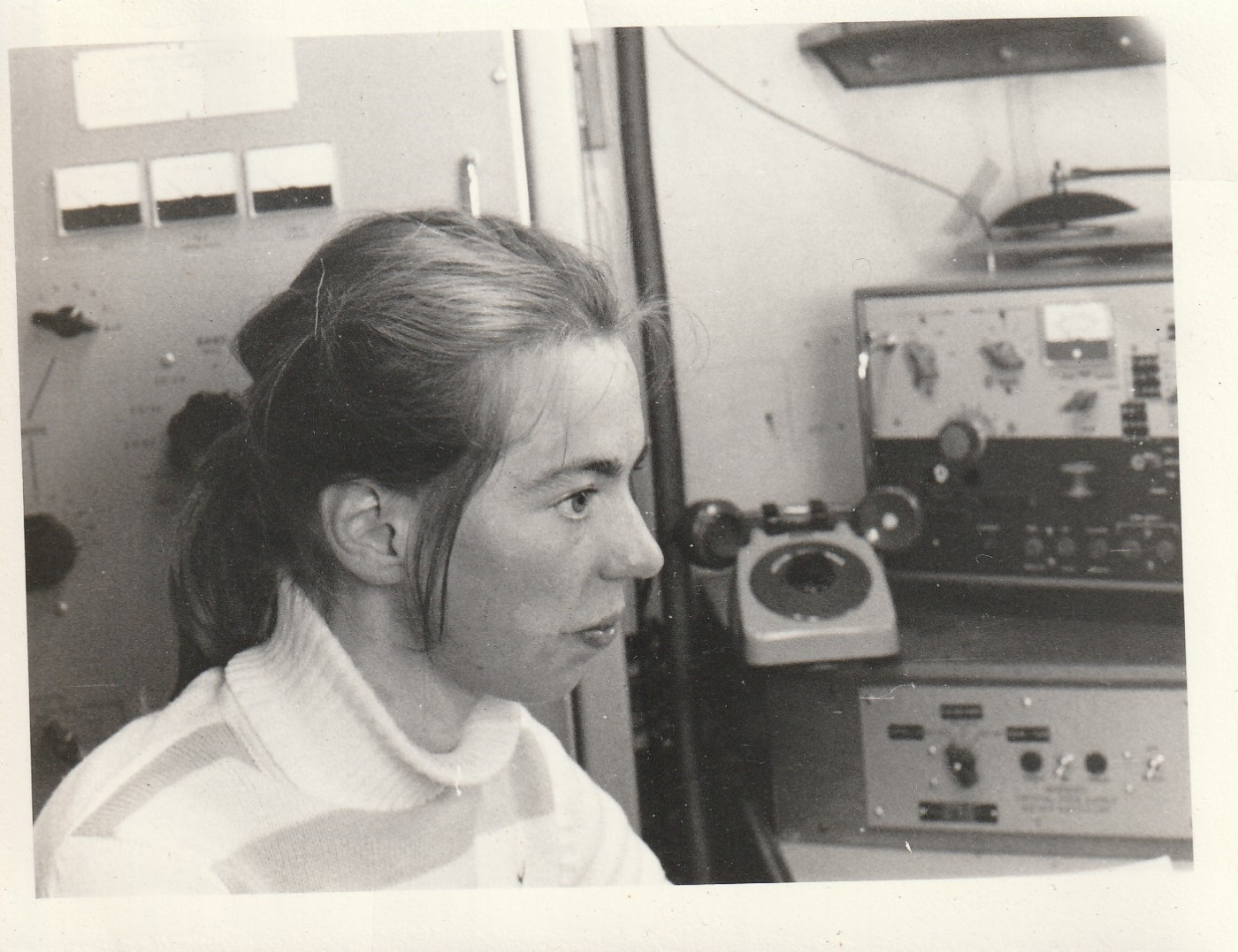

1970s radio officer Rose King shouldering the responsibility of communications onboard RRS Discovery in 1975 © Courtesy of Rose King

From shore to sea

Rose was still keeping her career options open, and it was through another random happening that she ended up as a radio officer. Always an avid reader, she came across a maritime book in her local public library in which a shipmaster wrote very interestingly about his career at sea.

'There was advice at the end about how to do it yourself – so I thought that could be me.'

There was nothing in the book about careers at sea being only for boys, so that was encouraging, but it did say that deck and engineering cadetships usually started between the ages of 16 and 18. As Rose was 21 by then, she noted that radio officer courses would take older students, and therefore decided that this would be her path.

'Then I wrote off to some colleges, got some replies and chose Lowestoft because the fees were fairly cheap and I'd been there before on holiday,' she says simply.

Unlike deck and engineer officer training, employer-sponsored cadetships were not available for radio officers, but Rose won an educational grant from the County Council of Hertfordshire, where she lived.

Good times in Lowestoft

The year was 1971 when Rose arrived at Lowestoft College on the east coast of England. It turned out that she was the first female student ever to join the radio officer course there, but Rose took that very much in her stride. 'I wasn't bothered, but the college must have told the BBC because a crew from the local news programme Look East turned up to interview me. I was lodging at the YMCA at the time, and my friends and I all crowded into the TV room to see me!'

Rose found the male students on her course to be friendly, and the college had a good atmosphere, with students encouraged to take part in activities like putting on plays. It was also at college that Rose first joined the Radio and Electronic Officers' Union (REOU), a predecessor of Nautilus International.

A different way to be employed at sea

When she qualified after three years, her next step was not to apply for a job with a shipping company, but instead with a marine radio equipment manufacturer. Radio officers like Rose would be trained in the equipment of Redifon, Marconi or International Marine Radio and then deployed on vessels which had that equipment onboard.

As the years went by and this system became less common, Rose was also sometimes employed directly by shipping companies, and sometimes by maritime job agencies. She found that she preferred fixed-term contract work, and never stayed long-term with an individual shipping company. Her career took her onto container vessels, survey, offshore, general cargo, tankers and even military corvettes.

From radio officer to ETO

Through all these posts, Rose's own work was evolving. 'The radio officer job involved all the communications – first using Morse and radio telegraphy, all maintenance of the radio equipment and bridge electronic equipment including radar, direction finder, log and gyro. Then the job expanded to engine room electronics and equipment such as lifts.'

By the late 1980s, she could see that the role of radio officer was on the way out, and she undertook self-funded training at the University of Southampton to gain a City & Guilds qualification in marine electronics. She then sailed as an electro-technical officer (ETO) until her retirement in 2012.

Alone but not lonely

Throughout her career at sea, Rose was almost always the only woman in the crew. Luckily this didn't ever bother her. 'Well, radio officers usually worked on their own, which I liked, and then I was in a small team as an ETO. The men were generally all right, but if they weren't, you'd just have to tell them where to get off.

'There was once a master who said to me "I'm as randy as a badger," and my reply was 'Sorry, Captain. I have no idea as to the sexual habits of badgers,' and then I scarpered. He gave me no more trouble after that.

'It wasn't a career for a quiet, shy person but it was fine for me. The main advice I'd give anyone is to make sure you bring enough to read!'

Back to the exhibition home page.