This article was written for the Rewriting Women into Maritime inititative by Dr Nina Baker OBE, Engineering Historian.

Female Ropemakers

Agency in the Age of Sail and after

Women workers from Gourock Ropeworks Co., Fleetwood 28 June 1930 © Courtesy of Dr Nina Baker’s private collection

In 1945, 14-year-old Isabel Heron (later Caddell) (1931-1995) started her first job, in the Govan ropeworks, Glasgow. She was doing ‘unskilled’ work in one of the larger Scottish ropeworks remaining in the mid-20th century. It would have been hot, noisy, very dusty and hard, hard work. The other women working there - and it was almost entirely women apart from a few male managers and mechanics - were hard too. This was working-class Glasgow. Most of the women came from the same sort of households as the tough men who worked in the nearby shipyards.

The language between the women was pretty foul. Isabel was so desperate to fit in that she started to speak the same way too. Fortunately, her older married friend, Annie, “… took her aside, told her off and told her it didn't suit her. That put a stop to that!” Arduous work and rough language were not enough to put Isabel off. She stayed on doing the work, “… holding the rope and twisting it…” until she married eight years later. [1]

Isabel © Ahmad, E. 2023.

The industry's rise and fall

Ropes of every size were, and are still, essential to shipping and many other industries. A three-masted ship of 1,250 tons deadweight tonnage (DWT) would require over 18 miles of cordage of a myriad of sizes from ½ inch up to 16 inches diameter, plus a lot of smaller twines and cords for canvas sewing or whipping ropes’ ends. [2]

To give you some idea of scale, HMS Victory is 2,162 tons DWT. The two largest container ships in the world in 2023, Loreta and Irina, were 240,000 DWT.

In the nineteenth century there had been hundreds of ropeworks, large and small, making cordage from natural fibres for all manner of uses (not just for ships) in all manner of sizes. By the 1860s the increasing industrialisation and mechanisation of the processes, such as hatchelling and yarn spinning had led to the change from a mostly male industry to one that had an increasing female majority. Women were cheaper. The proportions of women to men were generally at least 2:1 rising to 10:1.

However, even in the pre-industrialised era, some women were in ropemaking on their own account. Known women master ropemakers included:

- Helen Lindsay (aged 61 in 1851), Edinburgh. She employed two men and two boys.

- Isabella Rolland (1851 and 1861) She had inherited the business from her late husband, including some £2000 stock-in-trade and over £29,000 debts owed to the business (both sums at today’s values). She employed 2 journeymen and 3 apprentices.

- Janet Cameron (1871) Dunoon, employing 4 men and 4 boys.

These will not have been the only female proprietors in the trade in that era. It seems that such women were usually owners of very small businesses.

By the early twentieth century the number of ropeworks was diminishing sharply. In Scotland at the beginning of the 20th century there were about 200 rope and twine manufacturers. By 1923 there were 22,000 people in ropemaking in the UK as recorded under the Ministry of Labour national insurance scheme Two-thirds of them were women.

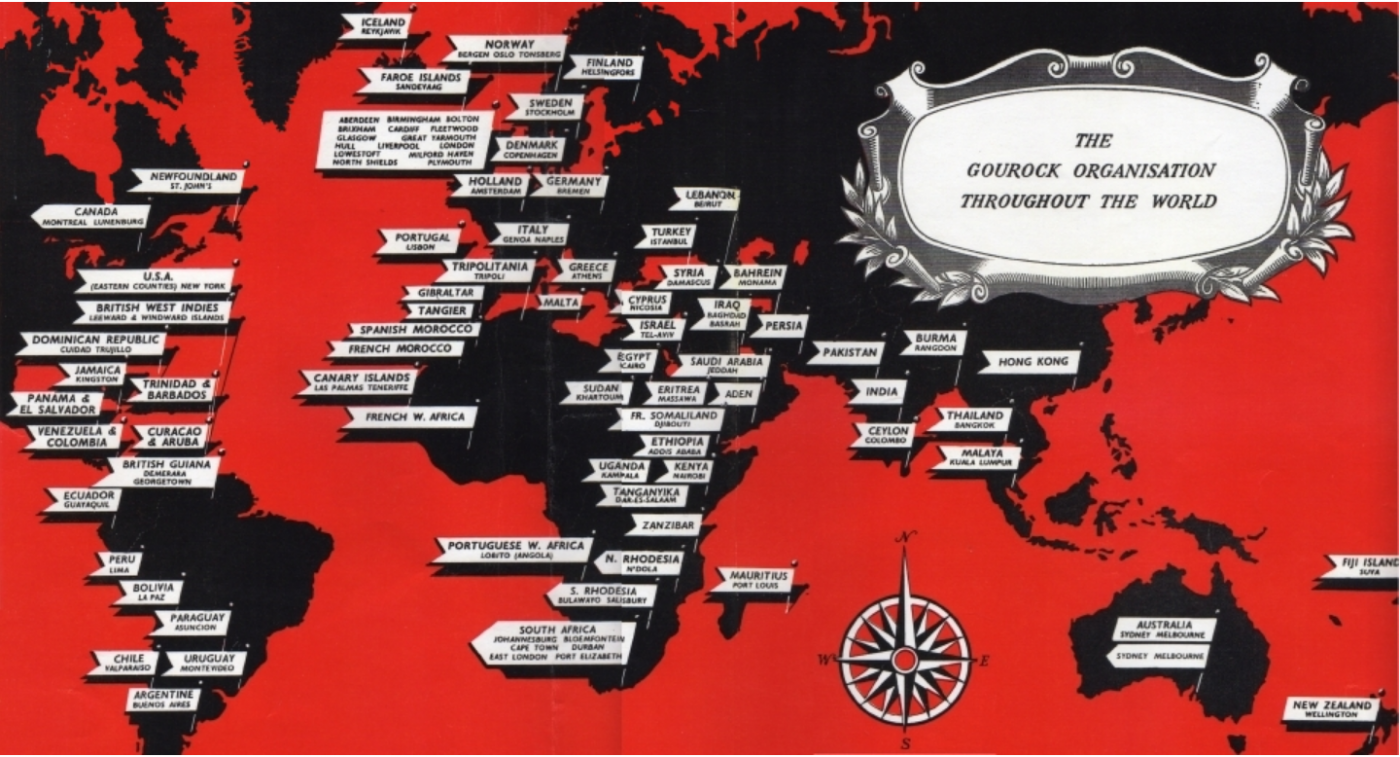

Gourock Rope Works Map © Courtesy of Gourock Inc.

The processes

The initial stages of ropemaking were similar to other plant-fibre (cotton, flax, jute etc) preparatory work in the textiles industries. Bales of fibres had to be divided and cleaned by drawing handfuls of the fibres through the spikes of a hackle/hatchel (hatchelling). A bundle of these combed-out fibres were wrapped around the worker’s waist. The first twist of yarn was fixed to a rotating hook on hand-turned wheel. This wheel was rotated, usually by a boy. Co-operating together, the worker walked backwards paying out the fibres as they were twisted into a yarn.

The length of the ropewalk determined the length of this yarn and so the length of the eventual ropes. [3] A number of such yarns were then fixed to the rotating wheel for twisting together to form a cord, rope or hawser. Again, this required the workers to walk the length of the ropewalk. Some ropes were made from yarns soaked in tar (which has to be at a temperature of at least 212oF) as a preservative. [4] In the pre-industrialised era, this method had remained unchanged for centuries. The ropeworks at the Historic Dockyard, Chatham, still makes ropes in that way today.

In looking for women workers in Scottish ropeworks I found the wages books for the Forth & Clyde Roperie Co., Ltd.’s works in Kirkcaldy. The 1939-56 lists name about 150 different women. Many were there for several years, migrating between the different departments (apart from the all-male mechanic’s section). Surnames suggest that relatives from the same families worked together. Some sections had a male supervisor.

Otherwise this was a predominantly female environment. Ropemaking covered the following processes: cropping and balling, spinning (the biggest department), twisting and laying, and hardening. Later descriptions were simplified to ‘Batching and preparing’, ‘Manilla mill’ and ‘Soft fibre mill’.

Employment conditions and unionisation

Unhealthy Work

The poorest social classes of workers, from which most of the employees were drawn, were already likely to be at the lower end of any life-expectancy statistics. Photos of 19th and early 20th century ropeworkers also show a marked contrast between the owners and managers and the stunted statures of the women and labouring male workers. Given that multiple generations of the same families were often working in the industry, the fact that at least 10% of the women could expect to develop ‘pousse’ – a respiratory disease similar to emphysema or byssinosis, probably contributed to inter-generational ill health.

Most girls starting in a ropeworks would apparently cough for a few weeks before acquiring a ‘tolerance’ to the clouds of dust. (It was hemp fibre particles mixed with agricultural dirt from the countries of origin such as the Philippines, Mexico and Chile). Nevertheless, they would most likely die of the pousse some 30 years later.

Organising

Probably most people interested in labour history will know of the London match girls’ strike of 1888. Their victory was considered an iconic turning point in the development of trades unions in the UK. However, quite early on, ropemaking, too, was also recognised as one of the ‘sweated’ women’s trades (meaning low-paid piecework with poor conditions)

Consequently ropemaking was also one of the first trades in which women became unionised. In 1889 suffragist and trade unionist Amie Hicks, née Cox, (1839-1917) set up the East London Women Ropeworkers’ Union.

Through that work Amie became a founder of the Women’s Trades Union Association that year. The Ropeworkers’ Union was one of the very earliest industry-specific unions for women. It continued until 1898. Amie was forewarned that she’d find ‘a rough, wild and even desperate class of women’. Instead she asserted that ropemakers were ‘very capable, independent sort of women [...] determined, self-respecting, and self-denying.’ [5]

Frost Brothers, 1890

The new union began supporting the women workers of one of the UK’s largest ropemakers, Frost Brothers, when they went on strike over low pay. This situation arose partly because the Thames shipbuilding industry had moved to Tyneside and Scotland. Demand for rope suppliers shifted north too. Frost Brothers was one of the leaders in the mechanisation of the ropemaking processes. If less skills and strength were needed, the firm thought it did not need to employ expensive men. The women struck for eleven weeks and attracted a lot of public attention to their cause. They exposed the terrible working conditions and very low pay. And their demands were met in full.

Liverpool, 1895

In 1895 a strike among women ropemakers in Liverpool led local unionising activist and dress reformer Mrs Jeannie Mole, née Fisher, (1841-1912) beginning her work with the women. Garnock and Bibby’s Ropeworks had decided to impose a wage cut of about 4 shillings a week (from an average wage of 9 shillings) on 35 female spinners. 100 women went out on strike. They won. The combination of the women’s confidence and Jeanie Mole’s support led to the employers being forced to rescind the pay cut and to improve safety in their ropeworks.

Later that same year women from another Liverpool ropeworks, Jacksons, struck when the firm not only cut the pay of one of their oldest members for time taken off. It also imposed a fine before she would be allowed to return to work. Jacksons tried to paint these women as lazy which resulted in a statement from Jeannie Mole that was quoted in the press:

“Do you know that many of these women rise before five, tidy their little homes, prepare the day’s food and pass the factory gates after a walk of two miles before the steam whistle stops shrieking at six thirty[...][then] most go on at driven work toiling until six. So many of them receive only a few shillings a week, and have to tramp a long way to reach cheap shelter, and are not able to afford out of their wages such nourishing food as would give them energy and vigour.” (Liverpool Labour Chronicle, October 1895)

The strike was almost immediately resolved in the women’s favour. A union was established and male ropeworkers also applied to join it. [6] The industry was to see more strikes from then on: by men objecting to women entering the trade, and by both women and men seeking better pay or working conditions.

London, 1913

In 1913 the Hoxton ropeworkers struck to object to the dismissal of an elderly worker. In all 100 women and 130 men downed tools. Their case was taken up by the Dockers Union. As a consequence the appalling sanitary conditions as well as pay rates became matters of public debate. The women’s average weekly pay in 1913 was 8s 5d (=£0.42. £62 today), as compared with the 13s (=£0.65. £96 today) a week required by the Alien Immigration Board as the minimum to ‘allow a woman to live decently in London. [7]

The timeline of significant strikes includes:

1856: male ropeworkers in Caithness

1866: Greenock

1871: Aberdeen

1911: Hull and Belfast

1913 and 1914: Tyneside

1913: Hoxton

1918: Belfast

1936: Belfast

1940, 48: Belfast

Facilities for the workers

However, some of the bigger ropeworks might go as far as Belfast Ropework Co. did and arrange social and sporting activities for their workers. The Belfast ropeworks was the largest in the world by 1939. Its own ladies football team began in 1931 and played charity matches against other local women’s teams. The team was said to have an aggressive playing style! However one of their colleagues was the Belfast May Queen that year.

Ropemaking today

Ropes used on most boats and ships today are made from artificial fibres, such as nylon or polypropylene. The post-WW2 transition to these materials saw a major change across the industry. Many small traditional works either closed or were bought up by large conglomerates such as British Ropes (later Bridon). Many job losses followed. The manufacture of steel wire ropes for stays, crane cables, hawsers etc has always been highly mechanised, with many high-risk processes. However women also work in this part of the industry.

The only ropeworks making ropes from natural fibres and also in a traditional ropewalk in the UK, is the Ropery at Chatham Historic Dockyard. Their commercial rope company, Master Ropemakers Ltd includes the world’s only woman master ropemaker, Leanne Clark.

Back to the exhibition home page.

- [1] Ahmad, E. 2023. Personal communication via Facebook. Isabel was her mother and she has given permission for this story and images of Isabel to be used.

- [2] Biddlecombe, G. 1848. The Art of Rigging, Norie & Wilson https://archive.org/details/artrigging00steegoog

- [3] Bryant, J. 1977. Ropewalks And Ropemakers Of Bristol. Bristol Industrial Archaeology Journal, vol 10, pp12-17. https://b-i-a-s.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/BIAS_Journal10_ROPEWALKS_AND_ROPEMAKERS.pdf

- [4] Chapman, Robert. 1869. A Treatise on Ropemaking as Practiced in Private and Public Ropeyards . H. C. Baird, Philadelphia. https://library.si.edu/digital-library/book/treatiseonropema00chap

- [5] Rees, Edward (2019). The East London Women Ropemakers’ Union: 1888-1898. A Case Study in Victorian Female Unionisation: ’Desperate Women’ and ’Irresponsible Advisers’? Student dissertation for The Open University module A826 MA History part 2.

- [6] Cowman, Krista (2004) '‘The workwomen of Liverpool are sadly in need of reform’: Women in Trade Unions, 1890–1914', Mrs Brown is a Man and a Brother: Women in Merseyside's Political Organisations 1890-1920 (Liverpool, 2004; online edn, Liverpool Scholarship Online, 20 June 2013), https://doi.org/10.5949/liverpool/9780853237389.003.0003.

- [7] Tchaykovsky, Barbara. The Ropemakers' Strike. Common Cause - Friday 19 September 1913, p6.