Tuesday, January 15 2019

With the launch of the Centre’s brand new website, I thought it was high time I wrote another blog. Remarkably, it has been over a year since my last blog, so this is well overdue!

As you may have already seen, members of the HEC team have been writing blogs on their favourite ships from the ‘First and Famous’ collection. I too have chosen a favourite – Aquitania.

The Cunard passenger liner had an impressive career spanning almost four decades in which she survived two World Wars, a global depression and heavy competition from more competitive, modern liners. Named after the wealthiest Roman province in Gaul, Aquitania was one of the most extravagant ships of the period. Her opulent interiors gained a reputation among passengers, leading to her being given the complimentary nicknames of ‘Aristocrat of the Atlantic’ and ‘the Ship Beautiful’.

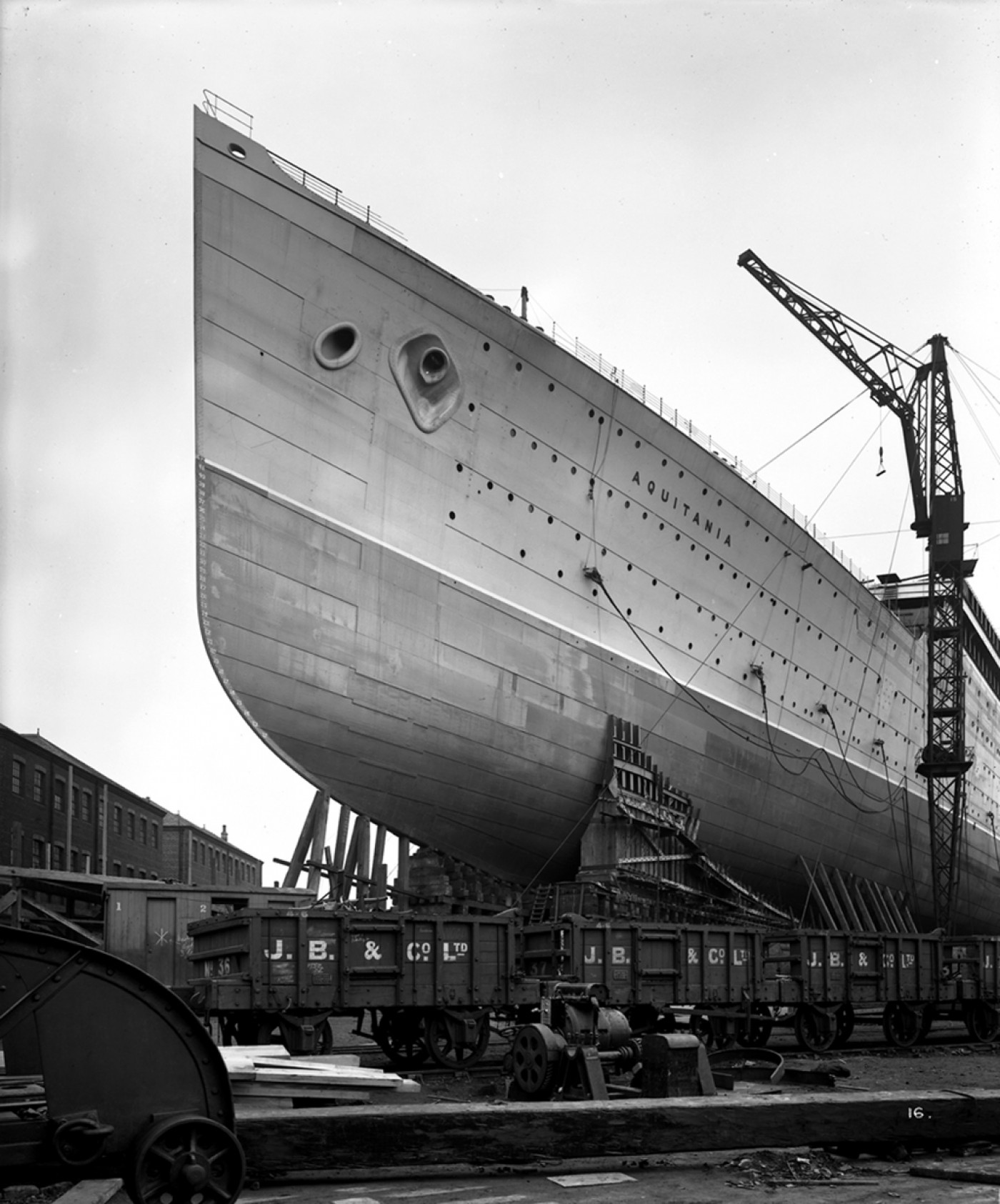

Aquitania was built by Clydebank shipbuilders John Brown & Company with design starting in earnest in 1907. Cunard would eventually approve the designs and place a contract for construction of the liner to begin in 1910. RMS Aquitania went on to become the third ‘Cunard Superliner’, navigating the popular transatlantic route with her sister liners RMS Mauretania and RMS Lusitania. The Cunard behemoth was powered by four, triple expansion Parsons steam turbines and could maintain a service speed of 23 knots (over 26 miles per hour).

Aquitania was launched on 21 April 1913 by the Countess of Derby Alice Stanley. Originally King George V was invited to attend but was unable to due to prior commitments. Over a year later Aquitania embarked on her maiden voyage from Liverpool to New York, departing on 30 May 1914. The voyage was a resounding success, which calmed some public fear over liner safety at the time. The day before Aquitania’s launch, the liner Empress of Ireland sank after a collision with collier Storstad, resulting in the death of 1,012 people.

The palatial interiors

Aquitania’s interiors were a sight to behold and boasted a range of facilities for passengers. Passenger capacity in 1914 was as follows:

- First Class – 618

- Second Class – 614

- Third Class – 1,198

Architectural firm Mewès & Davis were chosen by Cunard to design the interiors of the ship. The contract reportedly paid £5,000 (close to £300,000 in today’s money[1]). Architect Arthur Davis is credited with the bulk of the interior design of Aquitania. Davis incorporated features from other liners , such as a winter garden akin to the one found on Amerika. A permanent gardener was hired to maintain the various exotic foliage.

As to be expected, first class accommodation was of the highest quality, and offered a wide range of activities. First class passengers could bathe in an Egyptian Tiltman patterned swimming pool, visit the exquisite first-class lounge, complete with ceiling lunettes and a solid oak dancefloor or climb the steps of the main staircase inspired by Louis XVI’s Palace of Versailles.

Over the course of her service career, Aquitania underwent several refits. One of the most noteworthy additions to her facilities included the installation of a cinema in 1932.

Aquitania and the Great War

In July 1914, after only her third voyage across the Atlantic, Aquitania was thrust into the First World War having been requisitioned by the British Government. She was converted into an armed merchant cruiser and was fitted with all the ‘mod cons’ over a six day period. All ornaments and decorations onboard were removed and armaments were fitted.

Her career as an armed merchant cruiser was short-lived. On 22 August 1914, Aquitania collided with the Leyland Liner Canadian, an incident which caused Aquitania’s withdrawal from active duty. According to the Admiralty, Aquitania was too large to be an effective armed merchant cruiser. After repairs were undertaken and completed in late 1914, she was repurposed as a troopship. Her first voyages saw her carry over 5,000 troops from the 13th Division to the Dardenelles. Whilst transporting troops from Liverpool to Mudros in July 1915, Aquitania narrowly avoided a torpedo fired from a suspected Austrian submarine. The incident was a near miss with the torpedo passing ‘some fifty feet astern’[2].

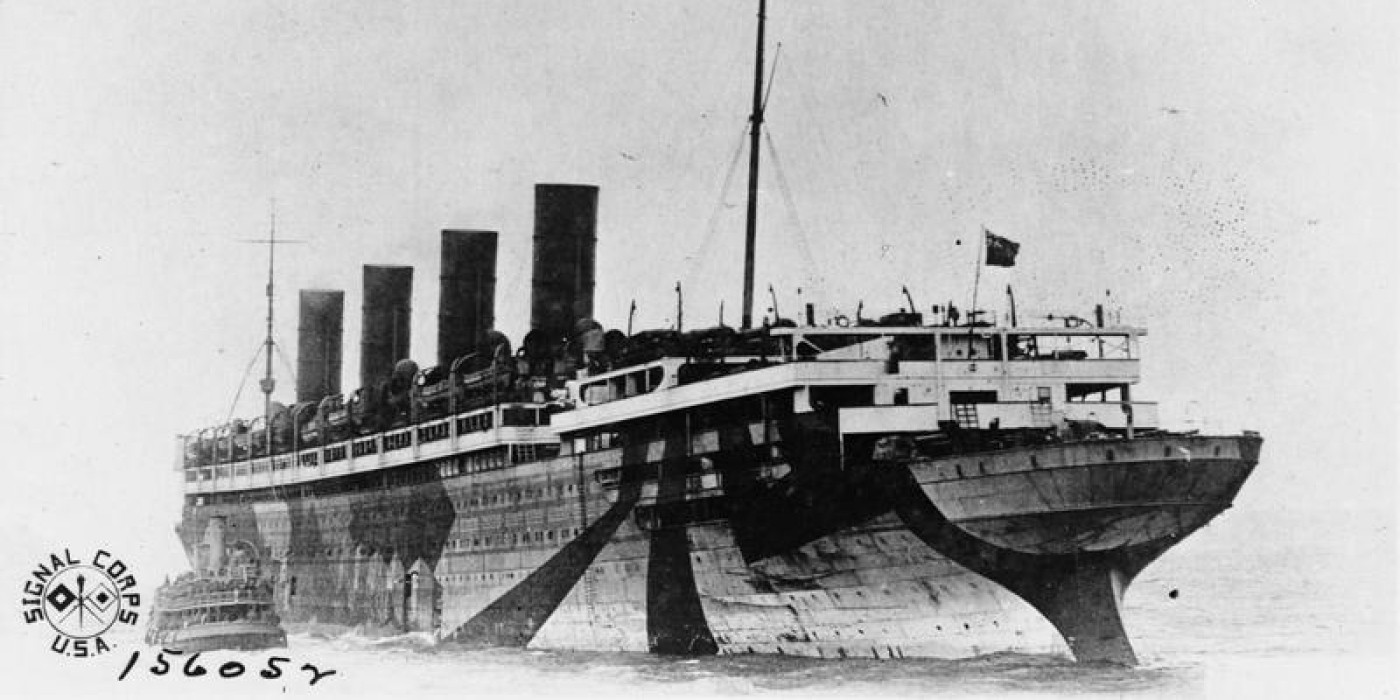

Britain’s failure at Gallipoli subjected Aquitania to yet another conversion that saw her fitted as a Hospital ship. To accommodate as many wounded as possible, several rooms onboard Aquitania were renovated, including the Carolean Smoking Room (pictured below) which was converted into a large ward. The ship was also given the internationally-recognised hospital ship colours, buff funnels, a white hull and broad green band. From early 1916 up until 1917, Aquitania safely carried 25,000 wounded troops.

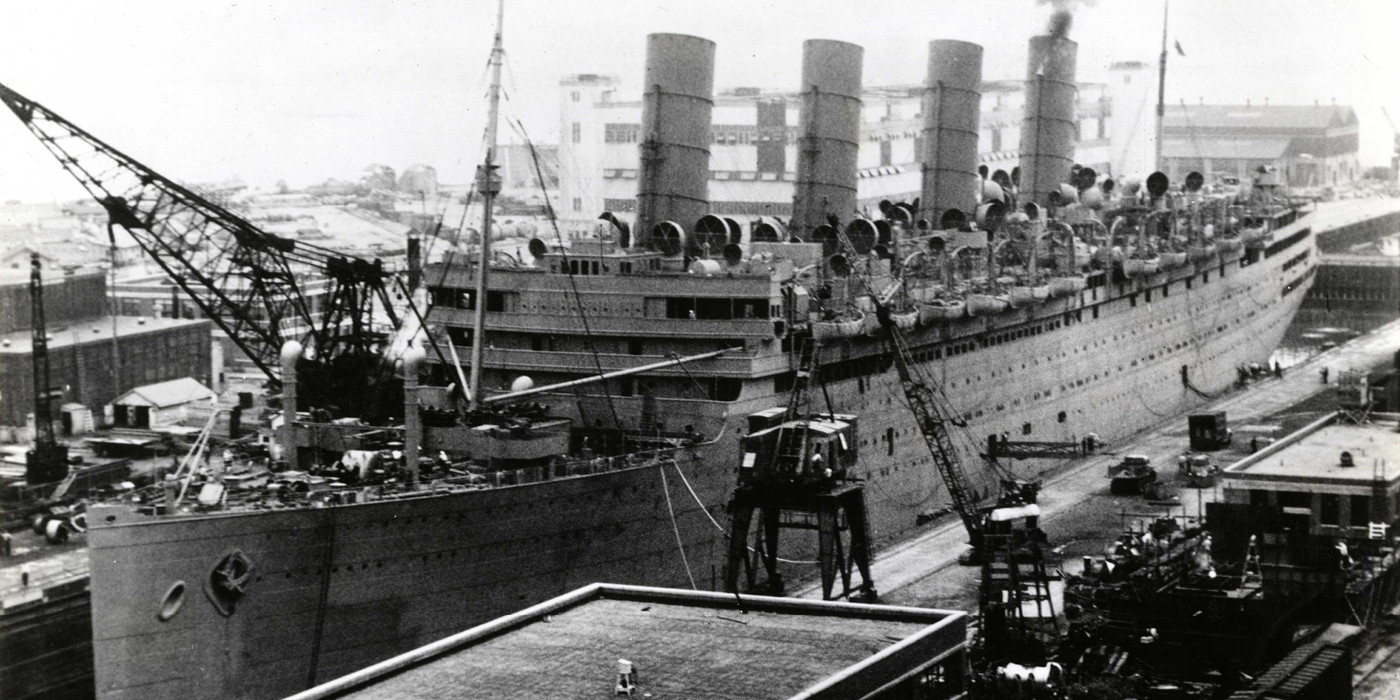

The final months of the Great War saw Aquitania once again serve as a troopship. She resumed commercial service in 1920, following a massive refit to ensure the vessel was suitable for passengers of all classes. The ship’s dazzle paint was removed, original furniture, artwork and ornaments installed (although much of the original furniture had to be replaced as it was damaged during wartime storage), a new wheelhouse was fitted and Aquitania’s coal bunkers were adapted to hold fuel oil. The conversion from coal to oil meant only 50 stokers were required, as opposed to the 350 needed to maintain coal fed bunkers.

Other additions during the refit included:

- A branch of Midland Bank was built for first class passengers

- Installation of an information bereau in the first class foyer

- A Sperry Mark IV Gyro Compass was installed, marking the first time such a device was ever used on a merchant ship

Back to commercial service

Shortly after her return to commercial service, Cunard announced in 1921 that Aquitania had broken the record for most passengers carried that year, numbering around 60,000 people.

One of the more amusing anecdotes about Aquitania regarded her transport of the famous British racehorse Papyrus in September 1923. The thoroughbred was journeying to a match race with the Kentucky Derby winner Zev. A special cabin had to be built to accommodate Papyrus, complete with specially fitted cushioned wall panelling. The bizarre story managed to reach international press outlets, with one such Australian newspaper reporting ‘A wireless message from the Cunard liner Aquitania, says the racehorse Papyrus was not disturbed by the heavy weather. He is being exercised around a padded cabin, ridden by a stable boy’.[3]

Shortly thereafter in 1924, changes in US immigration policy meant a major decrease in third class passenger numbers for Aquitania and the liner fleet as a whole. To ensure Aquitania remained financially viable, her crew was reduced from 1,200 to 850 (roughly 29%). Further decline soon after the Wall Street Crash and Great Depression prompted Cunard to send Aquitania on cruise routes in the Mediterranean. The resilience of Cunard during the recession ensured Aquitania stayed afloat (both physically and financially) and towards the end of the 1930s, passenger numbers began to increase once again and she returned to her previous Trans-Atlantic route.

[mul]Aquitania and the Second World War

Aquitania was requisitioned for military use on 18th November 1939, only two months after Britain declared war on Germany. Tasked with transporting Canadian forces, she was armed with anti-aircraft guns, submarine counter measures and two 6-inch guns at her stern. Throughout the Second World War, the grey liner served in the European and Pacific-Asian theatres. At the peak of her capacity, Aquitania could carry over 7,000 troops.

Noteworthy operations involving Aquitania during the War included the evacuation of civilians from Pearl Harbour (only two months after the port was infamously attacked by Japan) and the transportation of US and Canadian forces ahead of the Allied invasion of France.

The vessel remained in the hands of the Admiralty for a total of nine years, before her requisition was ended in 1948 at which point she was returned to Cunard.

The end of an era

In her final years Aquitania returned to commercial service, mainly operating on the Southampton/Halifax route until December 1949. At the turn of the year, Cunard had announced that Aquitania was to be withdrawn from active service and on 13th February, she was sold to the British Iron & Steel Corporation Ltd for scrapping.

Her illustrious career saw her steam an extraordinary 3,000,000 miles, or, the equivalent of 228 times the length of the Great Wall of China.

For almost 40 years Aquitania travelled the seas, whether under fire from submarines whilst carrying troops or entertaining aristocrats on a pleasure cruise in the Mediterranean. She is regarded as one of Cunard’s greatest liners. It came as no surprise that Aquitania was one of the first ships to be chosen to be included in ‘First and Famous’ pilot digitisation project. In fact in the initial draft for the 'First and Famous' ships list Aquitania was number 24 on a list of almost 230 ships. A fascinating vessel by all accounts, Aquitania really is one of the standout ships for me from the pilot.

View and download Aquitania’s digitised documents here.

[1] Currency Converter: 1270-2017 – The National Archives

[2] Aquitania Cunard’s Greatest Dream, Les Streater, 2009.

[3] The Ballarat Star, Tuesday 25 Sept 1923.