- Home

- Learn & Explore

- Discover

- Online Exhibitions

- Into the Ice: The Arctic Career of Captain Sir John Ross

Introduction

The end of the Napoleonic Wars saw Britain emerge as the de facto naval power in the world. However, victory had come at a cost, and the enviable Royal Navy had become a heavy burden on the finances of the state. In just two years, 130,000 serving officers and men was reduced to just 20,000; ninety ships of the line dropped to just thirteen. In the aftermath of the war, the value of the navy was called into question; exploration reared its head.

Sir John Barrow, 2nd Secretary of the Admiralty in 1804 would spend the next thirty years feverishly promoting the cause of British exploration around the world; notably the search for the fabled Northwest Passage. The search for this accolade would claim hundreds of lives and thousands of pounds.

Sir John Ross

John Ross, the son of a minister, was born in West Galloway on 24th June 1777, joining the ranks of the Royal Navy at the age of nine. Over the course of the Napoleonic Wars, Ross’s career saw him serve in the Mediterranean, West Indies, North Sea and the Baltic, with a brief secondment to the Swedish Navy. Severely wounded on multiple occasions, in 1806 he suffered both broken legs, a broken arm, a bayonet wound to the torso, and three sabre blows to the head. A capable intelligent man who attained the rank of commander without the aid of patronage, he was one of just a handful of the hundreds of commanders that was continuously employed throughout the latter stages of the war.

He was also prone to vanity, hungry for opportunity and known to be obstinate and short-tempered. William Edward Parry, who was to serve as second-in-command to Ross, was Barrow’s first choice, Ross’s military record winning out. The expedition would be Ross’s first official command.

“His Royal Highness the Prince Regent having signified his pleasure to Viscount Melville, that an attempt should be made to discover a Northern Passage by sea, from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean; We have, in consequence thereof, caused four ships or vessels to be fitted out and appropriated for that purpose, two of which, the Isabella and the Alexander, are intended to proceed together by the north-westward through Davis’ Strait; and two, the Dorothea and Trent, in a direction as due north as may be found practicable through the Spitsbergen seas.”

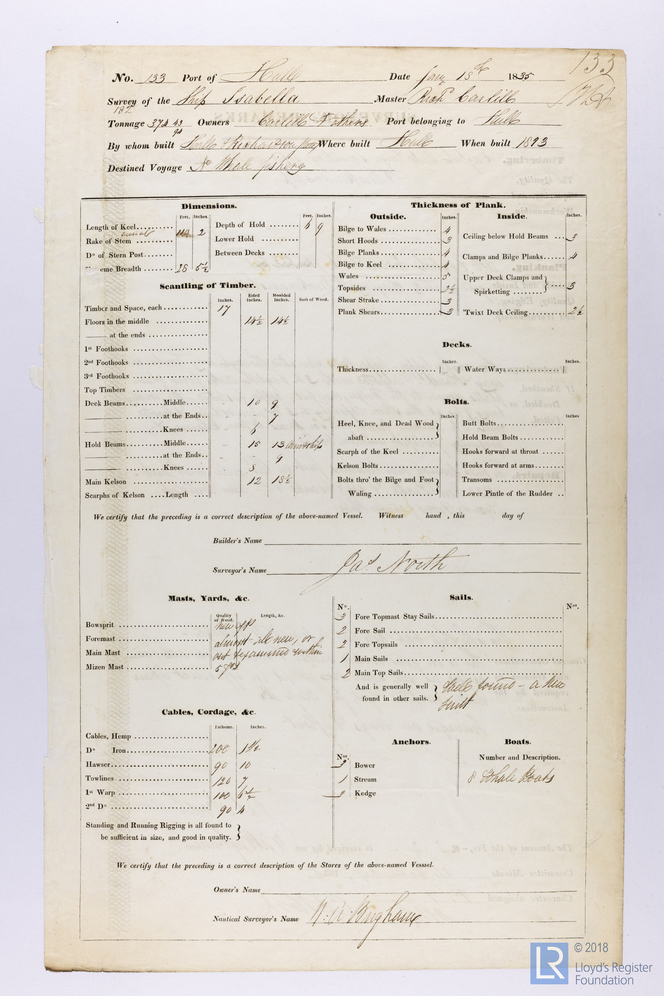

Isabella

Isabella, a former Hull-built merchant vessel of 385 old measurement tons, was purchased by the Admiralty along with the Alexander, and would be personally commanded by Ross. Parry, would take the Alexander. Together, both ships were sailed to Deptford in January 1818 and converted for the perils of Arctic service.

This included sharpening the bows, reinforcing her internal structure with quarter inch iron plating, doubling planks and ensuring an adequate supply of essentials; ice anchors, ice poles, saws, hand drills, canvas, 56,000 iron nails, and more than 3,000 extra feet of timber for any necessary repairs.

Crewed by experienced whalermen, the Admiralty offered all men double pay and issued them with fur blankets and warm winter clothing. Among the most prized possessions were a well-stocked library of reference books on Arctic science and exploration, an array of scientific instruments, luxury items to trade with, and nearly 130 gallons of gin and brandy!

All four ships departed together from the Thames on 25th April up the east coast to Lerwick. There the two expeditions parted ways, both bound for Arctic.

View full details

Voyage

One month later, off the southern tip of Greenland, Ross notes that the first icebergs were spotted by his western expedition.

On 3rd June the Isabella and Alexander crossed into the Arctic Circle and toasted the health of King George III in the shadow of the icebergs. The next few weeks were spent taking readings, recording atmospheric measurements and surveying the landscape:

“The water was glassy smooth, and the ships glided gently among the numberless masses if ice…”

Progressing north, Ross and Parry were greeted to the cheers and shouts of thirty whalers held up at the western Greenland shore, waiting for the ice to move. The expedition would spend the following month practicing ice cutting, harvesting whale meat, and checking their supplies and equipment before the passage opened.

Pushing on and leaving the whalers behind, Ross would name pass the mountainous area Melville Bay after the 1st Lord of the Admiralty. Progress slowed as the winds died down. On 7th August disaster nearly struck. Stuck in between hundreds of ice flows, the ships collided with each other causing considerable damage. Worse still, as the ice drifted apart, the bower anchors of both ships became locked, threatening to pull the other apart. Eventually, as the ice relented, the ships righted themselves, and the crews began to frantically begin the necessary repairs.

Three days later, after heavy repair work had been completed, the expedition halted once more; unknown figures were spotted waving from across the ice.

Arctic Highlanders

Ross immediately gave orders to secure the ships to the ice and rescue what he believed to be a group of shipwrecked sailors. Attempts proved impossible as the group withdrew on dog-drawn sledges whenever the crews drew nearer. It soon became apparent that they were indigenous to the region, the northernmost dwelling people on earth, the Inughuit.

For the next day Ross attempted to make contact with the group, but to no avail.

Appearing early the next day, John Sackheuse, the expedition’s indigenous interpreter ventured out to greet the group, quickly establishing that they spoke a recognisable dialect. The small band had journeyed south to hunt narwhals and believed the ships came to kill them.

Soon after Ross and Parry embarked across the ice in full dress uniform, Ross treating the meeting as a diplomatic visit. What was learned was that the group and their tribe had never had any contact with other human beings.

“…nor have they any tradition how they came to this spot, or from whence they came; having until the moment of our arrival, believed themselves to be the only inhabitants of the universe.”

The encounter was a peaceful and curious one. Ross’s detailed writings records exchanges of gifts, questions, sketches, displays of dancing and music (including from the ship’s crews), and the excitement caused by an encounter with a pig. Ross declared the region to be the Arctic Highlands, and the communities that lived there, the Arctic Highlanders.

It is now believed that the Inughuit had become separated from the other Greenlandic tribes around 1450, wandering north during the Little Ice Age.

A favourable southerly wind forced Ross to bid farewell and break off further contact.

Croker's Mountain

Venturing further, the expedition would explore Baffin’s Bay and pass into the Lancaster Sound, entering the waterway on 29th August. The Isabella, nine miles ahead of the Alexander, slowed her progress as she met a thick blanket of fog ahead. On the afternoon of 30th August, the fog lifted slightly, Ross declaring that the bottom of the bay formed a ‘chain of connecting mountains’ north and south. The fog cleared, Ross tacked Isabella about to catch up with Alexander, declared the path barred, sketched the mountain range and named them ‘Croker’s Mountains’, after the First Lord of the Admiralty. This decision would result in a controversy that dogged Ross for the rest of his career.

Parry and the senior officers of the Alexander would later claim that no land had been seen by them.

Arriving at Cumberland Sound by 1st October, a potential passage, Ross’s nerve failed him. The weather became noticeably colder and fearing the two ships may become trapped in the ice, Ross abandoned the expedition altogether and ordered the ships back home.

Controversy

Arriving at Lerwick, Ross sent a letter to the Admiralty informing them of his return and proclaiming Baffin Bay explored- no westward passage could be found here. Disembarking at Grimsby with his logs, journals and reports, he headed for the Admiralty and received word of a promotion to captain. His good fortune was short-lived.

Barrow was furious. Discrepancies existed in the accounts of the topography, rumours flew about the non-existence of ‘Croker’s Mountains’, and worse of all, it was believed that Ross had lost his nerve and returned too early.

To make matters worse, public accusations were made by Edward Sabine, Parry’s second-in-command aboard the Alexander that magnetic observations claimed by Ross were in fact taken by his nephew, James Clark Ross. The result was a formal public enquiry; an embarrassment to the Admiralty.

Things got worse. A newly sanctioned expedition under Ross’s former second-in-command, Parry, categorically disproved the existence of ‘Croker’s Mountains’ in 1819. Ross’s expedition had been a failure, his reputation was in tatters, and he would never again be employed by the Admiralty.

Disgrace and offer by Felix Booth

The 1820s would see the ascendancy of Captain Parry and his four Arctic voyages. Meanwhile, Captain Ross filled his time plotting a chance to clear his name. In 1828, he presented proposals to the Admiralty to lead a new expedition to the Arctic; this time by steamship. The steamship would be small, sparsely crewed, and would possess a shallow draught to ease navigation among the ice floes and enable the vessel to creep along the coastlines in search of the Northwest Passage. The Admiralty declined.

Undeterred, Ross reached out for private sponsorship. His searches proved fruitful and it was not long before he had secured a princely total of £10,000 from the charitable and wealthy gin magnate, Felix Booth. At age 52, Captain John Ross would once again sail to the Arctic.

Victory

With funds secured, Ross quickly purchased the small 85-ton steamer, Victory, for the price of £2,500. Her record can be seen in Lloyd’s Register of Ships.

An oak-built paddle steamer, she had previously operated as a mail packet between Liverpool and the Isle of Man. Ross swiftly set about making the necessary preparations for her voyage to the Arctic.

As well as reinforcing her internal structure a unique feature was installed to the Victory that allowed her paddlewheels to be lifted out of the water and clear of the ice. Additionally, to ration her coal stores, her sails could be used. In addition Ross had her engines removed entirely and replaced with a new powerful patent by Braithwaithe and Ericsson. With a stock of food for over a thousand days, news of Ross’s ambitious expedition by steam spread across Europe.

The Celebrity of Ross

A highly celebrated affair, Ross’s expedition, the first by steam, attracted visitors from across British and European high society. Ross was visited by several Lords of the Admiralty, as well as William Edward Parry, John Franklin, the Duke of Clarence, and notably the Louis Napoleon, the future King of France. Astonishingly, Ross was inundated with naval officers and seaman across Europe begging to be a part of the ship’s company. Barrow, noticeable by his absence remained obstinate in his criticism of Ross.

Departing London on 23rd May to cheering crowds, Ross and his nineteen-man crew pushed on to the Arctic, arriving in Greenland a few weeks later. Progress had been painfully slow; Victory’s engines constantly failed along the way, and she progressed primarily by sail alone. Their luck changed, however, in Greenland as they were met by an Arctic summer that was the warmest in living memory.

On 6th August 1829, Victory passed into the Lancaster Sound, the site of his humiliation ten years earlier, and he disappeared into the ice floes.

For the next four years, there would be no news of Ross or the Victory.

2nd Voyage

Ross’s voyage pushed on and headed south into Prince Regent Inlet. From there on, the party aimed to reach Fury Beach, the site where HMS Fury (and her precious ship’s stores) had been abandoned by Captain Parry’s second expedition in 1825. The tents left behind had been damaged by polar bears but the provisions; sugar, cocoa, canned meat and spirits, as well as serviceable sails were packed into Victory. These vital stores would keep the expedition provisioned for three years.

Pushing on, the Victory had claimed and named ‘Brentford Bay’ and the ‘Felix Boothia Peninsula’ in the name of the king. However, by September the weather turned and the ice began to hamper progress, forcing them to regularly take shelter.

With winter fast approaching, Ross looked for a secure place to anchor. He chose and named ‘Felix Harbour’, a point roughly 150 miles south of Parry’s furthest northerly point. A secure area was cut using the saws, the upper deck enclosed by canvas, and the topmasts removed. Interestingly, at this point Ross chose to remove Victory’s troublesome engines and paddles; she would be a sailing ship going forward. Various lookout points and an observatory were quickly set up, and a routine of religious services, daily exercise, and classes for mathematics, reading and writing became the order of the day for the next few months of the long Arctic winter.

Overland Expeditions and a Second Winter

By January 1830 the lookout at the observatory declared an that an armed indigenous group were approaching. Both Rosses met with them and friendly relations were quickly established with the trading of gifts, including that of a wooden leg crafted by the ship’s carpenter, to one of the indigenous group that had a lost a leg during a polar bear attack. John Ross would gain vital knowledge of the surrounding lands, and James Clark Ross would learn the valuable skills of travelling by dog-drawn sled.

The next few months would see the launching of a flurry of overland expeditions by James Clark Ross. In mid-May he would venture for a total of 23 days, venturing as far as ‘Victory Point’ on King William Land.

June saw attempts to try and free the ship from Felix Harbour. However, progress in the ice proved slow. By September John Ross informed the crew that they would spend yet another winter on the coast of Felix Boothia. By November they were secure in ‘Sheriff’s Harbour’, just 3 miles from last season’s anchorage.

Magnetic North Pole and the Abandonment of the Victory

The arrival of spring would once again see the resumption of overland expeditions. In mid-May the following year, James Clark Ross ventured once more for the western sea and headed north. On 1st June 1831, James Clark Ross reached the magnetic north pole, placing a cairn on its spot with a message and claiming it in the king’s name.

The glory of reaching the pole was soon overshadowed by the task of freeing Victory from her harbour. Though the ice had begun to drift, progress was once again slow. They would travel for a total of eleven miles before the bergs would force Ross to once again seek another secure anchorage at ‘Victory Harbour’; their home for yet another long winter.

1832 proved to be turning point for Ross as his expedition suffered from a string of tragedies. One crewmate had died, another blinded, many of the sled dogs had died, and one of Ross’s war wounds had begun to bleed again, a sure sign of onset scurvy. With provisions beginning to dwindle, and temperatures falling Ross decided it would be perilous to wait for the ice to break; they would have to abandon the Victory.

It was like parting with an old friend - Captain Sir John Ross

Journey to Fury Beach and Fourth Winter

Ross’s plan was to head back for Fury Beach where HMS Fury’s two lifeboats could be launched, sailed to Barrow Strait, and eventually into the paths of the whaling fleets. In case these boats proved irreparable the crew would have to drag Victory’s two boats, loaded with 2,000lbs of provisions across an incredible 300-mile journey.

The entire party would eventually reach Fury Beach on 1st July 1832, finding three serviceable boats. Provisions were collected and the party immediately set about building appropriate accommodation if needed for the winter. Constructed from timber and sails in just twenty-four hours, emerged ‘Somerset House’ a tent structure measuring 31ft by 16ft and 7ft high.

Three weeks later, Ross made an ill-fated attempt to make a break for Lancaster Sound. The decision was soon judged to be a mistake; the ice would not allow it. Retreating the 32 miles back to Fury Beach over the course of six days, Ross and his crew resigned themselves to their fourth winter; this time at ‘Somerset House.’

Salvation

By the end of April, Ross took the decision to abandon Somerset House, cross the sea ice to Batty Bay on foot, and head north. Hampered by heavy ice and strong gales the expedition crossed Prince Regent’s Inlet, Admiralty Inlet and reached the shores off Navy Board Inlet. There a lookout was posted watching for any sails on the horizon, ready to launch the boats and use their gunpowder stores to send signal smoke.

Spotting one ship, the crew desperately headed for her, but a strong wind blew her out of distance. Fearing they would have to turn back, their prayers were answered on 26th August 1833. Rowing for an hour toward a second sail on the horizon, they were eventually seen.

Asking what ship had come to their rescue, the reply was “the Isabella of Hull, once commanded by Captain Ross.” To the stunned crew of the Isabella, Captain John Ross, presumed dead for the past two years, introduced himself.

Ross the celebrity explorer

Ross and his crew finally stepped ashore in Kingston upon Hull on 18th October after four and a half years in the Arctic, and was an immediate international celebrity once more. In a flurry of cheering crowds, meetings with notable persons and bookings for upcoming public dinners, Ross and his nephew headed for the Admiralty for an audience with William IV.

Having captivated the world, Ross was soon awarded a knighthood, receiving honours from Prussia, Sweden, France, and Russia, as well as thousands of congratulatory letters from the British public.

Despite not having been a naval expedition, Ross was able to secure a payment of wages for his crew for the full four and a half years serving in the Arctic Circle. With the magnetic north pole claimed, land charted and scientific measurements taken, Ross’s reputation was secure. Serving as British Consul to Stockholm until 1846, Ross enjoyed his newfound notoriety.

However, the Arctic would beckon once more.

Franklin’s Expedition

In February 1845 Sir John Franklin was chosen, at the age of 59, to lead another final push for the Northwest Passage, the wish of the 82 year-old Second Lord of the Admiralty, Sir John Barrow before he retired. The two experienced explorer ex-bomb vessels HMS Erebus and HMS Terror were the ships of choice. Sir John Ross’s warnings to Franklin of the size and depth of both vessel’s draughts fell on deaf ears.

Franklin’s Expedition would build on the discoveries of the voyages of the previous thirty years and explore the uncharted regions of the North American Arctic to the southwest of Lancaster Sound. With provisions for three years, and a library of over 1,000 books, the two ships departed the Thames in the summer of 1845 and headed for the Arctic.

On 26th July 1845 the two ships were spotted by two whalers. This was the last time the two ships or their 133 strong crew were ever seen again, spawning one of the largest mysteries that is only now coming to light after over 170 years.

The search for Franklin

By 1847, Sir John Ross was convinced something had befallen Franklin. Rushing to the Admiralty with a detailed proposal for a rescue mission commanded by him, (with a plan to reach the North Pole thrown into the bargain). His plan was rejected; there was no cause to worry about Franklin. 1847 would see Ross campaign up and down high society for a rescue mission.

By 1848, with no news heard from Franklin, and crucially no sightings, the Admiralty began to worry. Sir John Barrow, aged 84, died. At a flurry of urgent meetings of the Arctic Council (pictured) plans were drawn up to rescue Franklin.

Between 1847 and 1859 over thirty separate rescue expeditions were launched from Britain, the United States and Russia to name but a few. The Admiralty alone would expend more than £675,000 in their efforts to find Franklin, and offer heavy reward for information.

Ross the aged explorer

Franklin, an outspoken critic of the Admiralty attracted the support of Captain Franklin’s wife, Lady Jane Franklin. Self-funded to the cost of £530, and with Lady Franklin’s support, he purchased a small schooner, the Felix.

With a small crew under Ross, the vessel’s master is listed as Thomas Abernathy, an experienced seafarer, naval gunner and polar explorer, present on over six expeditions, including Ross’s arduous second expedition from 1829-1833. That year, the expedition set out for the Arctic; Ross was aged 73.

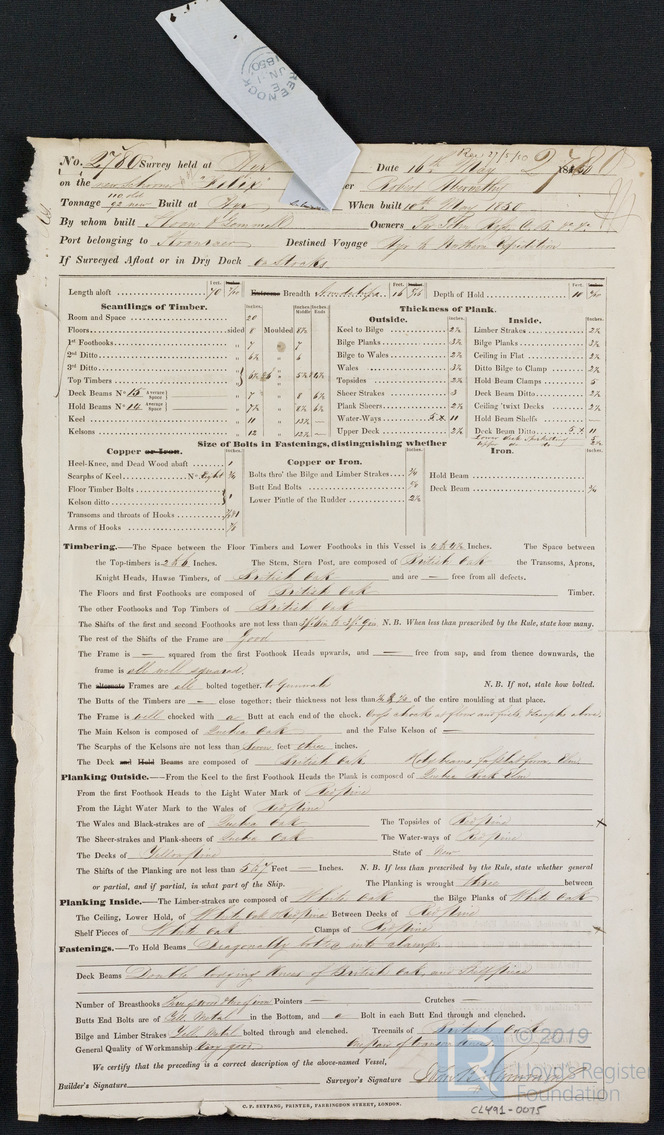

Felix

The keel of the Felix was laid down in March 1849 at Ayr by the shipbuilders Sloan and Gemmell. Measuring a total of 92 new tons and 70 feet in length, she was inspected prior to launch by Lloyd’s Register’s Surveyor, John B Cumming. Her survey report exists here, listing her owner as ‘Sir John Ross C.B. etc. etc.’ and her destined voyage as ‘Ayr to northern expedition.’

View full details

3rd Voyage to the Arctic and the death of Ross

Making speedy progress, Ross entered the Arctic Circle and met other ships off Cape York by the summer. The Felix, though well-built was not particularly robust and was under provisioned, forcing Ross to rely on other ships in the area for supplies and additional support.

Despite this, in August 1850, 1st signs of Franklin’s expedition were found on Beechey Island at the entrance to the Wellington Channel. Huge mound of tins, fire sites and debris. Crucially, three graves were discovered with headstones offering the name and dates of death.

Ross winters on Cornwallis Island, conducting overland searches and across the channel. During this time, Ross’s conversations with the indigenous communities of the region varied from not having seen any of Franklin’s expedition, to claims that they had been murdered. Ross believed them, another controversial decision when he arrived back home that would anger Lady Franklin in her fight to keep the efforts of relief and rescue alive.

With the ice thawing, and what he believed to be satisfactory proof of the fate of Franklin, Ross gave the order to head back to Britain in August 1851. This voyage would be the last time Captain Sir John Ross would go to sea; a career that spanned 65 years. During his expedition, Ross returned to the knowledge that he had been promoted to the rank of rear admiral. He would return to his estate in Stranraer for his retirement, though he would undertake facilitate negotiations with Sweden, Denmark and Russia on behalf of the British government.

Passing away on 30th August 1856, he is buried in London’s Kensal Cemetery. An impressive yet controversial career in polar exploration, Sir John Ross was a galvanising figure, stoic, intelligent and undoubtedly brave, others accused him of vanity and arrogance. Like so many others that had preceded and would follow him, he did not find the northwest passage, however his legacy and name lives on, scored into the maps of the Arctic.