Tuesday, September 26 2023

Early Merchant Navy vs. Royal Navy Survival Equipment

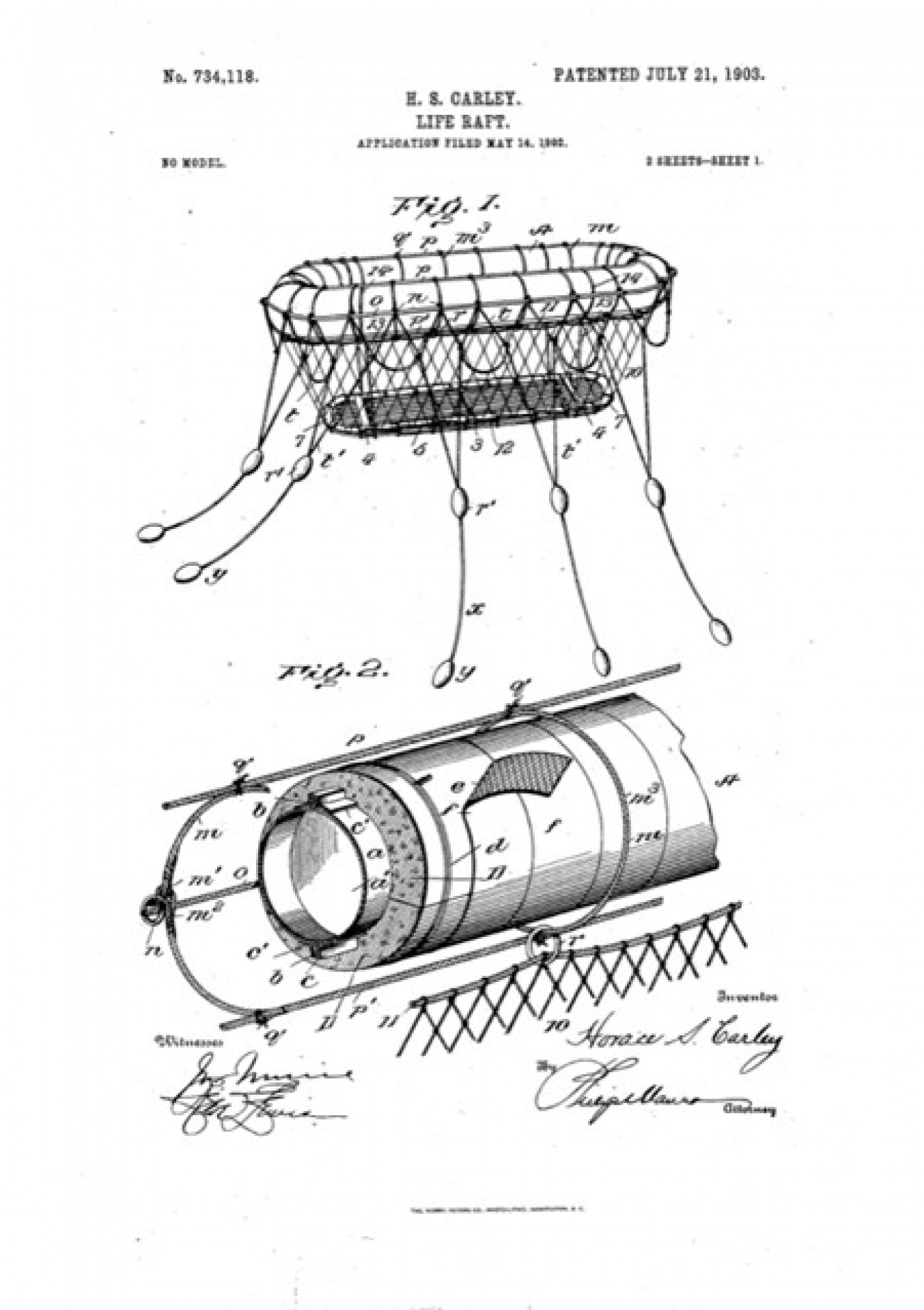

Many Royal Navy (RN) sailors died from ‘exposure’ in the Atlantic in the Second World War (WWII) despite having successfully escaped sinking ships and reached a ‘Carley float’ in the water. [1] These were a highly robust type of liferaft made of canvas-covered copper tubing and cork, which had been patented in 1903 and were the main survival equipment on RN warships in both World Wars. [2]

A history of life-saving appliances by Chris Brooks recounts that on the outbreak of war in 1939 RN sailors were not initially issued with personal flotation devices at all; personal intervention by Admiral Woodhouse led to the Admiralty re-issuing an outdated Admiralty Pattern No. 14124 inflatable rubber belt that had already been found unsatisfactory in the First World War, and which was subsequently condemned by the RN Personnel Research Committee. [3] Conversely, Merchant Navy (MN) ships in the Second World War typically only had a single motorboat with sufficient fuel for 60 miles, and carried open lifeboats equipped with oars and possibly a sail, which were often impossible to launch from rapidly sinking ships. Additionally, they carried bulky ‘Board of Trade’ cork personal flotation jackets taken up only when abandoning ship.[4] [5]

Illustration from 1903 US Patent 734118 for the Carley Life Raft

The Talbot Report: Identifying the Causes of Loss of Life at Sea

A seminal work on the effects of cold on survivors of shipwreck was presented in 1942 to the Royal College of Physicians, which provided evidence that most of the lives lost in both RN and MN in the early years of WWII were due to hypothermia (‘exposure’), rather than drowning. [6] Official guidance to improve survival at sea followed in 1943. [7] The Talbot Report in 1946 on the causes of loss of life at sea in the Battle of the Atlantic found that over 30,000 men died after abandoning ship and found the primary cause of death to be hypothermia during the survival phase. [8] It condemned the inadequacy of the Carley float, and of the basic inflatable lifebelts issued to RN personnel. [9] In consequence, the Royal Naval Personnel Research Committee, led by G W R Nicholl, carried out a series of experiments at the beginning of the 1950s with the University of Cambridge’s Department of Experimental Medicine, that tested new equipment for survival at sea to protect against hypothermia. [10] A 1953 film produced for the Physiological Society in the UK describing the work of Nicholl and his colleagues, shows the testing and development of a self-inflating raft with an enclosing ‘tent’. [11]

Evolution of Life Saving Equipment: Self-Inflating Liferafts and Inflatable Life-jackets

Further learning about the cause of deaths at sea in the Second World War was published in a 1956 Medical Research Council report by R A McCance and others. [12] This revealed that 70% of merchant ships sunk by enemy action went down within 15 minutes of being attacked, as noted by Max Hastings in his history of the epic 1942 Operation Pedestal convoy to deliver vital supplies to Malta.[13] Brooks’ comprehensive history of equipment to aid survival in cold water records that Nicholls and McCance’s work led to the introduction into general RN service of inflatable covered liferafts and the manually inflatable life-jacket, designed to be always worn in action and to float persons face-up. [14]

The significance of the inflatable life-jacket is that it can be worn comfortably at all times while working and in warfare action, whereas cork or kapok flotation appliances, as required by SOLAS to be carried on commercial vessels, are too bulky to be worn except when preparing to abandon ship, and present some hazard when jumping into water from height. [15] Brooks’ report also commends the very simple and compact RN issue ‘once-only’ survival suit to protect against hypothermia, designed to be carried together with a life-jacket in separate pouches around the waist. This is quickly put on over ordinary clothes and life-jacket and used in mass abandonment of ships where rafts and other rescue are immediately available. With only relatively minor improvements from the 1950s, these life-saving appliances were all used in action by RN, RFA and MN in the Falklands Conflict in 1982 and were similar to inflatable life-saving appliances in wide civilian use today. [16] The first self-inflating liferaft to be approved under the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) was produced commercially in 1965 by the British company RFD, now part of the Survitec plc group and similar RFD liferafts are still the main escape equipment on most RN ships. [17]

The next blog post in this series looks at the safety culture of the Royal Fleet Auxiliary and how post-war training with the Royal Navy has increased to partial integration of military and civilian competences by the mid-1990s.

- [1] Brian Lavery, Churchill’s Navy: The Ships, Men and Organisation, 1939-1945 (London: Conway Maritime Publishing, 2006), 104–5.

- [2] The Carley float https://patents.google.com/patent/US734118 Accessed 28 February 2023.

- [3] Dr Chris J. Brooks, ‘Survival in Cold Waters: Staying Alive’ (Ottowa, Canada: Transport Canada, Marine Safety Directorate, 2003), https://tc.canada.ca/en/marine-transportation/marine-safety/survival-cold-waters-2003-tp-13822-e.

- [4] D.L.S. Hood IWM107086 Engineer on RFA Cairndale in North Atlantic 1939-40, sank May 1941 and RFA Gray Ranger in North Sea and Arctic 1941-42, sank Sept 1943. Accessed 30 January 2023.

- [5] R.W. Crees IWM10717 Merchant navy apprentice on SS Paulus Potter sunk on Convoy PQ17 in the North Atlantic from Iceland to Russia. Accessed 30 January 2023. He recounts 8 days in an open lifeboat sailing to Novaya Zemla past the North Cape of Norway, suffering frostbite of feet permanently wet from being encased in rubber boots.

- [6] Macdonald Critchley, Shipwreck-Survivors: A Medical Study. (London: J&A Churchill, 1943). A published version of the Bradshaw Lecture 1942 delivered to the Royal College of Physicians.

- [7] MRC pamphlet, 'A guide to the preservation of life at sea after shipwreck' / Medical Research Council, Committee on the Care of Shipwrecked Personnel. London: H.M.S.O., 1943.

- [8] The Talbot Report of Naval Life-Saving Committee. London, 2 April, 1946.

- [9] https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/30090201 Accessed 23 Mar 2023.

- [10] George William Robert Nicholl, Survival at Sea: The Development, Operation, and Design of Inflatable Marine Lifesaving Equipment (London: Adlard Coles, 1960).

- [11] https://wellcomecollection.org/works/nmdhnakp Accessed 31 January 2023.

- [12] A. McCance et al., ‘The Hazards to Men in Ships Lost at Sea, 1940-44.’, Special Report Series (London: Medical Research Council, 1956), https://www.cabdirect.org/cabdirect/abstract/19572700766.

- [13] Sir Max Hastings, Operation Pedestal: The Fleet That Battled to Malta 1942 (London: HarperCollins, 2021), 164.

- [14] Dr Chris J. Brooks, ‘Survival in Cold Waters: Staying Alive’ (Ottowa, Canada: Transport Canada, Marine Safety Directorate, 2003), 46–54, https://tc.canada.ca/en/marine-transportation/marine-safety/survival-cold-waters-2003-tp-13822-e.

- [15] The SOLAS requirement for lifejackets to provide sufficient buoyancy to give 120mm of ‘freeboard’ to keep the mouth and nose above water was brought in by 1983 amendments; face-covering hoods on lifejackets to help avoid secondary drowning by inhalation of spray were introduced in more recent years.

- [16] See also a fascinating set of YouTube videos: British Mk 3 Naval General Service Lifejacket - 1982 ; British Pattern 5580 General Service Life Jackets; British 'Once Only' Survival Suit - 1960s to 1990s. Last Accessed 13 June 2023.

- [17] Survitec plc corporate history. https://survitecgroup.com/about-us/100-years-of-survitec/ Accessed 07 February 2023.