Maritime Innovation In Miniature

RMS Campania

This is the Ocean Liner RMS Campania. She was built for the Cunard Shipping Line on the River Clyde in Scotland and entered service on the Trans-Atlantic run in 1893.

The letters RMS stand for ‘Royal Mail Ship’ because Cunard had a lucrative Trans-Atlantic Mail contract with the Government-owned British Post Office.

Campania represented a striking change in the design of ocean liners. The first passenger liner to rely on steam power alone, her hull design required none of the traditional sailing ship features, such as the raked clipper bow and bowsprit. Campania’s bow is almost vertical.

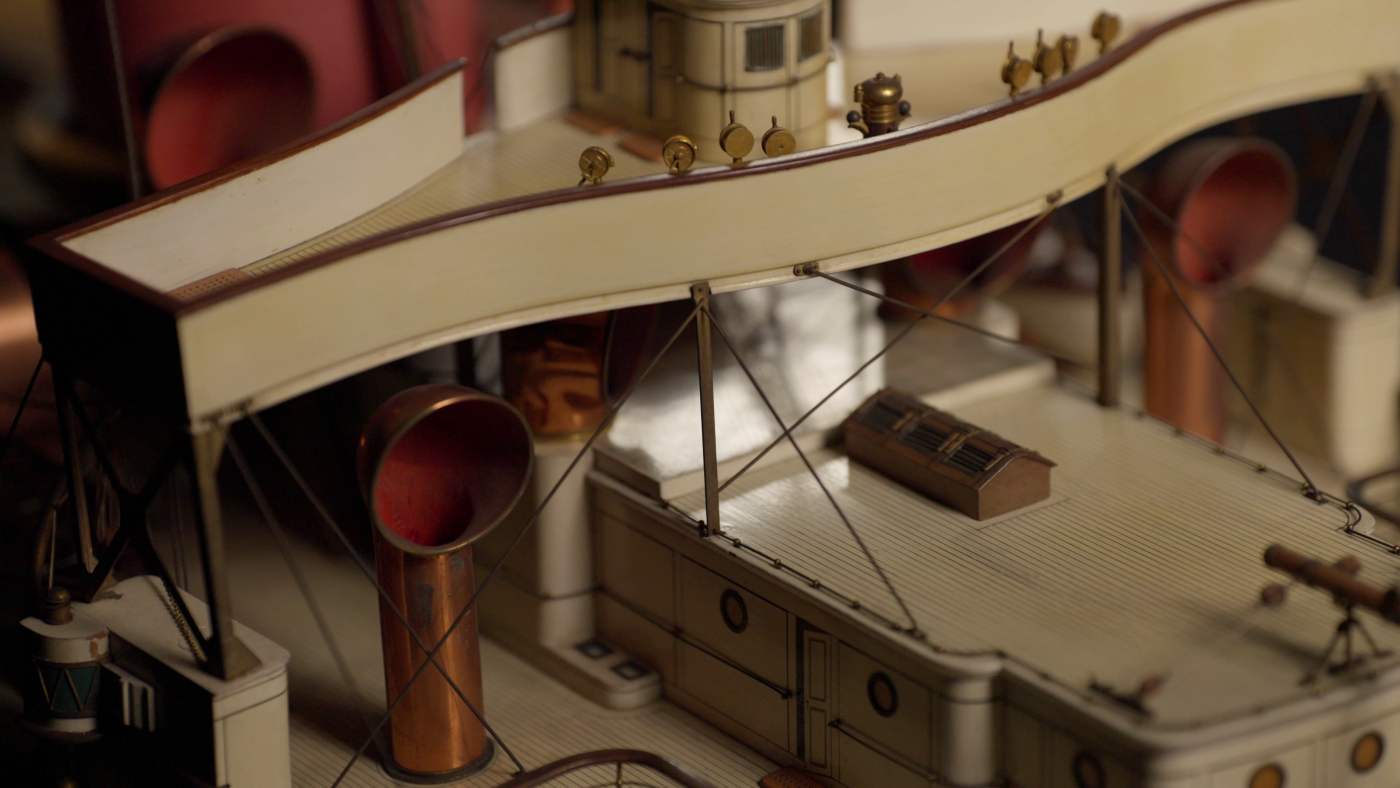

Her bridge was a radical new design, rising high above the decks and situated near the bow. With steamships increasing dramatically in size this was the only way to give the helmsman a view over the forecastle.

Her black hull, white superstructure, and red funnels with black caps & horizontal bands set a recognisable house-style for Cunard that would continue through the next half-century with great liners such as Lusitania and Mauritania.

When she entered service she was by some margin the largest passenger liner afloat at 12,950 gross registered tons and 622 feet long. She was also the fastest, breaking the record for both Westbound and Eastbound Trans-Atlantic passages, taking the coveted ‘Blue Riband’ at an average speed of over 21 knots, making a passage of under six days between Queenstown in Ireland and Sandy Hook in New York.

Her sister Lucania proved slightly faster in operation but between them they held the Blue Riband for fourteen years, an astonishing achievement in a period of great maritime innovation and competition.

The first Cunard liner to be fitted with twin propellers, she was powered by two huge triple-expansion five-cylinder piston engines delivering a combined 31,000 shaft horsepower. Each of the propellors measured 23ft 6ins in diameter and consisted of three bolted manganese blades.

The steam in her twelve double-ended scotch boilers was generated by a team of stokers who shovelled coal by hand into ninety-six furnaces. In this age before steam turbines her boilers ran at just 165 pounds per square inch and the direct-drive propellor shafts turning at a mere 79 revolutions per minute – but at the time this was the very height of marine engineering achievement.

Her deck is equipped with copper breakwaters. As steamships became larger and faster so the damage that water on deck could cause rose accordingly and these breakwaters directed the water safely back overboard.

Her main role was to carry passengers, and her six hundred first class passengers enjoyed the very height of Victorian opulence. The first-class smoking room was furnished in ‘Elizabethan style’, with oak panelling, and included an open fireplace, a ‘first’ for ocean liners. Extensive use was made of marble and there was also a hot water system and an extensive system of call-bells.

Four hundred second-class passengers could travel in fair comfort, while the thousand third-class passengers were berthed in what was derisively termed ‘steerage’. Built before the era of heavily regulated passenger safety, she had 20 lifeboats, with a total capacity to evacuate about half the number onboard.

Launching was by radial davits, slow to operate. Not until gravity davits were developed in the 1920s did launching lifeboats become quick and simple.

Internally Campania was sub-divided with the latest watertight doors that could be closed in emergency by bridge control. She was a ‘Two-compartment’ ship, which meant that she should stay afloat even with two compartments holed and flooded.

In 1901 she became the first liner fitted with ‘Marconi’ wireless telegraph and made history by being the first ship to exchange any form of information by wireless – and subsequently exchanged the first ever ice bulletin. Two years later, for the first time, radio was used in the ship to provide a news service for passengers.

In 1905 a freak wave hit the ship in the mid-Atlantic and 5 steerage passengers were swept away. And a further 29 passengers were injured. This was the first time Cunard had lost any passengers through accident.

When war broke out in 1914 Campania became one of the world’s first aircraft-carriers and the first ship ever modified to have a permanent flight deck.

Her anchors are particularly important as they played a major role in her loss in 1918.

When converted into a warship these original ‘admiralty’ pattern anchors were replaced by stockless anchors which were easier to handle. However, they had less holding power than these originals. On the night of 4/5 November 1918 she began to drag her anchor in the firth of forth and drifted out-of-control, smashing into the battleship Royal Oak, and the battlecruiser Glorious. Her hull damage was so severe that she sank. Her wreck is still there, a unique survivor of the rapid development of passenger liner technology at the start of the twentieth century and one of the world’s first ever aircraft carriers.