Wednesday, November 22 2023

What is the Current Regulatory Landscape of Ship Safety?

The hierarchy of regulatory control of safety in ships is based on the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) regulated by the United Nations’ International Maritime Organization. This ensures international consistency and minimum safety standards for construction, equipment, and operation of ships. Safety standards are adopted and supervised through ship classification rules. Additionally, there are flag state and port safety marine control requirements. All these are supplemented by company specific owner and operator rules and requirements, all as explained by James Stride, ex-Royal Navy and now Head of Maritime Governance at Carnival UK. [1]

The Birth of SOLAS: Responding to the Titanic Disaster

The first SOLAS treaty was established in 1912 in response to the sinking of the RMS Titanic. [2] A further SOLAS treaty followed in 1929, and another in 1948 in the aftermath of the Second World War. Since 1952, SOLAS has been governed by the International Maritime Organization (IMO), under the auspices of the United Nations Organisation. [3]

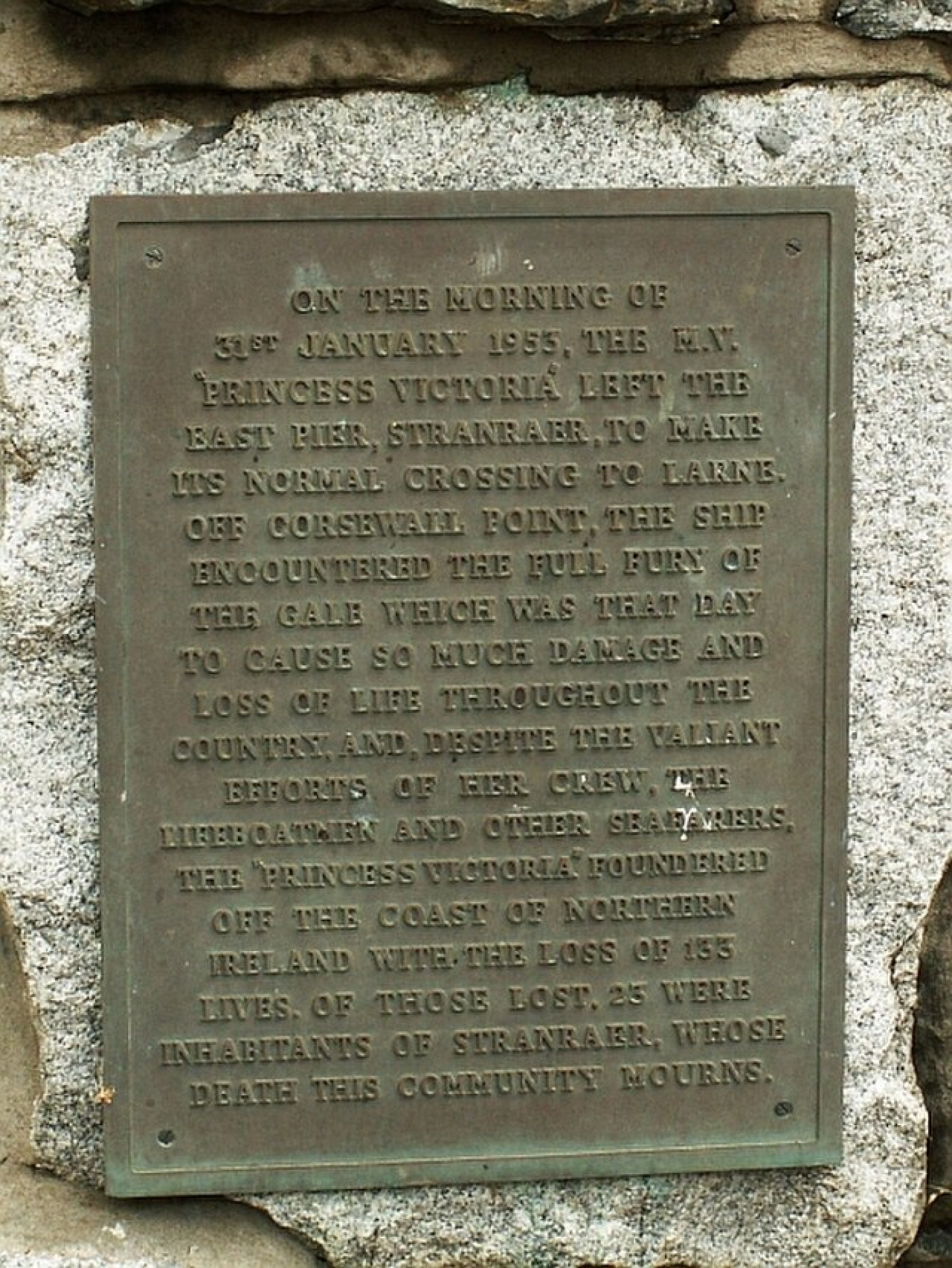

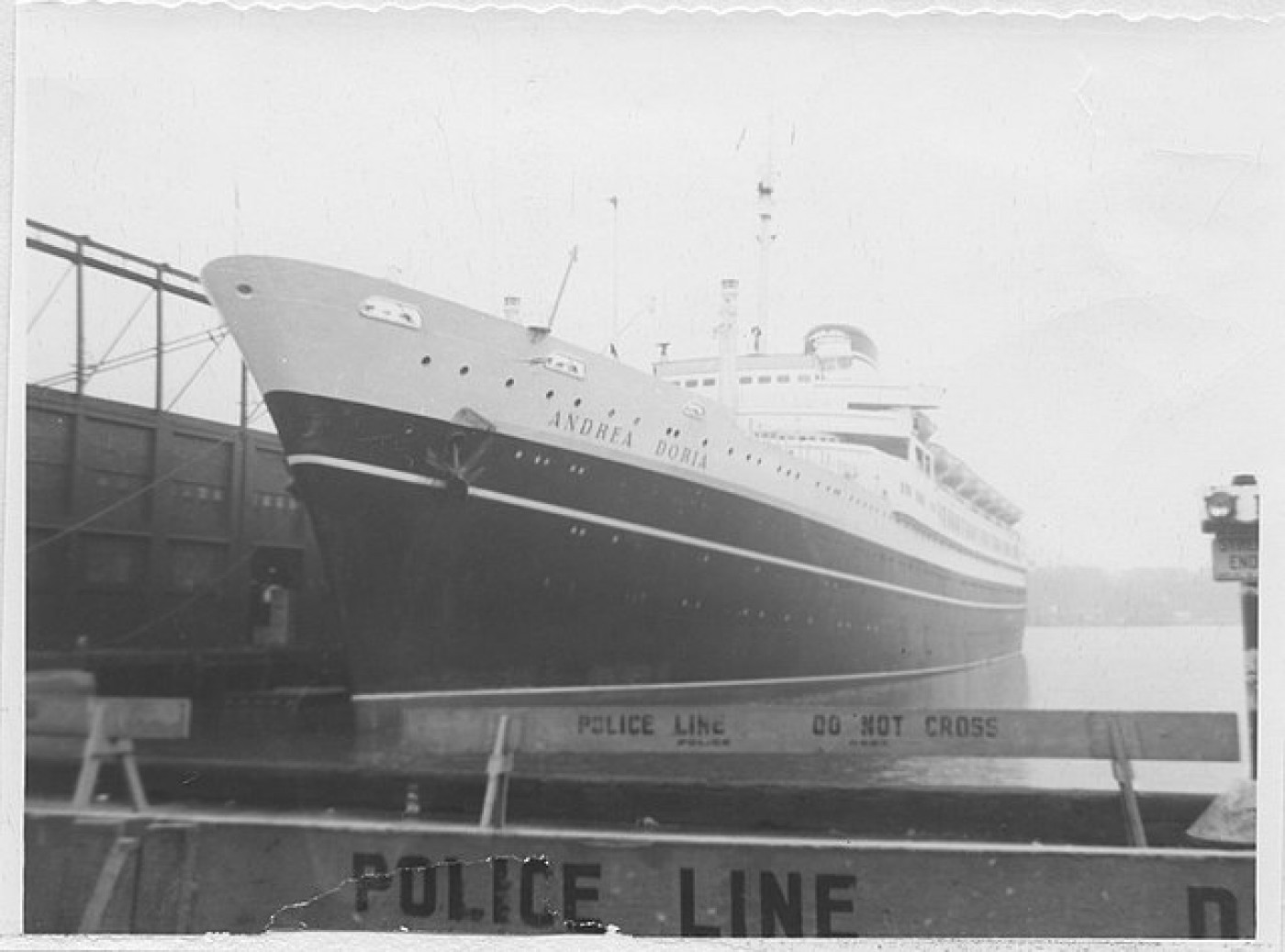

New SOLAS conventions followed in 1960 and 1974, after a period of maritime disasters with major loss of life including the sinking of the ferry Princess Victoria between Scotland and Ireland in 1953; the passenger liner Andrea Doria sinking off Nantucket in 1956 and the four-masted barque Pamir sinking off the Azores in 1957; the Lakonia cruise ship evacuated in the Atlantic Ocean with major loss of life in 1963; and the passenger cargo liner Royston Grange, lost after collision in South America in 1972. The 1974 Convention, still in force today, provided for amendments to SOLAS to be automatically adopted by default by signatories to the Convention. [4]

A commemorative plaque on MV Princess Victoria memorial in Agnew Park.

The passenger Andrea Doria the year that it sank, 1956.

The Impact of Cost Reduction on the Rate of Accidents

David Carter explains that a prevailing climate of cost reduction in commercial shipping through the 1970s and 1980s had reduced the resilience of safety systems leading to increased accident rates and consequent loss of customer confidence, which provoked further increase in maritime safety regulation through the 1980s and 1990s. [5] This led not only to low cost/low quality operations being regulated out of business, but also to a greater focus on human factors of maritime safety, alongside structural and regulatory factors.

Vaughan Pomeroy, a former Marine Technical Director of Lloyd’s Register, [6] explains that the Seafarers International Research Centre (SIRC) at Cardiff University discovered different perceptions of risk between grades of seafarer. They identified that junior grades often under-assessed the objectively higher rated risks (such as grounding), compared to the more ‘present’ risks of fire in which they had been regularly trained. This contrasted with how senior officers both onshore and afloat assessed risks, which has significant implications for how decisions at sea are made. [7]

James Stride explains that although the Royal Fleet Auxiliary (RFA) as a Merchant Navy service is subject to international and port marine safety requirements, Royal Navy (RN) operations, along with those of other military navies, are treated differently. However, since the 1980s, the RN and MN have drawn closer together regarding compliance with international safety standards.

Learning from the Herald of Free Enterprise, Scandinavian Star and Estonia Ferry Disasters

In the 1980s, the IMO Standards of Training, Certification and Watchkeeping (STCW) Code came into force to govern the training, assessment, and regulation of seafarer competences and to reduce inconsistencies of performance under the standards of individual flag states. [8] A paper by Schröder-Hinrichs et al. records that following the capsize of the roll-on/roll-off ferry Herald of Free Enterprise outside Zeebrugge harbour in 1987, “…the IMO started looking at human and organizational factors in a different light…”. [9] The 1990 Scandinavian Star ferry fire disaster on the seas between Norway and Denmark led in turn to increased regulatory focus on firefighting systems and layout design. [10] The 1994 Estonia ferry sinking in the Baltic, saw the greatest peacetime shipping loss of life in European waters and led to major changes in international safety regulations as well as in liferaft design.

MS Scandinavian Star in Lysekil harbour, Sweden, 7 April 1990.

The Life Saving Applications Code

The IMO introduced a new self-standing mandatory Life Saving Appliances (LSA) Code in 1996, completely replacing earlier requirements for LSA within SOLAS, [11] and the International Safety Management (ISM) Code was adopted by the IMO to provide consistency between flag states for the safe operation of ships, entering into force in 1998. [12] The RN also now adopts Whole Ship Safety Cases congruent with the ISM code, as explained by Vaughan Pomeroy. [13] This is elaborated in the next blogpost.

The next blog post looks at the historical context of Lloyd’s Register’s work with the Royal Navy, bringing RN and civilian maritime safety management into closer alignment.

- [1] Commander James Stride RN ret’d, conversation 06 March 2023. Stride was Commander Mobile Sea Training for the Royal Navy (RN) in 2015 and is now Head of Maritime Governance at Carnival UK, the owner of Cunard and P&O Cruises.

- [2] https://www.victoralexandrovicholersky.com/international-maritime-treaties-introducing-the-solas-convention/ Accessed 30 Oct 2022Accessed 22 March 2023.

- [3] https://www.imo.org/en/About/HistoryOfIMO/Pages/Default.aspx Accessed 22 Mar 2023.

- [4] The 1974 Convention, is usually referred to as ‘SOLAS 1974, as amended’.

- [5] David Carter, conversation as noted above. A shift to focus on quality rather than cost was the result.

- [6] V Pomeroy, ‘On Future Ship Safety – People, Complexity and Systems’, Journal of Marine Engineering & Technology 13, no. 2 (1 April 2014): 55–57, https://doi.org/10.1080/20464177.2014.11020298.

- [7] Seafarers International Research Centre at Cardiff University, see https://www.sirc.cf.ac.uk . Last accessed 07 May 2023.

- [8] https://www.edumaritime.net/stcw-code Last accessed 5 May 2023.

- [9] Jens-Uwe Schröder-Hinrichs et al., ‘Maritime Human Factors and IMO Policy’, Maritime Policy & Management 40, no. 3 (1 May 2013): 246, https://doi.org/10.1080/03088839.2013.782974. Accessed 09 November 2022.

- [10] James Stride, conversation as noted above. The Scandinavian Star fire revealed the spatial problems of dead-end corridors

- [11] https://www.imo.org/en/OurWork/Safety/Pages/historyofLSA-default.aspx Accessed 10 Feb 2023.

- [12] https://www.marineinsight.com/maritime-law/what-is-international-safety-management-code-or-ism-code-for-ships/ Accessed 26 December 2022

- [13] Vaughan Pomeroy, conversation 03 March 2023. Senior ship surveyor then Marine Technical Director of Lloyd's Register 1980-2020, subsequently Visiting Professor at Southampton University.